We’ve been developing and maintaining a Java Spring Boot codebase for the past 15+ years. In the beginning, there was one server (let’s call it Foo) and a client UI application. Over the years, this codebase has evolved into a monorepo containing four client UI applications and two server applications (Foo and Bar), all of which share the same database schema.

When Bar was introduced, a decision was made to share code (Spring components) directly from the Foo codebase. Even worse, Bar was directly coupled to Foo database schema. Now the older Foo application is finally near end-of-life and it should be replaced by a new application. However, with Bar directly dependent on Foo’s code and database, the question was: how do we achieve this replacement without breaking everything? To make matters worse, all applications are critical with 24/7 on-call support.

In this post I’ll dive deep into how our team tackled the challenge in decoupling the applications by systematic refactoring. As the work is still ongoing, I’ll focus on changes related to a single business domain. I’ll share lessons learned on managing risk, verifying quality, and keeping developer morale high while making large-scale changes to a critical system.

Here, There, Everywhere

Our initial task was to identify how the business domain (which we’ll call “Product” throughout this post), conceptually owned by the Foo application, was being utilized within Bar. What we quickly uncovered was a sprawling mess: a multitude of Product-related domain objects, DTOs, JPA repositories, Hibernate DAOs, named queries, and various other data access mechanisms, all scattered across both Foo and Bar, accumulated over years of development.

Whenever the Bar application needed to interact with “Product,” it seemingly randomly selected one of these services, repositories, or DAOs. There were no clear boundaries, no separation of concerns, and no unified interfaces. We were looking at hundreds of integration ‘seams’ where the Product entity was accessed, either directly in code or through database queries. Crucially, the Product entity’s influence wasn’t confined to the data access layer; its database identifiers and related logic were pervasive throughout the codebase.

To navigate this complexity, static analysis tools within our preferred editor, IntelliJ IDEA (specifically ‘Find Usages’ of classes and methods, and dependency graphs), proved invaluable. Our ultimate goal was to transition Bar to consume a dedicated ProductAPI, exposed as a new HTTP REST service for all Product information access. But how could we get there? The chasm between our current state and that desired future seemed insurmountable.

Our Strategy: Branch by Abstraction

Martin Fowler defines the Branch by Abstraction pattern as:

…a technique for making a large-scale change to a software system in gradual way that allows you to release the system regularly while the change is still in-progress.

It is especially powerful in critical systems when we must release changes gradually, ensuring the quality of the overall system and allowing multiple implementations to coexist simultaneously in production.

