Build systems: The bane of engineers’ existence.

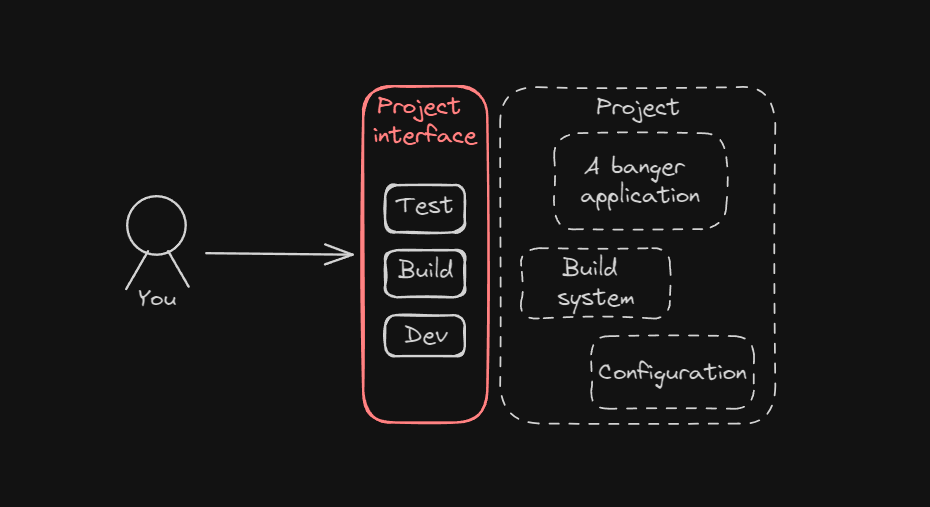

Most projects have a developer interface, be it a “start.sh”, a “make dev”

or even some incantations to copy-paste from the README. These interfaces tend to (d)evolve

into bespoke monstrosities that start to teeter on the line of “if it works, don’t touch it”.

These interfaces are also an important of the SDLC pipeline, as they remove discrepancies

between the developer workstations and CI, both using the same exact steps to reach a result.

You have probably seen a Bash script or a Makefile that looks like the content of some arcane scrolls and have no idea how it works, why it has to be like that, and why the heck does it not work on your machine.

The time comes to start a new project, or perhaps improve an old project, and you start googling for some options…

- “Just use a Makefile”

- “Have you tried a justfile?”

- “Taskfiles are awesome”

- “I tried Magefiles and am never going back”

- “Earthfiles are excellent”

…but you have no idea why you would pick one over another. Well, I tried them all out to see what works and what doesn’t. Follow along to see what might suit your use case the best. In this blog post we will replicate close to 1:1 copies of scripts and Makefiles used as a build system to see a side-by-side comparison. This means it will be a bit lengthy and contain a decent bit of code (about 2500 of the 5000 or so words), so strap in!

If you don’t care about the technical examples comparing each implementation, just skip to the end and check the comparison table to find the best choice for you.

Topics covered in this blog post

- The example application

- Setting the stage: A shell script

- I don’t want to have a degree in Bash (Makefiles)

- Just do it (justfiles)

- Makefile syntax is cumbersome, can’t I just write YAML? (Taskfiles)

- Total control (Magefiles)

- There’s always a price, but is it necessary to be paid? (Docker)

- The new kid on the block (Earthfiles)

- This is all cool and all, but what about CI?

- So what should I use?

- Source code used in this blog post

The example application

Our application is a simple HTTP server that serves templated HTML and a CSS file. For the sake of the example, it uses the Gin Web framework to have some dependency to pull in and it enforces a certain runtime file structure.

Application structure

$ tree ./app

./app

├── go.mod

├── go.sum

├── index.html

├── main.go

├── main_test.go

└── styles.css

Testing and building the application (on Linux and WSL)

One thing where Go shines in my opinion, is the easy-to-use toolchain.

We can easily run the following commands to run our tests:

cd app

go test ./... -v

As well as set some environment variables and then run a command to build it:

mkdir -p build

cd app

# Tell Go to build a x86_64 Linux binary without Cgo

export GOOS=linux

export GOARCH=amd64

export CGO_ENABLED=0

go build -o ../build/app main.go

The last thing we need is the assets the HTTP server is serving:

mkdir -p build

cp app/index.html app/styles.css build

Running the application

Now that we have an application package ready, we can start it up:

$ ./build/app

...

[GIN-debug] Listening and serving HTTP on :3000

Setting the stage: A shell script

So we have some environment variables, some specific arguments, and some file names to remember. The logical thing to do is to wrap it all in a script so we don’t have to remember these specifics during the day or when hopping between projects.

We could just copy-paste the commands above to a script and call it a day, that’s perfectly fine. But what if we set a fairly simple quality-of-life (QOL) limitation on ourselves; We want our script to run from anywhere and produce the same result, without affecting the existing workstation environment (such as other projects or the OS itself).

