Inspired by the recent Valio data breach, I started reflecting on my own security practices to see if there’s room for improvement.

My passwords are safely stored in a password manager, and two-factor authentication is enabled everywhere it’s supported, among other precautions. However, gaining access to browser cookies could bypass both password and two-factor authentication protections with ease.

Due to my work, I often have to install npm packages, and historically, some npm packages have contained malware (although not the libraries I use, at least as far as I know). These threats often focus on stealing data, including browser cookies—for example, in 2023, a specific version of the axios-proxy library contained a data-stealing malware called TurkoRAT.

So, the risk is far from nonexistent or imagined.

I recalled that, at least several years ago, Firefox profiles (including sessions) could be transferred to another machine simply by copying the profile folder, meaning there was no machine/user-specific encryption to make data theft more difficult.

I decided to check the current situation and investigate whether there’s a difference between browsers or operating systems in this regard.

I decided to examine the situation across three operating systems:

- Ubuntu 24.04 for the Linux world

- Windows 11 for Microsoft

- macOS Sequoia for Apple’s ecosystem.

I later had to adjust this plan for reasons explained further down in the text.

For browsers, I chose Firefox and Google Chrome for each operating system (since most browsers are built on these two engines).

I also included the default browsers, Microsoft Edge and Safari, just in case there are operating system-specific security mechanisms implemented in these browsers that Firefox or Chrome might not utilize for some reason.

Assessing cookie theft: methodology and targets

Test Phases:

- Can I read the cookies locally if I manage to run code locally?

- Can I read the cookies after copying the browser profile folder to another machine? (Technically, I don’t need the entire folder; a few files would suffice, but for simplicity, I copied the entire folder.)

Test Targets:

-

Logging in to Azure using a Microsoft account. This should closely resemble using an organizational AD account.

-

Logging in to GitHub using the service’s own login credentials. This should resemble using service-specific credentials.

To make the testing feasible within a reasonable time and effort, I decided to favor the operating system’s default installation methods and each browser’s default settings.

Reviewing the results

Let’s go over the results and try to understand what caused them. To improve readability, results are grouped by operating system below. The specific results are listed in the table below.

Phase 1 (local reading):

Success means that the cookies were successfully read locally using files found on disk and standard system APIs accessible to all applications (i.e., nothing was extracted from memory or by injecting into browser processes). Fail means that cookie access was unsuccessful.

| Browser | Linux | macOS | Windows |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chrome/Chromium | Success | Fail | Fail |

| Firefox | Success | Success | Success |

| Edge | - | - | Fail |

| Safari | - | Success | - |

Phase 2 (reading on another machine):

Success means that cookies were successfully read from files copied to another machine. Fail indicates that accessing the cookies from the copied data was not possible.

| Browser | Linux | macOS | Windows |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chrome/Chromium | Fail | Fail | Fail |

| Firefox | Success | Success | Success |

| Edge | - | - | Fail |

| Safari | - | Success | - |

Note: Using the copied browser data did not require the same operating system it was originally created on.

The choice of test services (Azure and GitHub) had no impact on the results—if cookie reading succeeded, it worked equally for both services, and the sessions were usable from another machine.