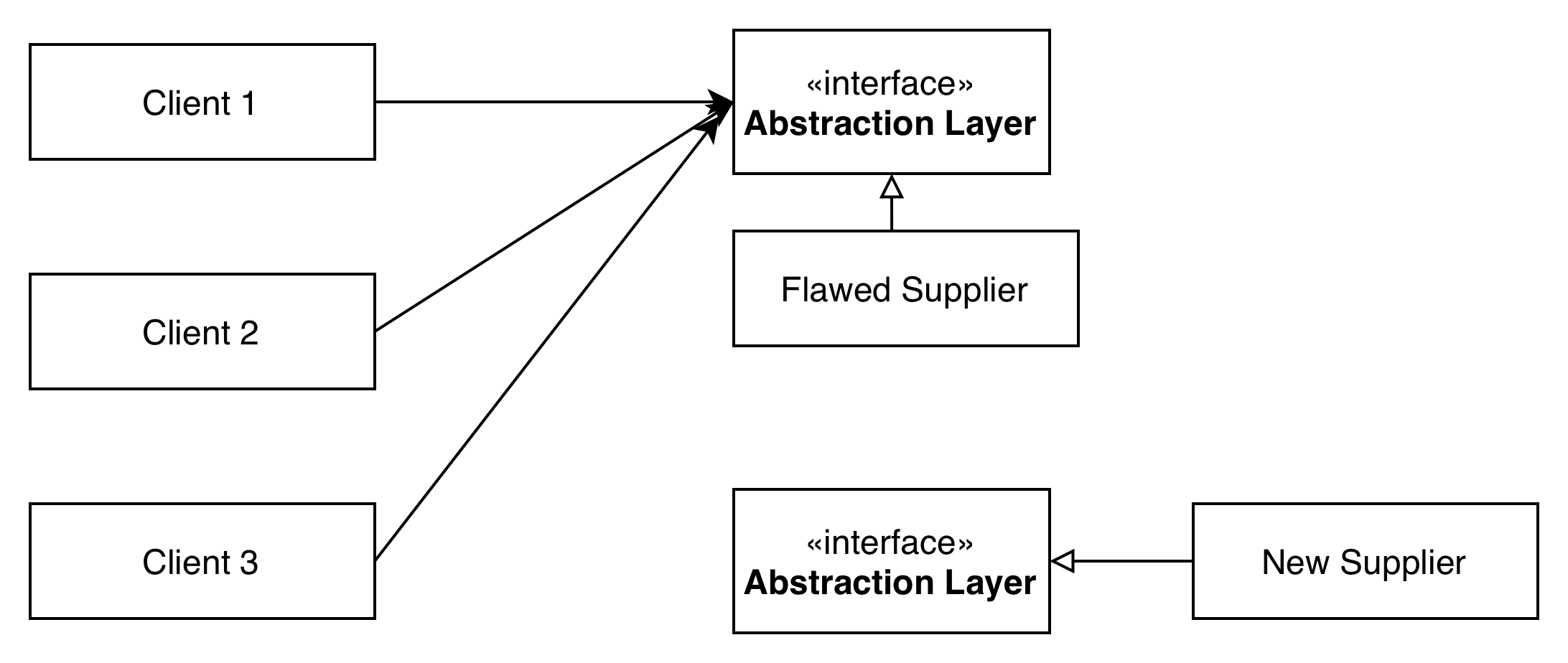

Here’s how Branch by Abstraction typically unfolds through its core phases:

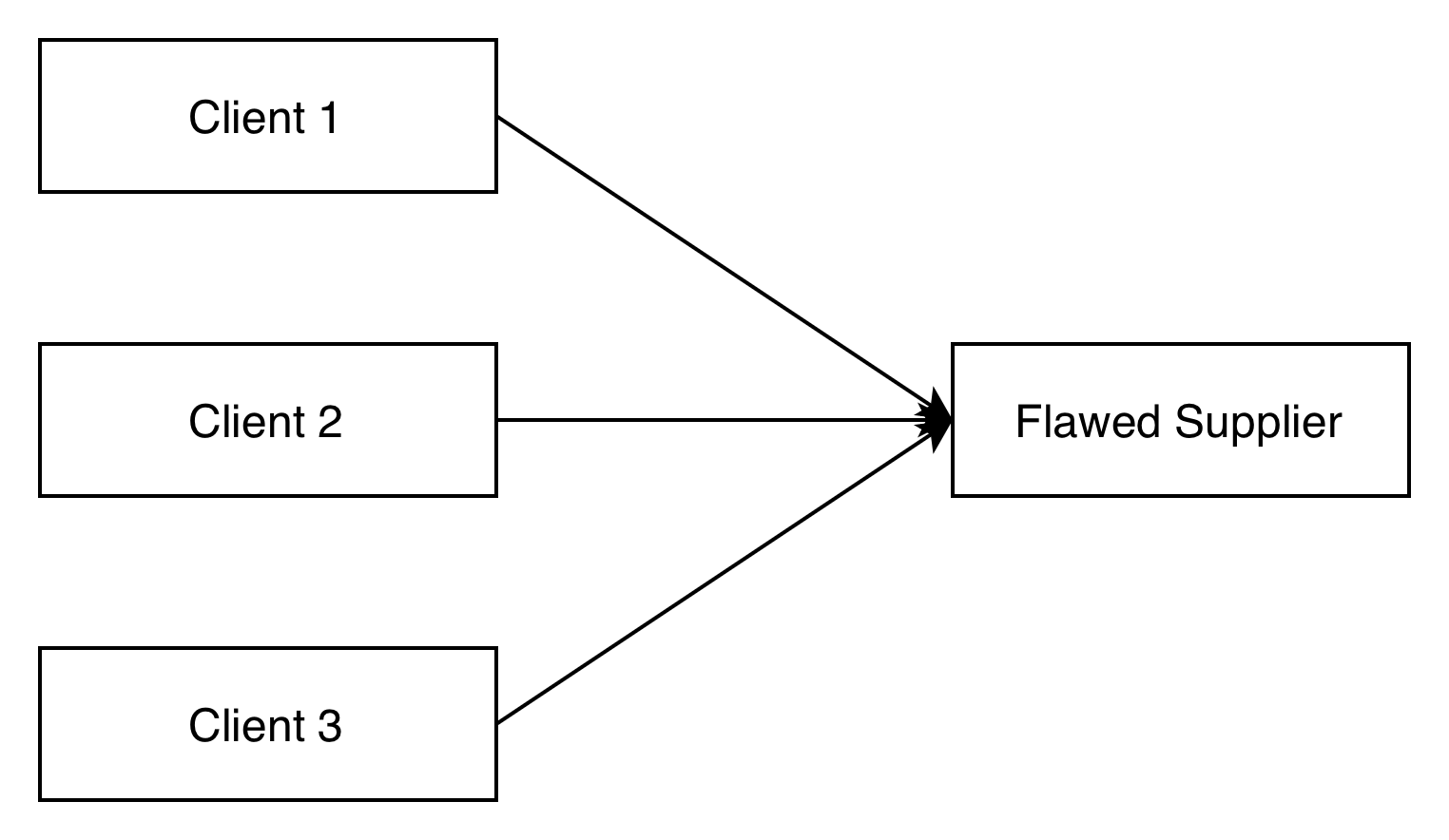

Phase 1: The Starting Point

At the starting point, we have clients calling a poorly behaving supplier:

