Some time ago I wrote a short blog on upcoming changes to Java version 9. Link got posted to Reddit and caused some interest and also feedback and questions. Since then, some things have changed - and page that I used as source is now marked as obsolete - and there is also some new stuff to absorb. So I feel it’s time to go deeper into module system.

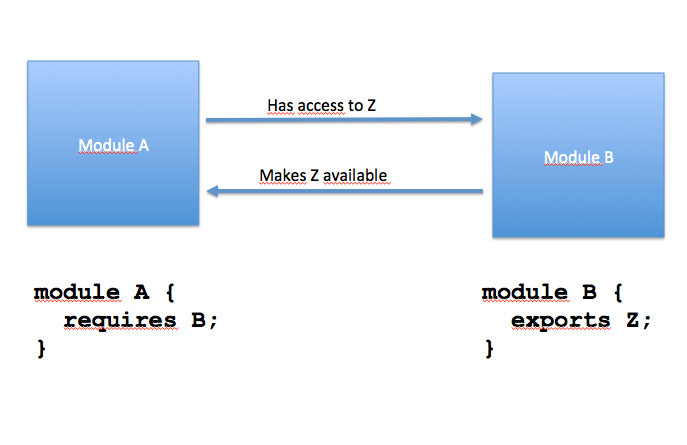

Short recap of what was mentioned last time: Java 9 will move on to definining new module descriptors, called module-info.java. These files can and will be used to define a few things: Name of the module that is being created, any packages the module will make available for others to use, and any requirements and references this module has for other modules. So for example:

module first {

exports my.package;

}

module second {

requires first;

}

So we have declared a dependency across the modules and packages. Second module is requiring everything that first package makes available - which is just a single package in this case. Anything else is encapsulated, hidden and not made available.

Unlike the information said when I wrote the first article, you cannot do version numbers here. Module system and syntax are not version-aware, there is just the dependencies. The tools layer does deal with version numbers, however, but module syntax does not.

Now here is the part where we can take this deeper. How do you work with these files? How does this let us say goodbye to classpath? How can you prepare what what comes late next year? What happens to all those jar files that are not module-aware?

Classpath goes bye-bye

Until Java 9, when your application uses third party libraries, or Java EE extensions, they needed to declare the classpath. Classpath means search path where any classfiles, or jar packages are found and loaded. When you run with classpath, you might see something like this:

java -cp lib/annotations-api.jar:lib/catalina-ant.jar:lib/catalina.jar org.apache.catalina.startup.Bootstrap

This has been much simplified to save screen estate: In real life for example application servers might load dozens of .jar files. It’s such a pain that they use a lot of scripts to process this classpath, for example: Grab everything in lib folder. Problem with this approach is that it’s a delicate mess. It breaks very easily, and it just flat out adds a lot of stuff to classpath without any encapsulation of internals, or any knowledge of real dependencies between these libraries. Basically dependency chart could go from any jar package to any other jar package - and back.

So how do the modules help? Well it all starts with these module-info files. They declare dependencies and declare what gets exported. Anything that’s not exported, is basically not available, it’s encapsulated. So this gives us the first benefit. Let’s do the simplest example with above module descriptions. We have:

- src/first/module-info.java

- src/first/my/package/Greeter.java

- src/second/module-info.java

- src/second/foopack/Main.java

You can probably guess the contents: Main depends on Greeter class, it will import it and call its methods. We can actually try this by compiling and running the code:

javac -d build -modulesourcepath src $(find src -name "*.java")

This will cause compiler to find all the sourcecode, and compile it under ‘build’ folder. It will end in similar folder structure, with module name coming first, and inside module folder we have the package folder(s).

Time to package the stuff:

jar --create --file mlib/second@1.0.jar --module-version 1.0 -C build/second .

jar --create --file mlib/first@1.0.jar --module-version 1.0 --main-class foopack.Main -C build/first .

These commands are pretty obvious, but you can see the versioning scheme going on here. We end up having two .jar files, with one of them containing information on what is the main class to run. So let’s run it. This is where it gets interesting:

java -mp mlib -m first

Yup, instead of listing every .jar file blindly if a flat clump of dependency hell, we name the module to run - module contains knowledge of main class, and the module path. So we’re set to go, anything else is already taken care of. No matter if you add 100 more .jar files - command still remains the same. Here’s the module path, please run this module.

And here’s where it gets really interesting. You can also link the modules together with a new tool, like this:

jlink --modulepath $JAVA_HOME/jmods:mlib --addmods first --output first

cd first/bin

./java -listmods

./module1

What happened? Well you linked the modules together, along with minimal java runtime. You can now run the application in a very simple fashion. You can also list the modules that are in module path.

