Disclaimer

This post presumes, you’ve got preliminary knowledge of Clojure as a language, and it’s basic tools, such as the REPL.

A lot of the things I’ll go over are a result of a cooperation with my colleague Tuomas Rinne. He’s had a profound impact on the way I work with the aforementioned tools. He’s been the one to introduce me to a lot of the stuff here, so it might as well be him writing this post too. Just to give credit where credit is due.

Introduction

For the past 6 years or so the bulk of my front end development has been done using ClojureScript and Re-Frame. Before that, I spent a few years working on a project that used “bare bones” Reagent. Before that it was mostly JQuery, Knockout, etc. and some other stuff that I’m not particularly proud of.

In the early days, I’ve had 3 major gripes working with the front end that could be summed up to:

- Complex frameworks, with tons of new concepts, bizarre workflows etc.

- Poor workflows during development

- Poor testability

And to be totally honest, there’s always the tooling and the whole mess with NPM and the like. Unfortunately there’s no relief for that here.

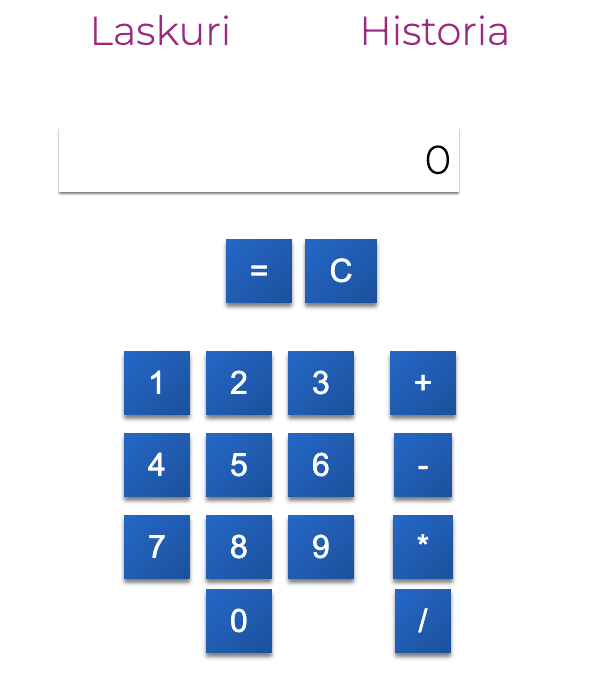

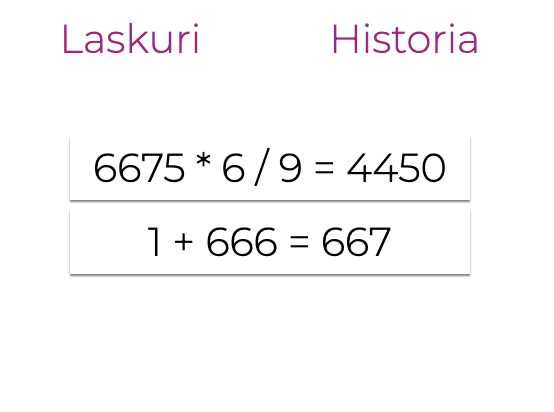

Example project

I’ve made a small example project to elaborate some of these concepts that I’ll use as a reference. You can find it here. It’s a calculator. Which holds a record of the previous calculations…woo.

These are main tools that I’ve used and their purpose in a nutshell.

ClojureScript

ClojureScript is basically a compiler for compiling Clojure into JavaScript. Uses Google Closure for optimization.

Leiningen

Tool for Clojure project management. In this case used only for creating the project using a template Re-Frame -template project. A rather nifty way to get a working project template straight out of the box.

Clojure-CLI (deps.edn)

ClojureScript libraries and dependencies are handled using deps.edn in this project.

Shadow-CLJS

ClojureScript build tool used in this project. Handles integration with NPM, live reload, REPL etc.

Reagent

Simple interface for ClojureScript to React. Enables writing React-components using ClojureScript functions. Instead of the React’s “not quite HTML” uses Hiccup, which represents HTML via Clojure basic datastructures (maps and vectors).

Re-Frame

ClojureScript frontend framework. “Last in the chain”, meaning it builds on Reagent and enables building React components. Alters the React basic paradigm a bit. Basically Re-Frame events are the only means for mutating the appstate and views react to them via subscriptions.

One of the main selling points of Re-Frame is its data-oriented design. This design choice is key for making the application using the Re-Frame framework more testable by steering implementation towards more pure functions and keeping side effects at a minimum and isolated in specific places to make the application more testable.

Stylefy

CLJS-library made by our very own Jari Hanhela, which enables writing CSS styles as Clojure data and attaching them to Reagent components.