This way we can remove the need to remember what specific directory we have to be in to run the

scripts while also feeling safe that we don’t accidentally overwrite some existing files in our

filesystems. We could even alias the absolute paths of the scripts.

Test script: scripts/test.sh

This is what it will roughly look like with our “run anywhere” QOL in place (thank you Dave Dopson <3):

#!/usr/bin/env bash

# Fail fast

set -euo pipefail

# Ensure we are working in the correct directory (repo root)

SOURCE=${BASH_SOURCE[0]}

while [ -L "$SOURCE" ]; do # resolve $SOURCE until the file is no longer a symlink

SCRIPT_DIR=$( cd -P "$( dirname "$SOURCE" )" >/dev/null 2>&1 && pwd )

SOURCE=$(readlink "$SOURCE")

[[ $SOURCE != /* ]] && SOURCE=$SCRIPT_DIR/$SOURCE # if $SOURCE was a relative symlink, we need to resolve it relative to the path where the symlink file was located

done

SCRIPT_DIR=$( cd -P "$( dirname "$SOURCE" )" >/dev/null 2>&1 && pwd )

REPO_ROOT=$(realpath "$SCRIPT_DIR/..")

APP_DIR="$REPO_ROOT/app"

pushd "$APP_DIR" > /dev/null || exit 1

CWD=$(pwd)

# Build the binary

echo "Testing application $CWD"

go test ./... -v

popd > /dev/null || exit 1

That’s a whole lot of script just to run go test. Most of the script is just for that “simple”

piece of QOL in the first 15 or so lines.

What about building? Spoiler: It will be a lot of the same.

Build script: scripts/build.sh

This is what it will roughly look like with some extra developer experience echos in place:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

# Fail fast

set -euo pipefail

# Ensure we are working in the correct directory (repo root)

SOURCE=${BASH_SOURCE[0]}

while [ -L "$SOURCE" ]; do # resolve $SOURCE until the file is no longer a symlink

SCRIPT_DIR=$( cd -P "$( dirname "$SOURCE" )" >/dev/null 2>&1 && pwd )

SOURCE=$(readlink "$SOURCE")

[[ $SOURCE != /* ]] && SOURCE=$SCRIPT_DIR/$SOURCE # if $SOURCE was a relative symlink, we need to resolve it relative to the path where the symlink file was located

done

SCRIPT_DIR=$( cd -P "$( dirname "$SOURCE" )" >/dev/null 2>&1 && pwd )

REPO_ROOT=$(realpath "$SCRIPT_DIR/..")

# Make a destination directory

DEST_DIR="$REPO_ROOT/build"

echo "Ensuring $DEST_DIR exists"

mkdir -p "$REPO_ROOT/build"

# Set go build environment

export GOOS=linux

export GOARCH=amd64

export CGO_ENABLED=0

APP_DIR="$REPO_ROOT/app"

pushd "$APP_DIR" > /dev/null || exit 1

CWD=$(pwd)

# Build the binary

echo "Building application ($CWD/main.go) for: $GOOS/$GOARCH (Cgo: $CGO_ENABLED)"

go build -o "$DEST_DIR/app" "main.go"

# Copy assets

echo "Copying assets from $CWD to $DEST_DIR"

cp "index.html" "$DEST_DIR/index.html"

cp "styles.css" "$DEST_DIR/styles.css"

popd > /dev/null || exit 1

echo "Done. Build output:"

ls -laR "$DEST_DIR"

echo "******************************************************"

echo "Run in debug mode: $DEST_DIR/app"

echo "Run in production mode: GIN_MODE=release $DEST_DIR/app"

echo "******************************************************"

That’s a whole lot of script just to build our simple application. Imagine getting onboarded to a project that was full of scripts like the above.

Are there better alternatives? Something a bit more user and maintainer-friendly perhaps?

I don’t want to have a degree in Bash (Makefiles)

The next most common thing is probably GNU Make.

GNU Make is a tool which controls the generation of executables and other non-source files of a program from the program’s source files.

Make is primarily for building software incrementally with dependency tracking in place, but the

modern world also likes to use Make as a generic way to interface with a software project. That’s

also perfectly fine, but it requires some extra hacking, such as

.PHONY targets and

stringing together commands with && as every line is being run in a separate shell.

We can also mix and match with Make, making use of its dependency-tracking functionality while also giving simple commands for developers.

One big advantage of Make is that it is available on almost every Linux distribution you come

across, or in a core APT repository one apt install away.

One big disadvantage of Make is the amount of special syntax you just have to know. Ever debugged a

Makefile because you used spaces instead of tabs, = instead of :=, or quoted a string? I know I

have.

The Makefile

Let’s replicate the previous shell scripts into a Makefile but make use of some of the functionality

our new build system offers. Go already uses a build cache and has hasty build times but for the

sake of the example, let’s add in dependency tracking so we can skip the build if we did not change

any code. Let’s also suppress some of the commands (like echo) from the output, just printing

their own output.