Currently it is a bit unclear how cross-platform nature of Java will work, whether this jlinked app is portable or needs to be linked again on each platform. Would be relatively fast to just try it out but I’m happy to wait and see how it evolves. It’s clearly a work in progress but promising…

Services

A new part of Jigsaw spec defines concept of services - which is defined as loose coupling between service consumers modules and service providers modules. Idea is that module-info file is able to define implementation for provider API, like this (example from jigsaw quickstart):

module org.fastsocket {

requires com.socket;

provides com.socket.spi.NetworkSocketProvider

with org.fastsocket.FastNetworkSocketProvider;

}

So what does this mean? We have API, NetworkSocketProvider, and implementation, FastNetworkSockerProvider. And somewhere we have code that uses this declared NetworkSocketProvider, and is able to access any registered providers without naming them, like this:

public abstract class NetworkSocket implements Closeable {

protected NetworkSocket() { }

public static NetworkSocket open() {

ServiceLoader<NetworkSocketProvider> sl

= ServiceLoader.load(NetworkSocketProvider.class);

Iterator<NetworkSocketProvider> iter = sl.iterator();

if (!iter.hasNext())

throw new RuntimeException("No service providers found!");

NetworkSocketProvider provider = iter.next();

return provider.openNetworkSocket();

}

}

So you can see how the code is not aware of which implementation to use, but it will pick the first one that is found. And this decision is made in module-info file, outside the code.

Services are relatively new feature in Jigsaw, so again may easily change from what’s shown here, but on conceptual level it’s worth understanding what’s the idea and goal here.

Pitfalls and breaking changes

There is a way to start preparing for Jigsaw immediately: You get a tool with JDK 8 called jdeps. jdeps tool will analyze your dependencies and tell you if you are using hidden internals that will not be exposed in Java 9. You can use it like this:

jdeps -jdkinternals my.example.jar

So if your example jar package depends on jdk internals that will be encapsulated in Java 9, hidden, and not available, you’ll get them listed here. Then it would be time to start planning how to get rid of those. For some of them, you already have options. For others, JDK team will be bulding exposed APIs in the future. Note that this also holds for any third party libraries you are using.

Other thing to worry about is the fact that resource references inside .jar package are going to change. So if you’re pulling any images or config files from inside .jar package with ClassLoader.getSystemResource, and you had references like these:

jar:file:<path-to-jar>!<path-to-file-in-jar>

… then they are going to all change to something like this:

jrt:/<module-name>/<path-to-file-in-module>

Also, if you used endorsed override mechanism, or had any tools that used rt.jar or tools.jar libraries, they will not work in Java 9 without changes. We’ll see how fast IDE vendors and tools like Maven and Gradle will catch up with drastic changes here. Hint: Not yet.

There’s also some good news. Code that doesn’t use module system, is in ‘anonymous package’ - which means it will be able to see everything, and everything in it will be exposed. So if your third party libraries are not getting updated, you can still keep on using them. Also, you can freely combine old classpath with new module system, like this:

java -mp mlib -cp libs/*.jar -m first

Finally, the versioning system has changed, so while initially module-info would accept version number syntax, it doesn’t do that anymore. There’s a place for version numbers in the tooling, the module-version parameter you saw in previous examples. However also this versioning system is still under state of transition, and it remains to be seen how other dependency systems such as Maven, Gradle, OSGI, will handle it/work with it.

Conclusion

Jigsaw seems exciting, and it’s definitely a bold strategic move to keep Java alive for years to come. Schedule was recently revised, so you can expect feature complete status next year, and general availability release in 2017 - wow!

When it is released, it will bring obvious pain. That pain comes from changes that need to be done and new understanding that will need to be built. On the other hand it will also bring benefits that will last a long time, and again it’s something that just finally needs to be done. It’s still a moving target so many changes might be done to how it all works. Best thing to do right now is to follow this topic, and prepare for what’s to come. You have already taken a step reading this article, and remember that Jigsaw early access release is up for grabs and easy to use for testing already, jdeps tool is already part of Java 8 so you have it even without Jigsaw.

So, as always, here are a few links that relate to this article and are pretty recent (and correct at this point:

- [State of the module system] (http://openjdk.java.net/projects/jigsaw/spec/sotms/)

- [Jigsaw quickstart (new version)] (http://openjdk.java.net/projects/jigsaw/quick-start)