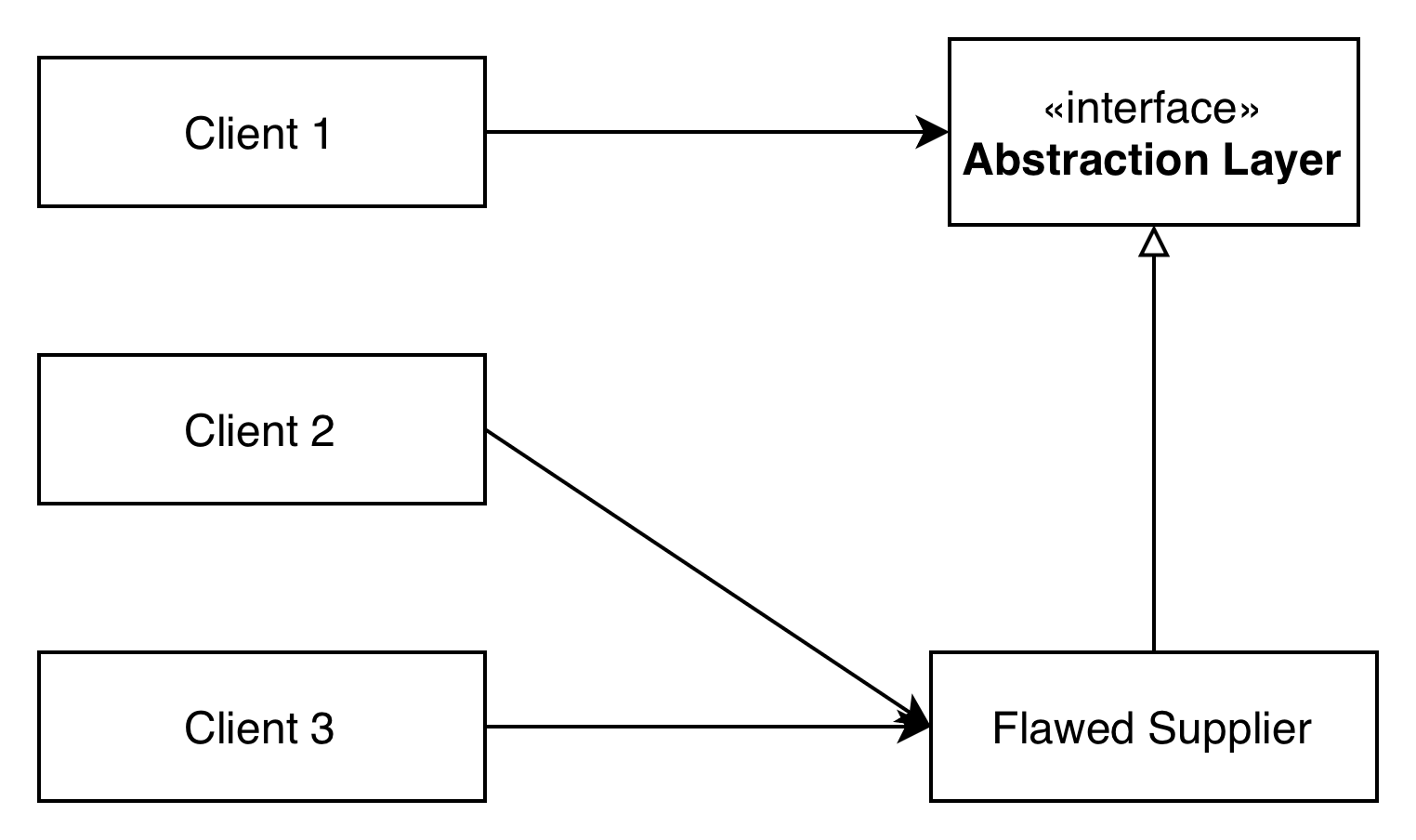

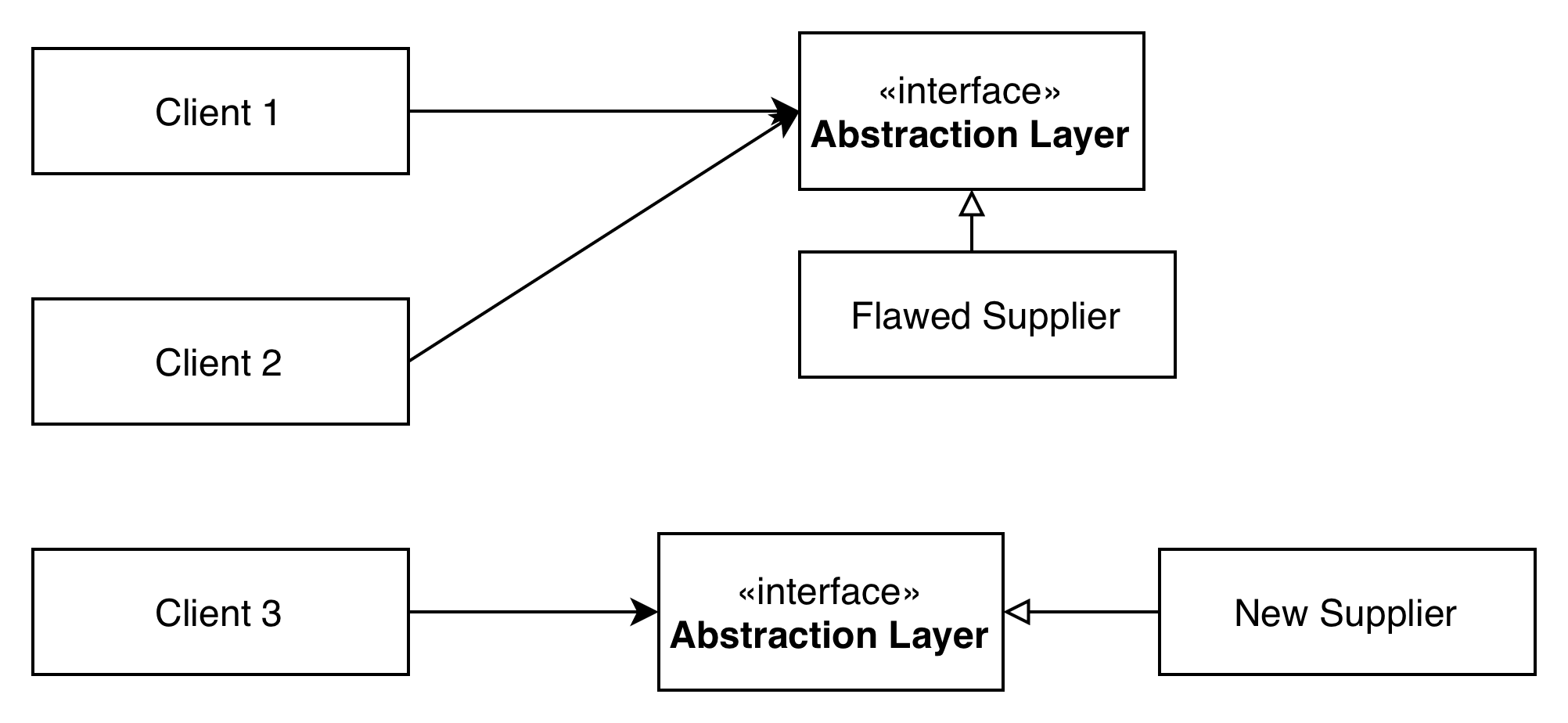

Phase 2: Introducing the Abstraction and Gradual Migration

We introduce a new abstraction layer (an interface) between the client and the existing supplier. We then gradually migrate client calls to go through this abstraction layer, piece by piece:

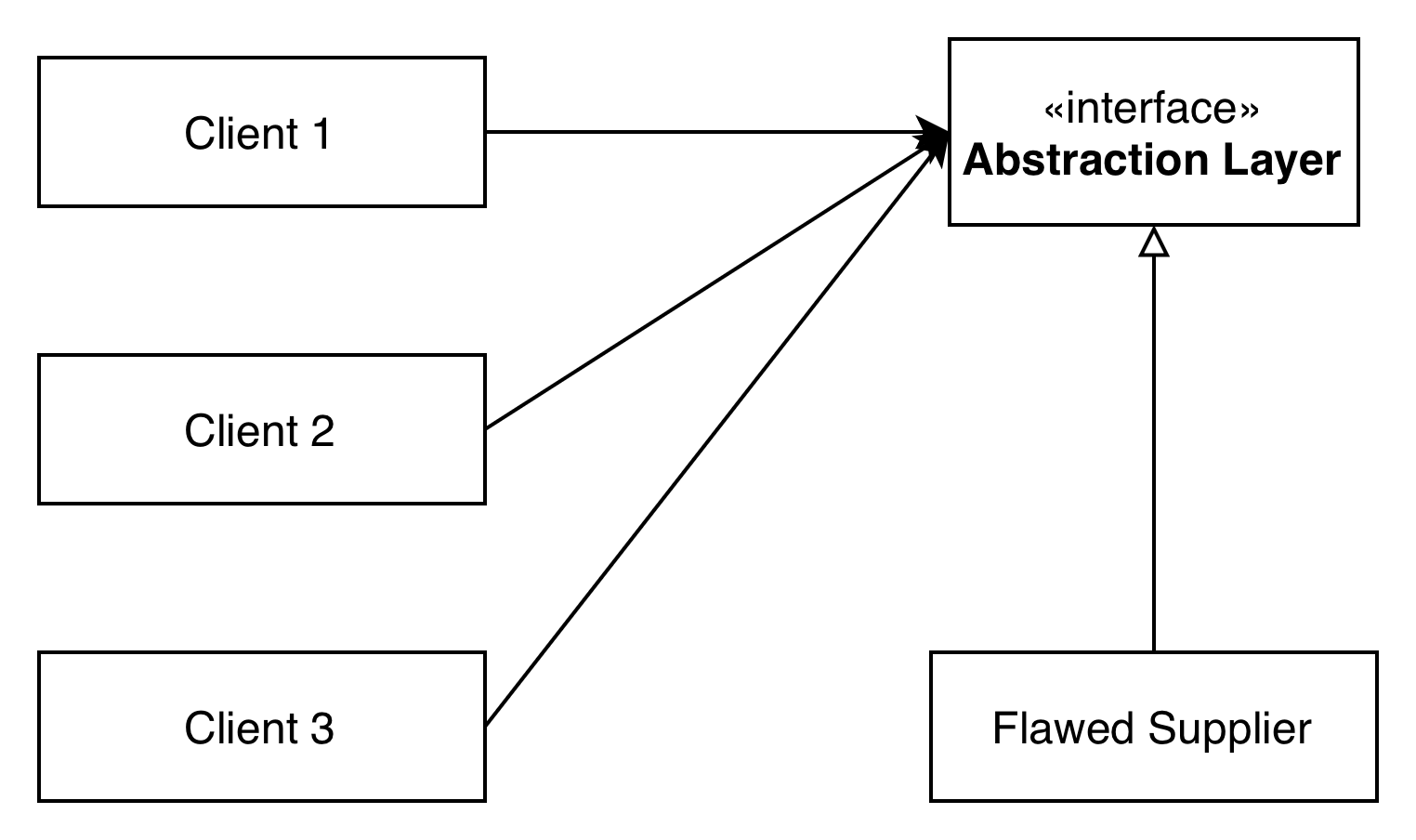

Phase 3: Full Abstraction Adoption

Eventually, all client calls have been successfully migrated to go through the abstraction layer:

Phase 4: Building the New Supplier

Next, we build the new, modern supplier, ensuring it fully implements the newly introduced abstraction layer:

Phase 5: Gradual Cutover to the New Supplier

