In this post, I will go through what accessibility is, why it matters, and explain some common accessibility issues.

What is accessibility

Accessibility might mean different things. First of all, it might be about the accessibility of the physical world. It relates to questions like “Is everyone able to reach a certain place, whether or not they use a wheelchair or a walking stick?” or “Is everyone able to find their way if they do not hear or see?”

Secondly, (web) accessibility is about designing and creating web services and sites that are accessible by all. Different types of disabilities can be permanent (e.g. blindness, deafness, physical disability), temporary (e.g. an injury, or after a medical procedure), or situational (e.g. needing captions on a video because you’re in a loud environment). Web accessibility might relate to questions like “Is everyone able to interact with a web page if they only use a keyboard to navigate?” or “Is everyone able to reach their goal on the page if they use a screen reader?” or “Does everyone have a good enough device to use the web page?” In this text, I’m focusing on web accessibility and will refer to it as accessibility.

Photo from Pexels by Kevin Ku

Why you should care

Accessibility makes it possible for people with different disabilities or disadvantages to use and interact with websites. The disabilities can be cognitive, physical, or sensory, and some of those disabilities might be visible and some are not. Different disabilities that should be taken into account are, to name a few, blindness, low vision, different types of colour blindness or other kinds of errors in vision, deafness, and various cognitive disabilities. Also, physical injuries should be considered; fine motor skills might be restricted or a keyboard might be the only way of interaction for someone. People with disabilities might or might not use different kinds of assistive technology. Disadvantages can be, for example, an old device or a slow internet connection. Crucial information should not be blocked by fancy features which don’t work on older browsers.

When all of those groups are considered, the amount of people who need or benefit from building accessible websites is not a small one. But on top of that, it is really everyone who benefits in the end. Accessible websites support different kinds of interaction methods, have clear user experiences, and have very few or no ambiguities. Users know what they can do, what kind of information is available, and how to proceed to achieve what they want.

Also, in many places, legislation already requires some pages to be accessible. In the future, probably even more domains are added to the accessibility requirement.

Some common issues

This list is by no means exhaustive and someone else could have picked different issues. In my opinion, these issues are quite common and that’s why I chose these.

Missing alternative texts

Every picture or icon should have a clear and understandable alternative text (WCAG 2.1 criterion for text alternatives). If the picture or icon is decorative, it needs to have an empty alt text attribute:

<img ... alt="" />

That way screen readers know to skip it. If there is no empty alt text attribute, screen readers will tell that there is an image but have no other information about it.

Poor contrast

Text on the web page needs to have a contrast of 4.5:1 compared to the background (WCAG 2.1 criterion for contrast minimum). Large text can have a contrast of only 3:1.

There are plenty of tools online to help you check the contrast between two colours. If the colour of the background varies, the contrast requirement needs to be met with all of the shades in the background.

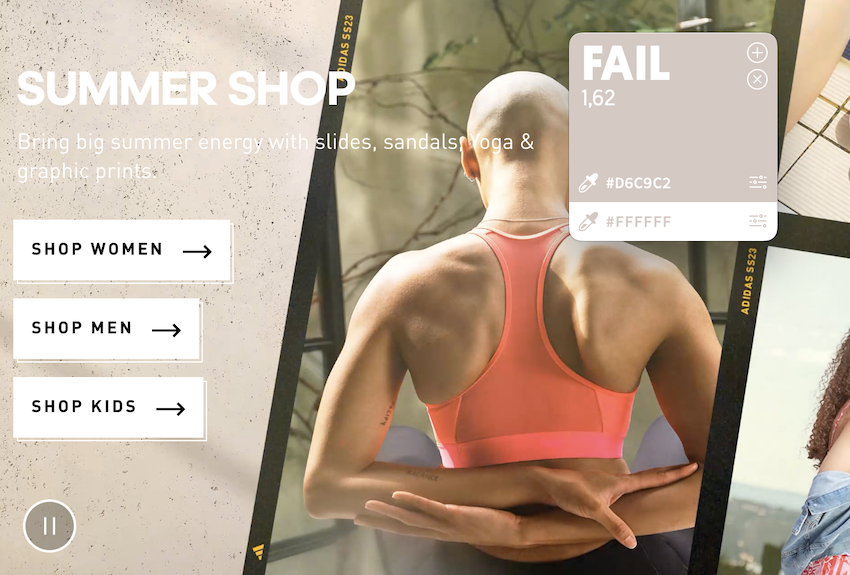

This screenshot is from adidas.com’s front page. The contrast between the concrete-looking background and the white text is only 1.62:1. (The contrast tool I am using is Contraste.)

Links without context

Many screen reader users might only go through the links on a page to find what they are looking for (WCAG 2.1 criterion for link context). So links with text like “here” or “read more” are of no use to them. Go where? Read more about what?

Link texts should always have the context with them. “Here” could be “Contact information” and “read more” could be “Privacy policy”. If an unclear link text is needed, an aria-label needs to be added.

<a href="..." aria-label="Read more about our privacy policy">

Read more

</a>

That way screen readers can provide the context for the user.