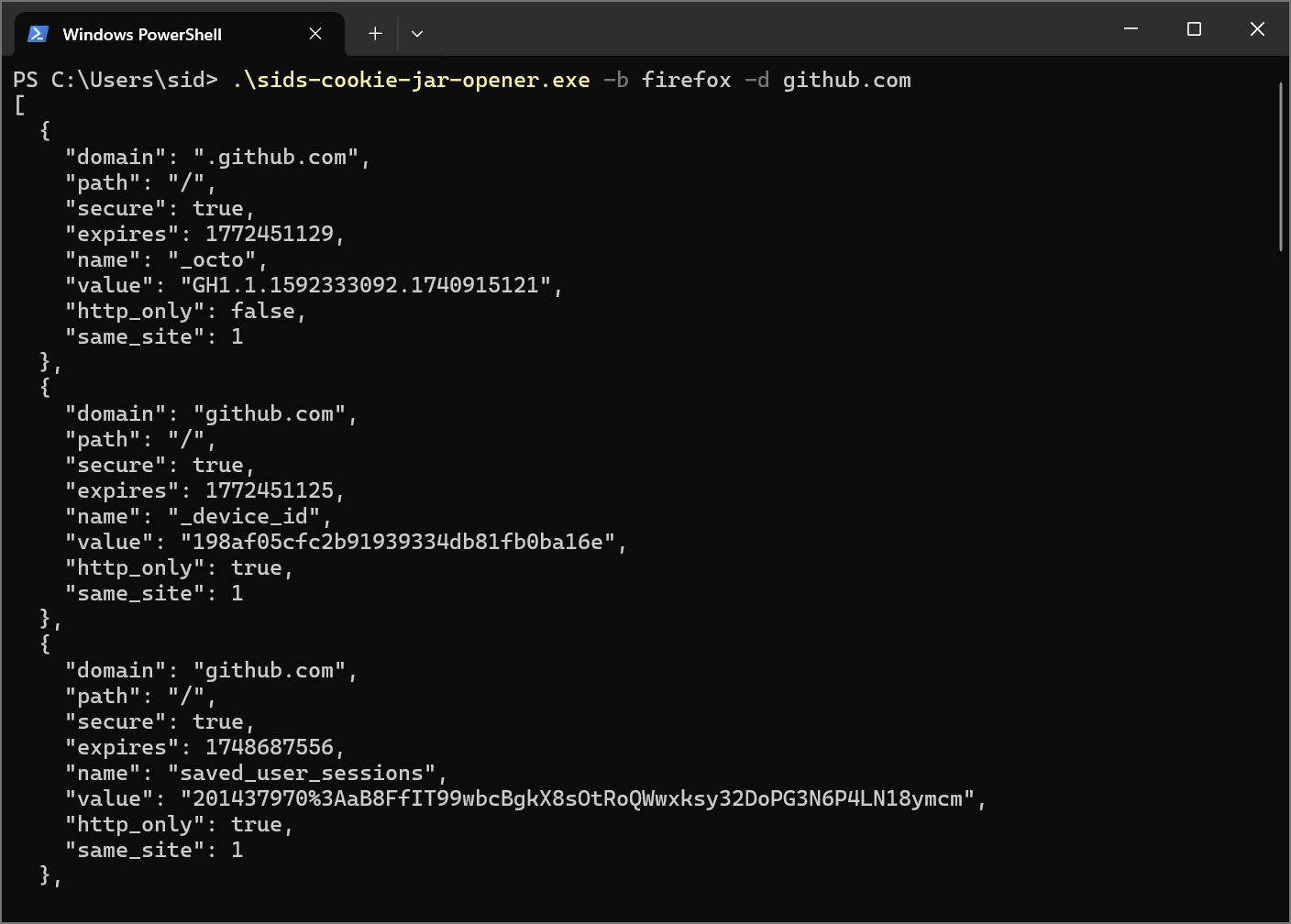

Reading Firefox cookies was successful on all operating systems without issues—both locally and on another machine where the necessary files had been copied. Firefox stores cookies in a plain-text SQLite database, so the outcome was quite expected.