We then start gradually switching clients to use the new supplier’s implementation of the abstraction. This critical phase can often be managed with feature flags or A/B testing:

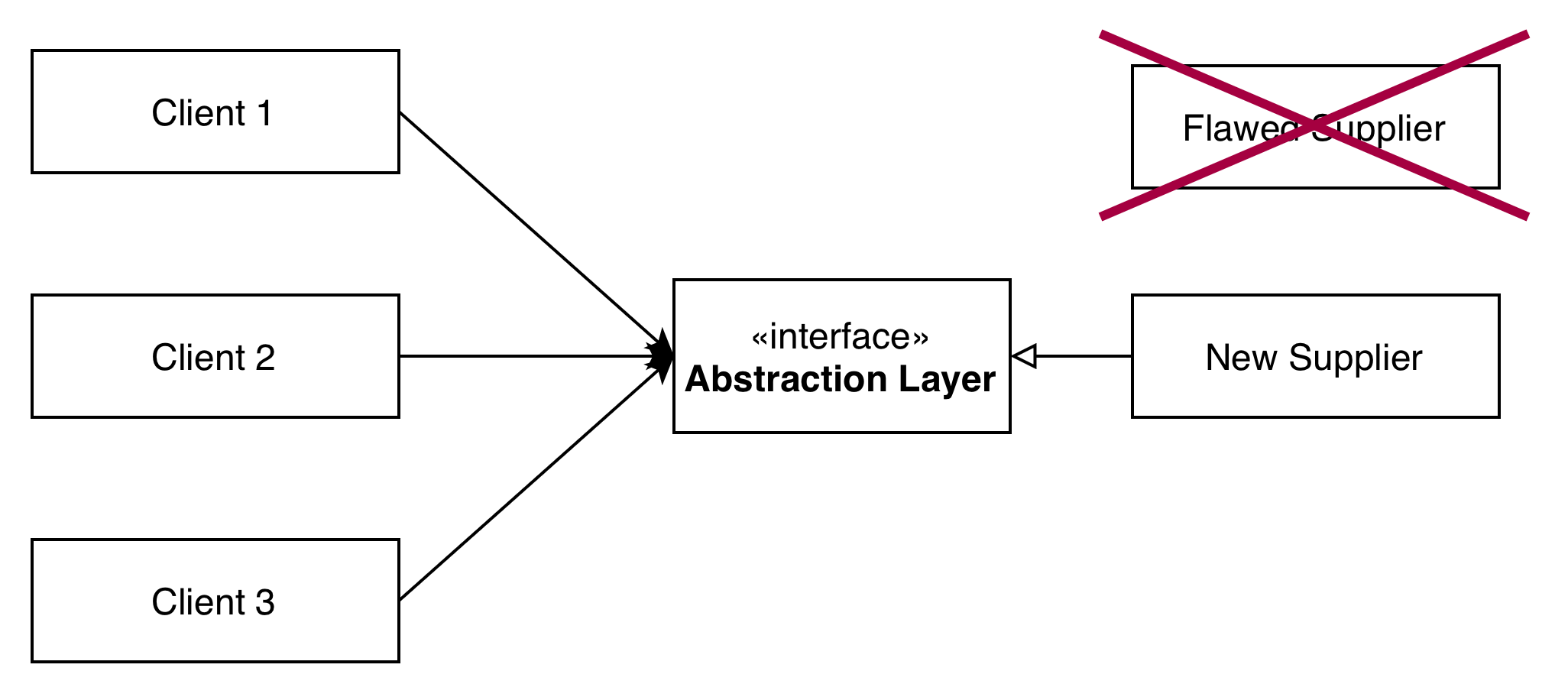

Phase 6: Removing the Old Supplier

Once all clients have been migrated to use the new supplier, the old, poorly behaving supplier (and its implementation behind the abstraction) can be safely removed:

In the intricate dance of large-scale refactorings, a core challenge lies in balancing delivery speed against the inherent risks of downtime and critical bugs. Given our critical environment with 24/7 on-call support, we deliberately prioritized minimizing risk, understanding that this would inherently mean a more measured pace for feature delivery to production. Branch by Abstraction, coupled with the rigorous quality verification techniques detailed later in this post, became our fundamental approach for ensuring this low-risk posture. This prioritization, however, naturally extended the overall timeline for the full migration, a conscious trade-off we embraced.

With Branch by Abstraction as our guiding principle, our first concrete application began with the ‘Product’ domain, aiming to create that initial abstraction layer.

Introducing the Abstraction Layer: ProductService

To bring structure to this chaos, our first crucial step was to introduce a unified access layer for “Product” data within Foo. This meant defining a new ProductService interface, which would become the sole conduit for Bar’s access to Product information. A key design decision was that this interface must not expose underlying Hibernate-proxied entities, but rather pure ProductDto objects.

We then implemented a FooProductServiceImpl for this interface. Crucially, this implementation still leveraged the existing Foo services, repositories, and DAOs for data access. However, by funneling all Bar’s interactions through the ProductService interface, we effectively decoupled Bar from Foo’s internal implementation details.

To handle the conversion from existing entities to the new DTOs, we integrated the MapStruct library into our codebase. This allowed us to gradually replace direct Product entity access in Bar with calls to the new ProductService interface, returning ProductDto objects. This initial refactoring was relatively straightforward and easy to split into smaller tasks, primarily because the ProductDto objects, at this stage, mirrored the data and fields of the original entities. However, we were able to simplify ProductDto significantly, because there were quite a few fields or methods that the Bar application didn’t need.

It’s important to note that, at this point, we deliberately didn’t over-optimize the ProductService interface’s structure or cohesion. It contained numerous methods with slightly differing parameters for retrieving Product data. The more complex task of rationalizing, removing duplicates, and condensing the interface into a leaner, more cohesive design was deferred to a later project phase.

Finally, to enforce this architectural boundary and prevent regressions, we introduced architecture tests using ArchUnit. These tests ensured that the Bar codebase could no longer directly reference or use the original Product entity, solidifying our new decoupling strategy.

Decoupling Product Data from the Database

Once the ProductService and ProductDto abstraction layers were established, our next major undertaking was to decouple the Bar application’s code from the shared database. At this stage, the ProductDto still contained its internal database identifier, and it often referenced other Foo domain objects (like IngredientDto) using their database identifiers as well. We recognized that relying on such internal database details was not only poor practice but would also be impossible once we transitioned to the new ProductAPI service.

Our solution involved systematically replacing these database identifiers with more stable, business-oriented identifiers. This transition was, once again, implemented gradually within the Bar codebase:

- First, the business identifier was introduced into the relevant DTO objects.

- Next, Bar’s code was updated to utilize this new business identifier.

- Finally, once a database identifier was no longer referenced anywhere in Bar’s code, it could be safely removed.

A second significant challenge was Bar’s direct database access, a consequence of the shared schema. Numerous queries within Bar involved JOINs directly to the PRODUCT table or its related tables. This, too, represented an anti-pattern and would be unsustainable after switching to the new ProductAPI service.

To address this, we systematically refactored Bar’s codebase to route all Product-related data access through the ProductService abstraction layer. The common pattern that emerged involved a Bar service layer first fetching its own Bar-specific domain objects via its repository layer. It would then determine what Product data was needed and subsequently fetch that information using the ProductService abstraction layer, effectively orchestrating data from both sources.

Gradual Switchover to the ProductAPI

With the Bar codebase now entirely decoupled from direct database queries for Product-related data, and our ProductDto and related DTOs cleaned of all internal database identifiers, we were finally ready to introduce a second implementation of the ProductService interface representing our new modern supplier.

This new implementation, aptly named ProductApiServiceImpl, was designed to fetch Product data from the external ProductAPI via its HTTP REST interface. Since the ProductAPI provided an OpenAPI description, we were able to leverage this to automatically generate a robust Java client. This generated client was then injected into ProductApiServiceImpl and further enhanced with Resilience4j features, including circuit breakers and retry functionality, to gracefully mitigate network transient errors and prevent API overload. As before, MapStruct played a vital role in seamlessly converting the data from the generated ProductAPI client classes into our established ProductDto objects.