SHELL:=/usr/bin/env bash

# The directory of this Makefile, regardless of current work directory

ROOT_DIR:=$(patsubst %/,%,$(dir $(realpath $(lastword $(MAKEFILE_LIST)))))

# Build paths

APP_DIR:=$(ROOT_DIR)/app

BUILD_DIR:=$(ROOT_DIR)/build

# Helpers

IN_APP_DIR:=cd $(APP_DIR) &&

# Go build environment settings

GOOS:=linux

GOARCH:=amd64

CGO_ENABLED:=0

all: test build

.PHONY:test

test:

@$(IN_APP_DIR) go test ./... -v

.PHONY:build

build: export GOOS:=$(GOOS)

build: export GOARCH:=$(GOARCH)

build: export CGO_ENABLED:=$(CGO_ENABLED)

build: $(BUILD_DIR)/app $(BUILD_DIR)/*.html $(BUILD_DIR)/*.css

@echo "Done. Build output:"

@ls -laR "$(BUILD_DIR)"

@echo "******************************************************"

@echo "Run in debug mode: $(BUILD_DIR)/app"

@echo "Run in production mode: GIN_MODE=release $(BUILD_DIR)/app"

@echo "******************************************************"

$(BUILD_DIR)/app: $(APP_DIR)/*.go

@echo "Ensuring $(BUILD_DIR) exists"

mkdir -p $(BUILD_DIR)

@echo "Building application ($(APP_DIR)/main.go) for: $(GOOS)/$(GOARCH) (Cgo: $(CGO_ENABLED))"

$(IN_APP_DIR) go build -o "$(BUILD_DIR)/app" main.go

$(BUILD_DIR)/*.html $(BUILD_DIR)/*.css &: $(APP_DIR)/*.html $(APP_DIR)/*.css

@echo "Ensuring $(BUILD_DIR) exists"

mkdir -p $(BUILD_DIR)

@echo "Copying assets from $(APP_DIR) to $(BUILD_DIR)"

$(IN_APP_DIR) cp "index.html" "$(BUILD_DIR)/index.html"

$(IN_APP_DIR) cp "styles.css" "$(BUILD_DIR)/styles.css"

.PHONY:clean

clean:

@echo "Deleting $(BUILD_DIR)"

@rm -r $(BUILD_DIR)

That’s already a lot more readable and maintainable but it is still quite noisy at first glance. That “run anywhere” QOL is now just a single line, but not that much easier to decipher than the 15 lines in the shell script.

This is probably quite close to the usual Makefile you would see used as a build system in the wild.

Now we can easily test and build our project with make or even build for Windows with

make build GOOS=windows. Pretty handy.

If you don’t care about dependency tracking (perhaps your build tool already does it for you, or is

fast enough, like go build), you can simplify the Makefile by concatenating the three

build-related recipes into one.

However, there are some more “modern” options available that are worth taking a look at, is there something even better? What if you just want to run commands, and don’t care about dependency tracking?

Just do it (justfiles)

![]()

Enter justfiles.

justis a handy way to save and run project-specific commands.

Justfiles are almost like Makefiles but more approachable, only exposing a few helpful functions and constants while adding some decorators. If you are familiar with Makefiles, justfiles should come pretty naturally to you. If you aren’t, the relevant documentation is all in a single README you can easily grok with the help of some CTRL+F.

Some disadvantages of justfiles include not having dependency tracking and the string interpolation outside of recipes being quite limited. You could of course build your own dependency tracking by saving checksums in a file and comparing them.

The justfile

Let’s replicate the Makefile as a justfile next. Pardon the syntax highlighting in the following sample, justfile is not exactly widely supported like the age-old Make.

# The directory of this justfile, regardless of current work directory

ROOT_DIR:=justfile_directory()

# Build paths

APP_DIR:=join(ROOT_DIR, "app")

BUILD_DIR:=join(ROOT_DIR, "build")

# Helpers

# No f-strings, yet: https://github.com/casey/just/issues/11#issuecomment-1546877905

IN_APP_DIR:=replace("cd {{APP_DIR}} &&", "{{APP_DIR}}", APP_DIR)

# Go build environment settings

GOOS:="linux"

GOARCH:="amd64"

CGO_ENABLED:="0"

default: test build

@test:

{{IN_APP_DIR}} go test ./... -v

@build $GOOS=GOOS $GOARCH=GOARCH $CGO_ENABLED=CGO_ENABLED:

echo "Ensuring {{BUILD_DIR}} exists"

@mkdir -p {{BUILD_DIR}}

echo "Building application ({{APP_DIR}}/main.go) for: {{GOOS}}/{{GOARCH}} (Cgo: {{CGO_ENABLED}})"

@{{IN_APP_DIR}} go build -o "{{BUILD_DIR}}/app" main.go

echo "Copying assets from {{APP_DIR}} to {{BUILD_DIR}}"

@{{IN_APP_DIR}} cp "index.html" "{{BUILD_DIR}}/index.html"

@{{IN_APP_DIR}} cp "styles.css" "{{BUILD_DIR}}/styles.css"

echo "Done. Build output:"

ls -laR "{{BUILD_DIR}}"

echo "******************************************************"

echo "Run in debug mode: {{BUILD_DIR}}/app"

echo "Run in production mode: GIN_MODE=release {{BUILD_DIR}}/app"

echo "******************************************************"

[confirm]

@clean:

echo "Deleting {{BUILD_DIR}}"

@rm -r {{BUILD_DIR}}

It’s almost 1:1 with a Makefile of the same degree. You can spot some goodies if you look closely:

justfile_directory(): Get the justfile directory, simple.@recipes: Invert@suppression and instead only print commands with@.[confirm]: Ask user y/n input before proceeding.