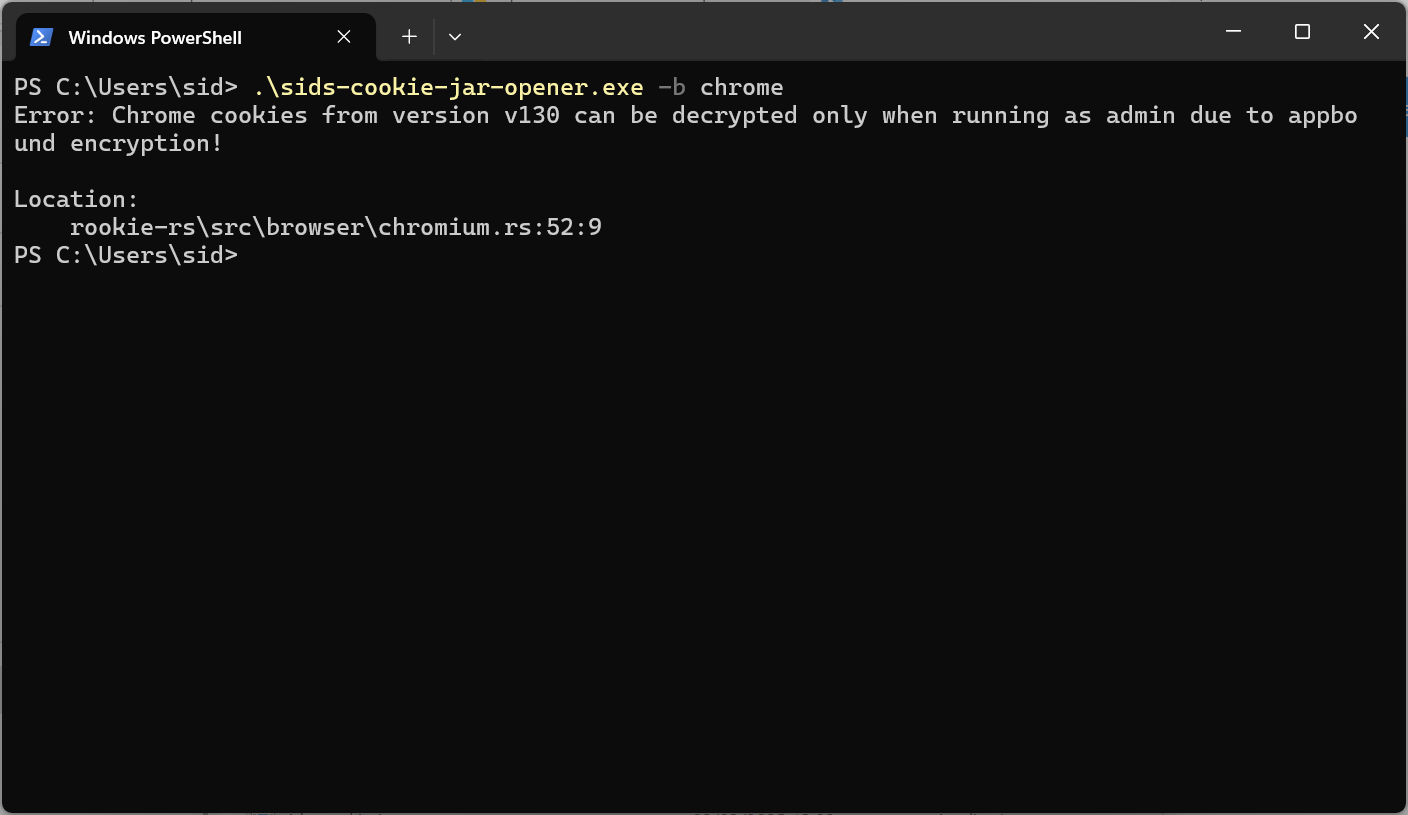

On Windows, reading cookies from both Chrome and Edge failed, as did with the copied files. Both browsers are Chromium-based, so a consistent result was anticipated. Chromium-based browsers on Windows store cookies in an SQLite database like Firefox, but unlike Firefox, they encrypt the cookies using the Data Protection API (DPAPI). This effectively ensures that only the respective browser, and not malware, can access the cookie encryption keys. More about this security mechanism can be found in a post on Google’s security blog.