Inconsistent heading hierarchy

Screen reader users might also ask the screen reader to read out all level 2 headings. For that to be efficient, the heading levels and their order needs to be correct (WCAG technique for heading levels). For example, this is not okay:

<h1>Main title</h1>

<h2>Some heading</h2>

<h4>Wait what, where is level 3?</h4>

A web page should have one h1 heading. Other heading levels should come in order (e.g. h1 -> h2 -> h3 -> h3 -> h2 -> h3 -> h4). Same-level headings can follow each other (except for h1). There should never be any gaps in the heading levels (e.g. h1 -> h2 -> h5).

Missing form labels

Missing form labels are a nuisance to both users who can look at the web page and users who use a screen reader. All form components need to have a clear label (WCAG 2.1 criterion for labels or instructions and WCAG 2.1 criterion for name, role, and value).

Users should feel confident about what kind of information is asked of them. Labels should also indicate the data format if there are some restrictions or validation.

Lacking keyboard navigability and accessibility

Some users are only able to navigate web pages with their keyboard. Some choose to navigate in that way. All content on a web page should be reachable and operable with a keyboard (WCAG 2.1 criterion for keyboard use).

Pay extra attention to dropdowns, and hamburger menus. The latter might not be reachable at all without some fixes. Dropdowns might have a search functionality in them and that adds even more things to bear in mind when developing and testing them.

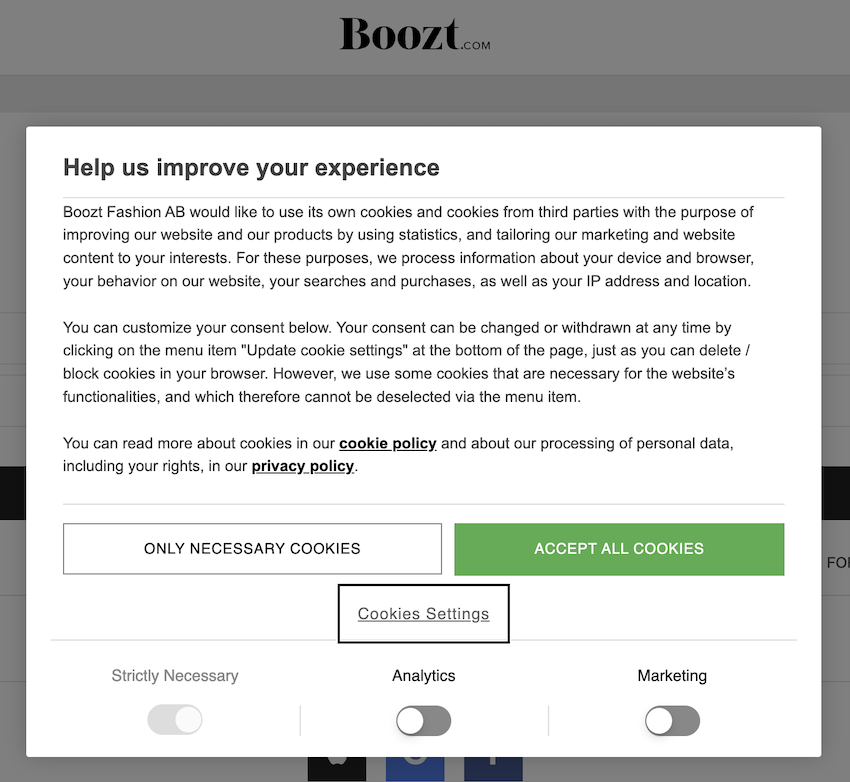

This screenshot is from boozt.com. I was using Voiceover on Mac as a screen reader and navigating with my keyboard. I wanted to click on the “Only necessary cookies” button. But that was not possible using only the keyboard. The keyboard focus moved from “Cookie policy” to “Privacy policy” (that’s what you’d expect). Then it jumped to “Analytics” (wat?). From there it went to “Marketing” and then finally “Cookie settings”. That was the end of the road. At no point were the “Only necessary cookies” or “Accept all cookies” active.

Automatic testing to the rescue?

Automatic accessibility testing can be a big help. It will help you find many basic errors. There are many tools for automatic testing, for example WAVE Evaluation Tool by WebAIM, Google Chrome’s Lighthouse, Pa11y, and aXe Devtools.

But you should bear in mind, that none of these tools will catch everything. And none of them understands the text on your page. There might be no semantic accessibility issues but they cannot check if the text content is understandable. People with cognitive disabilities require clear and to-the-point content on the page. They might be indifferent to inconsistent heading levels or missing alternative texts but vague or wordy texts can be a deal breaker.

My colleague Beata Kuśnierz wrote a great post last year about accessibility testing. Check that out, there are some great tips!

One thing to remember is that it is possible to build a perfectly accessible page (according to an automatic testing app) but in reality, the page is totally inaccessible. Manuel Matuzović has written a hilarious blog text about this.

Conclusion

After reading this, you should have a basic knowledge of what accessibility is and why it matters. You also have some understanding of what to be on the lookout for to tackle some of the common accessibility issues.

The internet is full of resources to help you. There are plenty of videos on YouTube to explain accessibility (I like Africa Kenyah’s videos, for example Intro to Web Accessibility for Web Developers). There are also lots of blog posts and articles to help you.

Some links to documentations or resources

- Basic stuff explained: Web accessibility in Wikipedia

- MDN’s A11y documentation

- Information about HTML elements and attributes: MDN’s HTML documentation

- Information about Accessible Rich Internet Applications (ARIA): MDN’s ARIA documentation

- A11y collective’s courses and trainings

- WebAIM’s color contrast checker

- WCAG 2.1 guidelines