That’s a pretty neat build system if you ask me. No fuss, just do the thing I want to do, get on with the day, that’s all. I also like how strings are clearly strings, denoted by quotation.

Usage is the same as the Makefile, just replace make with just. If we don’t know the recipe,

we also get a simple helper:

$ just --list

Available recipes:

build $GOOS=GOOS $GOARCH=GOARCH $CGO_ENABLED=CGO_ENABLED

clean

default

test

What if we aren’t that used to Makefile syntax and want something we might be more familiar with?

Makefile syntax is cumbersome, can’t I just write YAML? (Taskfiles)

Why yes, of course, you can, we are living in the age of YAML. Your CI/CD is probably already in YAML, your microservices are probably already defined in YAML, majority of your other configuration is probably already in YAML.

Enter Taskfiles.

Task is a task runner / build tool that aims to be simpler and easier to use than, for example, GNU Make.

Taskfiles probably come pretty naturally to you if you have written some GitHub Actions or GitLab CI pipelines. Even if you haven’t, YAML is quite simple to read, write, and understand (until it isn’t).

Taskfiles support dependency tracking so you can skip unnecessary tasks and still get a simple build system. It’s not a workflow orchestration system though, so it lacks some features you might be used to from the pipeline YAMLs. For example, you cannot make clear and importable parametrized “template jobs” with expected inputs and outputs. You can hack around it with environment, though. Taskfiles can still be imported similarly as in other build systems so you can have one root Taskfile pulling in Taskfiles from other directories.

Taskfiles also use a built-in shell, removing that dependency.

The Taskfile

Next, let’s keep replicating the previous files into a Taskfile.

version: "3"

vars:

BUILD_DIR: "{{.TASKFILE_DIR}}/build"

APP_DIR: "{{.TASKFILE_DIR}}/app"

EXPOSED_AT: "3000"

tasks:

# What to run when calling 'task' without a target

default:

desc: "Test and build the application"

deps:

- test

- build

test:

desc: "Run unit tests"

# 'cd' before running cmds

dir: "{{.APP_DIR}}"

cmds:

- "go test . -v"

build:

desc: "Build the application binary and copy assets"

dir: "{{.APP_DIR}}"

# Suppress used commands from output (still prints command output)

silent: true

cmds:

- 'echo "Ensuring {{.BUILD_DIR}} exists"'

- 'mkdir -p {{.BUILD_DIR}}'

- 'echo "Building application ($PWD/main.go) for: $GOOS/$GOARCH (Cgo: $CGO_ENABLED)"'

- "go build -o {{.BUILD_DIR}}/app main.go"

- 'echo "Copying assets from ${{.APP_DIR}} to {{.BUILD_DIR}}"'

- "cp index.html {{.BUILD_DIR}}/index.html"

- "cp styles.css {{.BUILD_DIR}}/styles.css"

- 'ls -laR "{{.BUILD_DIR}}"'

- 'echo "******************************************************"'

- 'echo "Run in debug mode: {{.BUILD_DIR}}/app"'

- 'echo "Run in production mode: GIN_MODE=release {{.BUILD_DIR}}/app"'

- 'echo "******************************************************"'

# Variables this task takes (from user or other Taskfiles)

vars:

GOOS: '{{.GOOS | default "linux"}}'

GOARCH: '{{.GOARCH | default "amd64"}}'

CGO_ENABLED: '{{.CGO_ENABLED | default "0"}}'

# Environment variables to add to cmds. Here we pull the variables.

env:

GOOS: "{{.GOOS}}"

GOARCH: "{{.GOARCH}}"

CGO_ENABLED: "{{.CGO_ENABLED}}"

# Source files related to this task. Used for checksumming to skip unnecessary work.

# (See 'task build --status' before and after running 'task build')

sources:

- "{{.APP_DIR}}/*.go"

- "{{.APP_DIR}}/*.html"

- "{{.APP_DIR}}/*.css"

# Same as sources, but for what this task outputs.

generates:

- "{{.BUILD_DIR}}/app"

- "{{.BUILD_DIR}}/index.html"

- "{{.BUILD_DIR}}/styles.css"

clean:

desc: "Delete build artifacts"

cmds:

- "rm -r {{.BUILD_DIR}}"

# Which conditions must be met before running this task?

preconditions:

- sh: "test -d {{.BUILD_DIR}}"

msg: "Build directory does not exist. Nothing to delete."