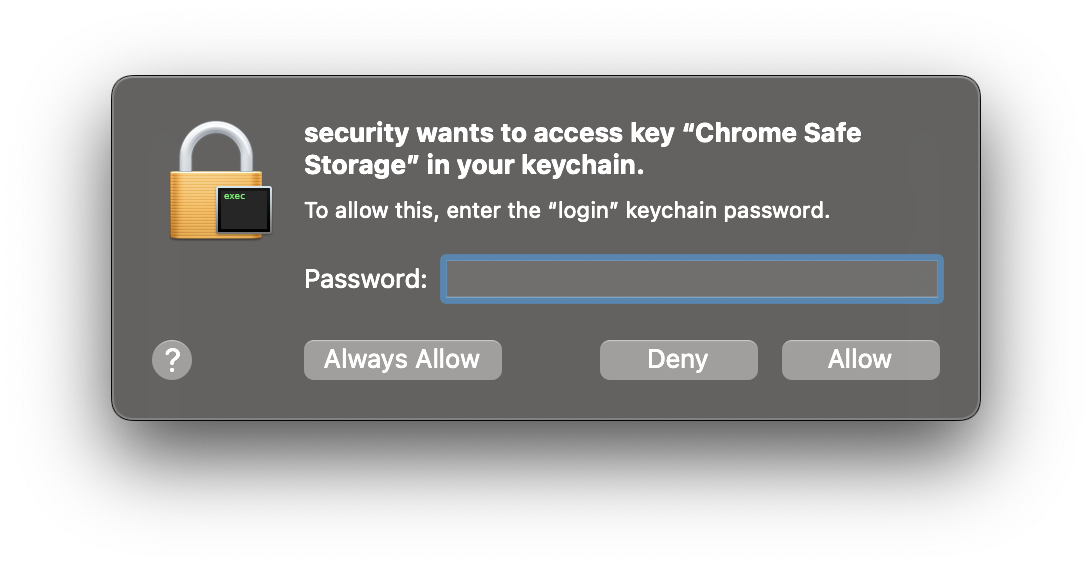

On macOS, reading Chrome cookies was interrupted by a prompt requesting Keychain permissions. Locally, when the required permissions were granted, reading the cookies worked without issues. On another machine, we would also need the encryption key stored in the Keychain.

Safari cookies could be read both locally and on another machine, but because the data was stored in Apple’s own binary format, finding the appropriate tool to read them was a bit more challenging. However, there is no separate encryption used—if you have the cookie file, you can read the contained data without needing keys from other sources.

A noteworthy point for macOS is the operating system’s compartmentalization of permissions. If the application responsible for copying the cookies doesn’t already have read permissions to the disk, reading will fail. In our hypothetical scenario, where cookie theft occurs via a compromised application library, we gave the application the necessary permission to simulate a scenario where the malicious library runs its functionality while being used as part of a locally run development environment.

On Ubuntu, reading Chromium cookies worked both locally and on another machine. This result differed most from my expectations.