At this juncture, we had two distinct implementations of the ProductService interface. The existing FooProductServiceImpl (using the old Foo internals) was designated as the default using Spring’s @Primary annotation. To manage the gradual transition, we began switching Bar’s services, one by one, to utilize the new ProductApiServiceImpl by selectively injecting it using Spring’s @Qualifier annotation. This allowed for fine-grained control over which parts of Bar began consuming data from the new API, enabling a safe and incremental cutover.

Quality Verification

When working with critical software that demands 24/7 on-call support, investing in rigorous quality verification is paramount. We were undertaking large-scale changes to the very core of the Bar application, and while most pull requests were of a manageable size, some were substantial. In total, this effort spanned over a hundred Jira issues. The pressing question was: how do we thoroughly verify quality to prevent those dreaded late-night calls to the on-call duty officer?

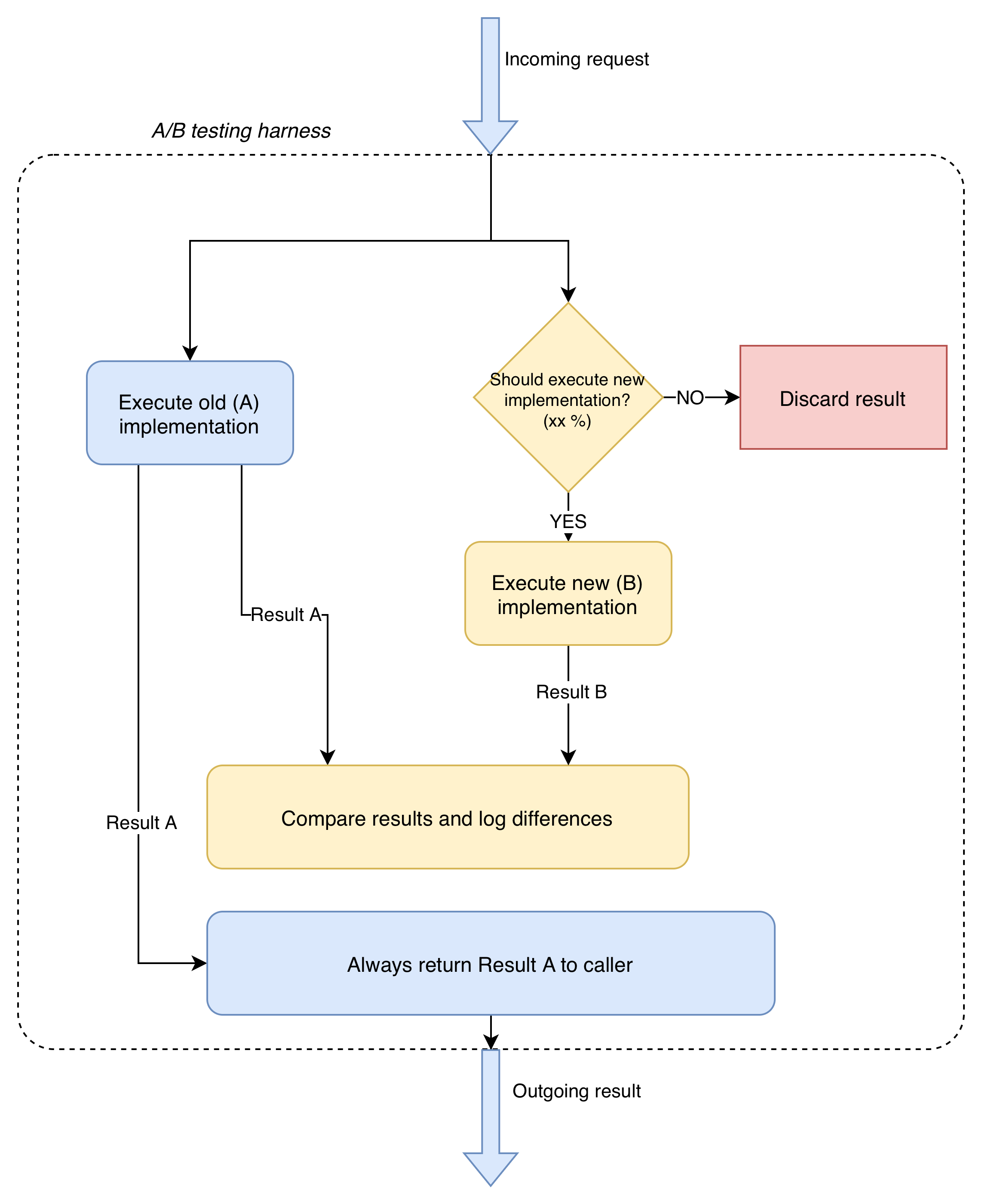

Our strategy, beyond maintaining good overall test coverage in new code, encompassed feature flags, A/B testing with result verification, and performance testing. We leveraged feature flags to dynamically switch between old and new implementations, for instance, during the migration from database identifiers to business-oriented ones. This mechanism provided a rapid rollback capability in production if any issues emerged, greatly reducing risk.