Overall, that is quite clear. Each task tells what it depends on, what files it uses, what files it generates, and what commands it runs. Templating is simple in YAML unless you need a lot of conditionals (and you can probably use YAML anchors to keep it DRY). Taskfiles also come with the power of the Go templating language so you can make quite complex templates if required.

Now we can just task <some task> and be off to the races. If we don’t know what task we want to

run, we get a nice helper for free:

$ task --list

task: Available tasks for this project:

* build: Build the application binary and copy assets

* clean: Delete build artifacts

* default: Test and build the application

* test: Run unit tests

YAML is quite simple, but what if you need more control over the exact specifics, or want to bring in the full power of the operating system?

Total control (Magefiles)

![]()

Enter Magefiles.

Mage is a make/rake-like build tool using Go. You write plain-old go functions, and Mage automatically uses them as Makefile-like runnable targets.

Magefiles are Go programs, so they come with the full power of a programming language (as well as the full verbosity of one). You can compile the Magefile into a binary like any other Go program to remove any dependencies from the mix, but it’s simplest to use them in an environment that already has Go available. Otherwise, you will soon have a build system for your build system. :)

As per their nature, Magefiles also supports dependency-tracking, default targets, robust error handling, etc. You could even skip some CLIs completely and call functionality from their libraries directly with the help of some bindings. That’s pretty neat.

The Magefile

Replicating our previous examples in a magefile leads to such a long example that it has been cherry-picked to only the default target of testing and building, leaving some specifics out:

//go:build mage

// +build mage

package main

import (

/*...*/

"github.com/magefile/mage/mg"

"github.com/magefile/mage/sh"

"github.com/magefile/mage/target"

)

// Mage settings

var (

Default = TestAndBuild

)

const (

/*...*/

// Go build environment settings

GOOS = "linux"

GOARCH = "amd64"

CGO_ENABLED = "0"

)

// TestAndBuild runs the Test and Build targets

func TestAndBuild() error {

mg.Deps(Test, Build)

return nil

}

// Test runs unit tests

func Test() error {

return runInDir(appDir, "go", "test", "./...", "-v")

}

// Build builds the application binary and copies assets

func Build() error {

// Only build if necessary

changed, err := hasAppChanged()

if err != nil {

return err

}

if !changed {

fmt.Println("Build is up-to-date")

return nil

}

fmt.Printf("Ensuring %s exists\n", buildDir)

err = os.MkdirAll(buildDir, 0755)

if err != nil {

return err

}

goos, found := os.LookupEnv("GOOS")

if !found {

goos = GOOS

}

goarch, found := os.LookupEnv("GOARCH")

if !found {

goarch = GOARCH

}

cgo, found := os.LookupEnv("CGO_ENABLED")

if !found {

cgo = CGO_ENABLED

}

fmt.Printf("Building application (%s/main.go) for: %s/%s (Cgo: %s)\n", appDir, goos, goarch, cgo)

err = runInDir(appDir, "go", "build", "-o", fmt.Sprintf("%s/app", buildDir), "main.go")

if err != nil {

return err

}

fmt.Printf("Copying assets from %s to %s\n", appDir, buildDir)

err = runInDir(appDir, "cp", "index.html", fmt.Sprintf("%s/index.html", buildDir))

if err != nil {

return err

}

err = runInDir(appDir, "cp", "styles.css", fmt.Sprintf("%s/styles.css", buildDir))

if err != nil {

return err

}

fmt.Println("Done. Build output:")

out, err := sh.Output("ls", "-laR", buildDir)

if err != nil {

return err

}

if out != "" {

fmt.Println(out)

}

fmt.Println("******************************************************")

fmt.Printf("Run in debug mode: %s/app\n", buildDir)

fmt.Printf("Run in production mode: GIN_MODE=release %s/app\n", buildDir)

fmt.Println("******************************************************")

return nil

}

// runInDir runs a command in a directory, that always outputs, regardless of mage verbosity.

// Can be used for targets running in parallel and skip using the parallel-unsafe os.Chdir().

// Mage does not support concurrently running os.Chdir().

func runInDir(dir string, cmd string, args ...string) error {

command := exec.Command(cmd, args...)

command.Dir = dir

out, err := command.Output()

if err != nil {

return err

}

if len(out) != 0 {

fmt.Println(string(out))

}

return nil

}

type srcToArtifactMapping struct {

inputGlob string // What glob pattern produces output?

output string // What file or directory is the result?