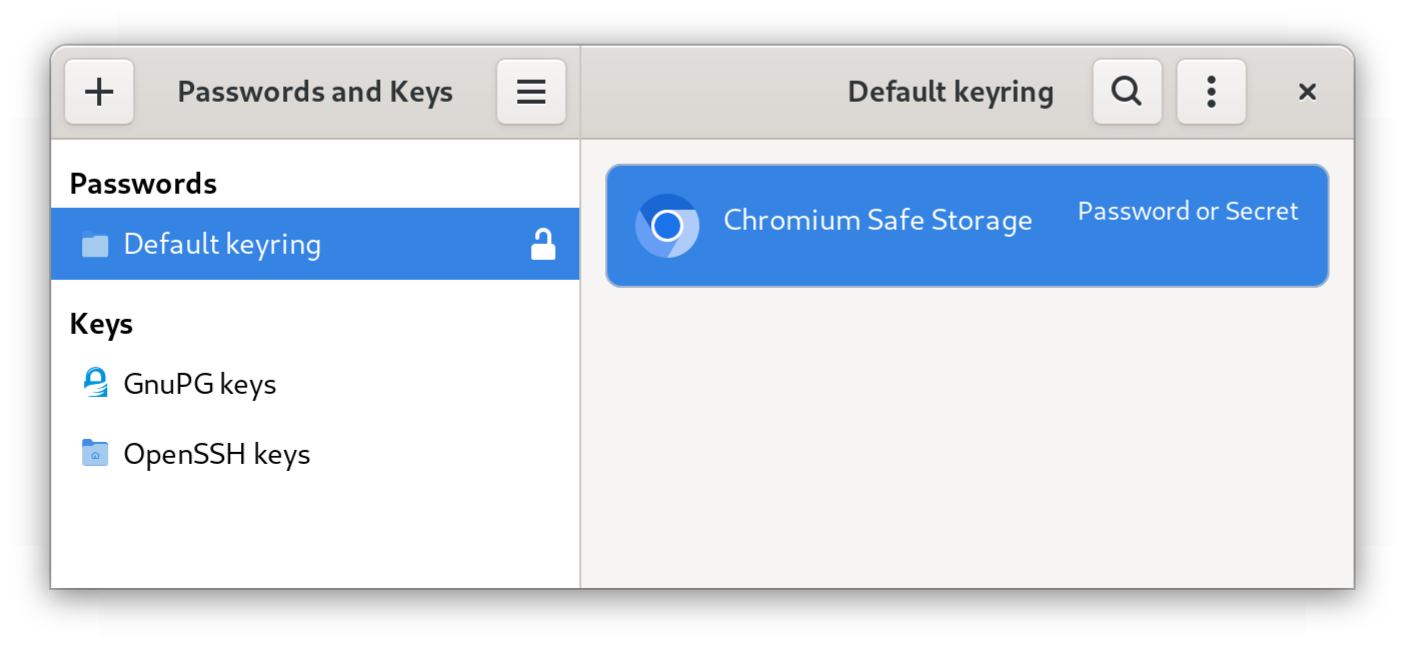

Initially, I assumed that Chromium would use the system’s wallet (such as gnome-keychain or kwallet), which would prevent cookie access without the appropriate key. However, the root cause turned out to be the use of a snap package. Snap packages are installed in their own sandbox with dependencies, meaning Chromium doesn’t have access to the wallet where the encryption key is stored unless the sandbox is specifically configured to allow it.

Since the test setup followed the recommended installation method and default settings, this hardening wasn’t applied. To verify this finding, I repeated the test on Fedora. There, reading cookies worked locally but not on another machine unless I also copied the encryption key from the Chromium Safe Storage in the wallet.

Conclusions

To summarize the findings briefly:

-

Firefox: Cookies are stored unencrypted and can be read directly if file access is gained.

-

Safari: Cookies are harder to access due to their format, but lack separate encryption.

-

Chromium-based browsers: Protection depends on the operating system and packaging method:

That said, I want to make it clear that I’m not advocating for any particular browser. Every user has different needs and criteria for choosing a browser. I just want to share my findings so you can make your own risk assessment and explore how you might improve your own situation—if you find it necessary after the assessment.

Firefox does not protect cookies in any way—if you gain access to the cookie file, you can read it without any extra effort or special tools.

Reading Safari cookies is a bit more work and requires tools designed for this purpose, but the protection relies solely on the fact that the user does not obtain the files.

Chromium-based browsers (Chrome, Chromium, Edge, etc.) offer a bit better protection. They use the operating system’s wallet solutions to store encryption keys, which increases the number of potential targets for theft. On Windows, the protection was straightforward—if I tried to read data with the wrong process, it was completely blocked. On macOS, it didn’t work either, but if the process was mistakenly granted Keychain access, there was nothing preventing the data from being read. On Linux, this entirely depends on the distribution and packaging method used. With snap packages and default settings, the wallet is not used at all. Even on Fedora, reading cookies worked locally without any additional permissions, so encryption mainly protected against file theft and access on another machine (or the need to steal the key as well). Both Linux and macOS wallets are also files on the filesystem, which could be stolen and transferred to another machine. Accessing them on another machine (or even locally if they haven’t been opened automatically during login) would require knowing the wallet’s password.

Firefox recently lost its distinguishing feature, in my view — the promise that they do not sell my data, which had previously set them apart from Chromium-based browsers.

For these reasons, I will likely stick to Chromium-based browsers in the future to make this attack vector at least somewhat more difficult than the available alternatives.

Note: All testing was performed using purpose-created user accounts that have since been deleted. As such, the cookies visible in the screenshots are no longer valid or usable at the time of publication ;)