A/B testing with result verification proved to be another heavily utilized technique. For this, we relied on a custom implementation that was fortunately already available. Our team had previously developed this robust testing facility during an earlier migration from legacy Hibernate code. This A/B testing facility was designed to always return the result of the existing implementation, while simultaneously executing the new implementation and verifying its results against the old. We could precisely control the percentage of requests that executed the new implementation, mitigating potential high-load issues. The facility also supported custom verifiers, which proved essential since simple equality verification wasn’t always feasible. We conducted A/B testing in both our test environments and in production. Once we gained sufficient confidence that no discrepancies existed between the old and new implementation results, the A/B testing harness could be safely removed from the codebase.

For performance testing, we already utilized Locust to simulate the load of tens of client applications. While we didn’t specifically performance-test each new implementation in isolation, we rigorously checked for any regressions in overall performance test results between release candidates.

In addition to verifying functional correctness, our A/B testing facility also proved invaluable for performance analysis. By logging the execution times for both old and new implementation calls, we could meticulously inspect differences in performance. Given that the old implementation relied on direct database access while the new one fetched data over HTTP from an external service, inherent differences in access methods were expected. We observed a mixed bag: some data fetches were surprisingly faster with the ProductAPI implementation, particularly when the old SQL query was complex. However, others — especially for simple SQL queries fetching small datasets — were significantly slower through the ProductAPI. This disparity immediately highlighted the need for a caching solution to prevent Product data access from becoming a performance bottleneck. We began with a simple in-memory cache for each server instance, strategically caching frequently accessed Product instances. This foundational cache is designed for potential future migration to more robust solutions like Redis/Valkey, if needed. Furthermore, we identified opportunities for HTTP-level caching for larger datasets from the ProductAPI, and in some cases, we even refactored data access patterns to proactively gain performance benefits during the migration.

Where We Are Now

We’ve successfully introduced the ProductAPI-based implementation into production for a significant portion of Bar services. While a few issues were inevitably discovered only in production, our robust A/B testing facility proved invaluable. These issues were promptly identified via production logging and monitoring, and crucially, as the facility always returned results from the old implementation, there were no visible problems or service interruptions for our clients.

We acknowledge that a substantial migration effort still lies ahead to transition all remaining Bar services to the new implementation, but we are confident in achieving this goal soon. We anticipate that subsequent service migrations will be relatively more straightforward, benefiting from the lessons learned and issues resolved during the initial cutovers and A/B testing phases. For these later migrations, the need for extensive A/B testing might diminish, allowing for direct migration to the new implementation. This, of course, represents a critical trade-off between delivery speed and risk management, necessitating a careful, case-by-case evaluation.

Throughout this extensive process, celebrating small, yet significant, victories has been crucial for maintaining team morale and momentum. These milestones include:

- Ensuring the entire Bar codebase now exclusively utilizes the

ProductServiceabstraction layer. - Implementing architecture tests to prevent the reintroduction of the old

Productentity in the Bar application. - Eliminating all direct database queries within the Bar codebase that previously performed SQL JOINs to the

PRODUCTtable. - The first successful production migration of a Bar service to the

ProductAPI.

Key Takeaways and Lessons Learned

Our journey through this large-scale refactoring provided several invaluable lessons that are applicable to similar complex projects:

- Branch by Abstraction is Indispensable for Critical Systems: For high-traffic, continuously deployed applications, the incremental, low-risk nature of Branch by Abstraction is a powerful enabler for significant architectural changes without disruption.

- Enforcement through Architectural Tests is Key: Tools like ArchUnit are not just helpful; they are essential for preventing regressions and maintaining newly established architectural boundaries. Without them, the carefully built seams can easily fray.

- Proactive Resilience Pays Off: Integrating resilience patterns (like Resilience4j’s circuit breakers and retries) from the outset for new external API calls is non-negotiable. It protects the system from transient network issues and external service instability.

- Custom A/B Testing Facilities are Strategic Assets: For deep, internal refactoring where external tools might not suffice, investing in a custom, controlled A/B testing harness that can verify results in production while shielding end-users is incredibly powerful for de-risking deployments.

- Small Victories Fuel Long Journeys: Large, multi-month projects can be draining. Recognizing and celebrating intermediate achievements, even seemingly minor ones, keeps the team engaged, motivated, and focused on the long-term goal. It can be as simple as bubbles or cinnamon rolls in team retrospective.

- Continuous Evaluation of Trade-offs: Even with a clear strategy, the path evolves. Regularly reassessing the risk-vs-speed trade-off (e.g., for subsequent A/B testing) ensures agility and efficiency.

This refactoring has significantly modernized our architecture, improved our data access patterns, and laid a solid foundation for future development, all while maintaining the stability required by a critical 24/7 service.

Disclaimer: The content and ideas expressed in this blog post are entirely my own. However, Solita FunctionAI was utilized for grammar, spelling and stylistic review, and ChatGPT was used for visualizations.