}

// hasAppChanged returns true if any of the source files are newer than their corresponding

// build artifacts.

func hasAppChanged() (bool, error) {

var (

mappings = []srcToArtifactMapping{

{

inputGlob: fmt.Sprintf("%s/*.go", appDir),

output: fmt.Sprintf("%s/app", buildDir),

},

{

inputGlob: fmt.Sprintf("%s/index.html", appDir),

output: fmt.Sprintf("%s/index.html", buildDir),

},

{

inputGlob: fmt.Sprintf("%s/styles.css", appDir),

output: fmt.Sprintf("%s/styles.css", buildDir),

},

}

)

for _, m := range mappings {

changed, err := target.Glob(m.output, m.inputGlob)

if err != nil {

return false, err

}

if changed {

return true, nil

}

}

return false, nil

}

The magefile is using mg.Deps(...) to run the default targets concurrently, but here it already

hit a snag; Parallel targets cannot be used if the magefile contains unsafe usage, such as

os.Chdir(...) (so, cd), as those will affect the entire execution, not just one of the

concurrently executed targets it was called in. A custom implementation is needed.

It is also using target.Glob(...) as the dependency tracker. That syntax is a lot clearer than

the Makefile one in my opinion.

One could also add tests in the Magefile build system. For example, one could test if any configuration files it might generate has a certain configuration set, or if the directory structures are as expected. It can increase the quality of the end artifacts while also documenting the build process, creating a contract. It can also lead to better or more approachable maintenance of build systems when one does not have to fear if changing the pipeline code breaks something. Building robust validation is much easier with a proper programming language.

Mage also gives us a clear helper in case we forget what our targets do:

$ mage -l

Targets:

build builds the application binary and copies assets

clean deletes build artifacts

test runs unit tests

testAndBuild* runs the Test and Build targets

* default target

There’s always a price, but is it necessary to be paid? (Docker)

With all the options outlined above, there is some sort of bespoke dependency included in the setup.

- Shell scripts require a shell, usually the shell used is Bash.

- Makefiles require

make, which means a common Linux distribution or a Windows emulation like GnuWin. - Justfiles require the

justbinary. - Taskfiles require the

taskbinary. - Magefiles require the

magebinary and Go (or, a compilation step, and distribution of the built binary).

Nowadays we love containers as they encapsulate everything required to run something, whether it’s a backend application, a web app, or your development environment (see our recent blog post about Devcontainers).

Why wouldn’t we extend this to building our software and interfacing with our projects? No need to hassle with any extra dependencies, just have Docker and everything just worksTM. Most companies already have (or should have) their build environments dockerized for a healthy SDLC.

The Dockerfile

We want our workflow dockerized as well. The Dockerfile for the app would be something like the following:

FROM golang:1.22 as builder

ENV GOOS=linux

ENV GOARCH=amd64

ENV CGO_ENABLED=0

# Enable caching

RUN go env -w GOCACHE=/go-cache

RUN go env -w GOMODCACHE=/gomod-cache

# Setup workspace

WORKDIR /workspace

COPY ./Makefile /workspace

COPY ./app /workspace/app/

# Build with cache

RUN --mount=type=cache,target=/gomod-cache \

--mount=type=cache,target=/go-cache \

make

# Minimal distribution for low network costs and fast scaling

FROM scratch as app

USER nobody

# Setup Linux user (contains nobody:nogroup)

COPY ./passwd /etc/passwd

COPY ./group /etc/group

# Get build artifacts

COPY --from=builder /workspace/build/* /

# Run GIN in release mode by default

ENV GIN_MODE=release

EXPOSE 3000

ENTRYPOINT ["/app"]

Using the Go image to build our application, we can then package it in a minimal scratch container. Both the build and the application runs on any system with Docker installed and the final distribution size is around 15 megabytes.

Now we can extend our build tooling (e.g. Makefile) with something like the following:

docker: docker-build docker-run

docker-build:

docker build --tag example-app .

docker-run:

docker run -p 3000:3000 example-app

Now just make docker and we are ready to go! In reality, it tends to get slightly more

complicated with watchers for live updates where you would have to mount volumes in, but that’s

outside of the scope of this blog post.

What if we didn’t manage a pile of Dockerfiles and had a single file to rule them all?

The new kid on the block (Earthfiles)

Here comes Earthly, shaking the world up with Earthfiles.

Fast, consistent builds with an instantly familiar syntax – like Dockerfile and Makefile had a baby.

Everything now runs in a container. There are no other dependencies than Docker (and optionally,

the earthly CLI) to take care of. Just boot up the buildkit as a container and everything just

works. That’s a love song for the DevOps engineer’s ears. No more slicing and dicing up JDKs in

rotting Jenkins hosts.

It’s worth noting that Earthly collects anonymized analytics data, which you might want to opt-out of.

The Earthfile

The earthly CLI offers a Dockerfile-to-Earthfile conversion command earthly docker2earthly, but

it did not produce a valid Earthfile. Even though the syntax is quite close to Docker, some

implementation differences exist. In this case, the problem was the USER statement in the

original Dockerfile being before the COPY ... /etc/... statements, failing in a fairly cryptic

error. The conversion also produced an Earthfile of an older version, so in the end, it had to be

manually written.

Here is what an Earthfile that replicates our previous examples would look like:

VERSION 0.8

FROM golang:1.22

ARG --global ROOT_DIR="/workspace"

ARG --global APP_DIR="app"

ARG --global BUILD_DIR="build"

WORKDIR $ROOT_DIR

RUN go env -w GOCACHE=/go-cache

RUN go env -w GOMODCACHE=/gomod-cache

all:

BUILD +test

BUILD +build

BUILD +assets

deps:

COPY ./$APP_DIR/go.mod ./$APP_DIR/go.mod $ROOT_DIR/$APP_DIR

WORKDIR $ROOT_DIR/$APP_DIR

RUN --mount=type=cache,target=/go-cache --mount=type=cache,target=/go-modcache go mod download -x

test:

FROM +deps

COPY ./$APP_DIR $ROOT_DIR/$APP_DIR

WORKDIR $ROOT_DIR/$APP_DIR

RUN go test . -v

build:

FROM +deps

WORKDIR $ROOT_DIR

RUN mkdir -p $ROOT_DIR/$BUILD_DIR

COPY ./$APP_DIR $ROOT_DIR/$APP_DIR

ENV GOOS="linux"

ENV GOARCH="amd64"

ENV CGO_ENABLED="0"

RUN cd $ROOT_DIR/$APP_DIR && \

go build -o "$ROOT_DIR/$BUILD_DIR/app" main.go

SAVE ARTIFACT --keep-ts $ROOT_DIR/$BUILD_DIR/* $ROOT_DIR/$BUILD_DIR/* AS LOCAL ./$BUILD_DIR/

assets:

WORKDIR $ROOT_DIR

RUN mkdir -p $ROOT_DIR/$BUILD_DIR

COPY ./$APP_DIR/styles.css $ROOT_DIR/$BUILD_DIR

COPY ./$APP_DIR/index.html $ROOT_DIR/$BUILD_DIR

SAVE ARTIFACT --keep-ts $ROOT_DIR/$BUILD_DIR/* $ROOT_DIR/$BUILD_DIR/* AS LOCAL ./$BUILD_DIR/

clean:

LOCALLY

RUN rm -r ./$BUILD_DIR

docker-build:

FROM scratch

ARG TAG="latest"

COPY ./passwd /etc/passwd

COPY ./group /etc/group

USER nobody:nogroup

COPY +build$ROOT_DIR/$BUILD_DIR/* /

COPY +assets$ROOT_DIR/$BUILD_DIR/* /

ENV GIN_MODE=release

EXPOSE 3000

ENTRYPOINT ["/app"]

SAVE IMAGE example-app:$TAG

docker-run:

LOCALLY

ARG TAG="latest"

ARG EXPOSED_AT="3000"

ARG GIN_MODE=""

IF test "$GIN_MODE" = ""

WITH DOCKER --load=+docker-build

RUN docker run -p $EXPOSED_AT:3000 example-app:$TAG

END

ELSE

WITH DOCKER --load=+docker-build

RUN docker run -p $EXPOSED_AT:3000 -e GIN_MODE=$GIN_MODE example-app:$TAG

END

END

dockerfile:

ARG TAG="latest"

FROM DOCKERFILE .

SAVE IMAGE example-app:$TAG

docker:

BUILD +docker-build

BUILD +docker-run

docker-dev:

BUILD +docker-build

BUILD +docker-run --GIN_MODE="debug"

It truly is “like Dockerfile and Makefile had a baby”; We have a defined set of targets, running Dockerfile-like recipes. If you are familiar with Makefiles and Dockerfiles, it is probably quite understandable already, but let’s go through some of the more earthly bits, starting from the top:

- First, a default base environment is defined for every target (a Go container). Some global variables are also defined.

- We have a default target (

all:) that uses the special instructionBUILD, to run the specific+targets (concurrently). - In the

testandbuildtargets, a dependency on thedepstarget exists, so a valid result from that target must exist to proceed. If it does not, it gets run first. - In the

buildandassetstargets an artifact is saved locally to the same build directory as in previous examples. It is given in the format “what, identified by, where”. - In the

cleantarget, the execution hops out of the containerized context, and runs somethingLOCALLY, on the host. - In the

docker-buildtarget, the previous targets are again leveraged as dependencies in theCOPYinstruction. The targets stay fairly lean and work both on the host and in the container. That’s neat. Note that it does not fetch specific files, but the entire saved artifact. The format is “+target/identified by”. - In the same target, instead of having a

docker build --tag ..., usingSAVE IMAGEaccomplishes the same thing. - In the

docker-runtarget, we hop from a local context back into a Docker context, loading the previousdocker-buildresult as the image to use. - If one doesn’t want to go full on Earthfile just yet,

FROM DOCKERFILEis also an option!

If you want to embrace Docker with open arms, Earthfiles seems like a great candidate when choosing the next project setup. This is especially useful in making workflows between the developer workstations and the CI runners seamless.

This is all cool and all, but what about CI?

Each of the examples laid out above comes with some sort of dependency. Most dependencies can be handled in Docker but using one of these build systems would require you to update your standard build environment in your organization with the new and shiny build tools in place, be it a VM image, a Docker container, or installing the tools directly on the CI runner.

If you dockerize your builds, that point becomes moot and you can run everything in containers with no extra dependencies other than Docker which most CI systems already have.

To show what building each of these projects looks like with the full setup, check the example

Github Actions jobs below. Note that I’ve previously omitted the Docker jobs from the example code

samples to keep the length a bit shorter, but all of the files are at parity with an equivalent

... docker-build used in the following example.

jobs:

# This job requires Go on the host for the 'go' commands like build and test.

# Runs default target of each build system

build-on-host:

name: "Build application locally"

strategy:

matrix:

include:

- entrypoint: "make"

image: "golang:1.22"

- entrypoint: "~/bin/just"

image: "golang:1.22"

setup: |

mkdir -p ~/bin

curl --proto '=https' --tlsv1.2 -sSf https://just.systems/install.sh | bash -s -- --to ~/bin

- entrypoint: "~/bin/task"

image: "golang:1.22"

setup: |

mkdir -p ~/bin

sh -c "$(curl --location https://taskfile.dev/install.sh)" -- -d -b ~/bin

- entrypoint: "mage"

image: "golang:1.22"

setup: |

git clone https://github.com/magefile/mage

cd mage

go run bootstrap.go

# We could install and bootstrap the CLI. ...or we could just use the container!:

- entrypoint: "earthly +all"

image: "earthly/earthly"

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

container: "${{matrix.image}}"

steps:

- name: Check out repository code

uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: "Setup build environment for ${{matrix.entrypoint}}"

if: "${{matrix.setup}}"

run: "${{matrix.setup}}"

- name: "Run ${{matrix.entrypoint}}"

run: "${{matrix.entrypoint}}"

- name: Print result

run: "ls -la build"

# This job only requires Docker.

# Runs the Docker build target of each build system.

build-docker:

name: "Build application in Docker"

strategy:

matrix:

include:

- entrypoint: "make docker-build"

- entrypoint: "~/bin/just docker-build"

setup: |

mkdir -p ~/bin

curl --proto '=https' --tlsv1.2 -sSf https://just.systems/install.sh | bash -s -- --to ~/bin

- entrypoint: "~/bin/task docker-build"

setup: |

mkdir -p ~/bin

sh -c "$(curl --location https://taskfile.dev/install.sh)" -- -d -b ~/bin

- entrypoint: "~/bin/mage dockerBuild"

setup: |

mkdir -p ~/bin

wget https://github.com/magefile/mage/releases/download/v1.15.0/mage_1.15.0_Linux-64bit.tar.gz

tar xvf mage_1.15.0_Linux-64bit.tar.gz mage

mv mage ~/bin

- entrypoint: "earthly +docker-build"

image: "earthly/earthly"

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

container: "${{matrix.image}}"

steps:

- name: Check out repository code

uses: actions/checkout@v4

- name: "Setup build environment for ${{matrix.entrypoint}}"

if: "${{matrix.setup}}"

run: "${{matrix.setup}}"

- name: "Run ${{matrix.entrypoint}}"

run: "${{matrix.entrypoint}}"

- name: Print result

run: "docker images | grep example-app"

Each of the options comes with some setup involved, apart from Earthfiles. The recommended installation methods of each build system also recommend piping curl output to your shell which I’m not personally a fan of.

So what should I use?

The answer is the most ubiquitous one in the history of software engineering: It depends and each comes with its own tradeoffs. Simplicity? Ergonomics? Multi-platform? Dependencies? All in all, each of the systems gives a nearly identical interface for the user but just comes with different implementations under the hood.

Maybe the following comparison between each option might help you to make a decision where

- Ergonomics: Developer and integration experience

- Simplicity: Maintainability, readability, and quirkiness

- Velocity: The time it takes to get started

| Choice | Dependencies | Language | Multi-platform | Ergonomics | Simplicity | Velocity | Analytics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shell scripts | The chosen shell | Shell | Not really | 2/5 | 2/5 | 5/5 | No |

| GNU Make | Make and the chosen shell | Makefile | Not really | 3/5 | 3/5 | 3/5 | No |

| Just | Just and the chosen shell | Makefile-like | Not really | 4/5 | 4/5 | 3/5 | No |

| Task | Task only | YAML | Yes | 4/5 | 5/5 | 4/5 | No |

| Mage | Mage and Go (but can be compiled) | Go | Yes (but not for free) | 4/5 | 3/5 | 2/5 | No |

| Earthly | Docker only | Dockerfile-like | Yes | 5/5 | 4/5 | 3/5 | Opt-out |

If you care about the author’s personal choice, I will keep using what the organization I’m working with is using already, but give Earthfiles and justfiles a fair chance in my personal projects. I might give Mage a go if I’m building something with Go (pun not intended, heh).

Source code used in this blog post

You can find all the code in GitHub.

Happy hacking fellow developers! :) <3