Velho DS

Reagent component library developed by the Velho alliance.

Basic concepts

Or maybe I should refer this chapters as scarcity of them. This is one of the main selling points of this setup for me. Basically the only things you need to know are the following:

1. Appstate

Also known as “db” with Re-Frame. Re-Frame takes all the appstate and stores it in a so-called big atom. The main issue I had working with just Reagent was that it doesn’t take long for the application state to blow up all over the place, making development and testing a real pain. With re-frame, you have it neatly stored in a single place.

2. Subscriptions

To put it short, subscriptions simply are a way to get the state out to your views. They provide the portion of the appstate that a single component or view is interested in a format that suits its needs.

Subscriptions react to changes in the appstate. Subscriptions can be composed number of other subscriptions or calculated on the fly. They limit the data that is visible for the UI component and thus affects on re-rendering components only when needed.

3. Events

Whereas subscriptions are a way of getting the state out, events are a way of getting user input from the UI and mutating the appstate (db) in event handlers. For side effects (handling local storage, HTTP request etc.) there is a concept of effects in Re-Frame but that is out of scope of this post.

4. Views

Basically React-components written using Hiccup. These components react changes in the appstate via subscriptions by re-rendering themselves and cause affect changes the state via events.

And that’s basically it. Obviously you need to have something to work with e.g. routing, styling etc. but these four concepts will get you surprisingly far.

Olive Hine has a good blog post that touches on at least some of the topics here.

How I personally like to arrange an app

After a very long time of pondering with a number of different colleagues, I really find the following structure neat and somewhat easy to maintain and expand over:

Routes

I’ve used Metosin’s Reitit in my example project, that tie up a view to a URL quite nicely. Nothing fancy here. It’s merely where most things kick off.

(ns tuhoaja666.routes

(:require [tuhoaja666.calculator.view :as calculator-view]

[tuhoaja666.history.view :as history-view]))

(def routes

[["/"

{:name ::calculator

:view calculator-view/calculator}]

["/history"

{:name ::history

:view history-view/history-page}]])

MVCish structure

The rest of the structure follows somewhat in the vein of a traditional MVC model forced in to this world with light hammering.

The view

The views that the routes tie into are functions that return hiccup, that then on renders into react components. In their simplest form, they can look something like this:

(ns tuhoaja666.calculator.view

(:require [re-frame.core :as re-frame]

[stylefy.core :as stylefy]

[tuhoaja666.calculator.controller]

[tuhoaja666.calculator.model :as model]

[tuhoaja666.calculator.styles :as styles]

[velho-ds.atoms.area :as areas]

[velho-ds.atoms.button :as button]))

(defn number-button

([number]

(number-button false number))

([wide? number]

[:div (stylefy/use-style (if wide?

styles/wide-button

styles/button))

[button/primary-small {:content (str number)

:on-click-fn #(re-frame/dispatch [model/append-value number])}]]))

(defn function-button [name function-fn]

[:div (stylefy/use-style styles/button)

[button/primary-small {:content name

:on-click-fn function-fn}]])

(defn current-value []

(let [current-value (re-frame/subscribe [model/current-value])]

[:div (stylefy/use-style styles/output-grid)

[areas/shadow-area {:styles styles/output-field}

[:span @current-value]]]))

(defn calculator []

[:div (stylefy/use-style styles/main-container)

(current-value)

[:p]

[:div (stylefy/use-style styles/function-grid)

[function-button "=" #(re-frame/dispatch [model/evaluate])]

[function-button "C" #(re-frame/dispatch [model/reset])]]

[:p]

[:div (stylefy/use-style styles/numpad-grid)

[number-button 1]

[number-button 2]

[number-button 3]

[function-button "+" #(re-frame/dispatch [model/add])]

[number-button 4]

[number-button 5]

[number-button 6]

[function-button "-" #(re-frame/dispatch [model/substract])]

[number-button 7]

[number-button 8]

[number-button 9]

[function-button "*" #(re-frame/dispatch [model/times])]

[number-button true 0]

[function-button "/" #(re-frame/dispatch [model/division])]]])

As said before, they merely define HTML tags, get their data via subscriptions and interact with the state via events. What could be improved in the above example would be to completely take out the Re-Frame specific stuff from the components themselves up until to a point where they are just pure functions.

I’ve also liked to move all style specific code into a separate file just to keep things as tidy as possible. As mentioned earlier, I’ve used Stylefy in this project. It mainly just creates inline CSS. So the styles for the previous view look like the following:

(ns tuhoaja666.calculator.styles

(:require [velho-ds.tokens.font :as font]

[velho-ds.tokens.font-size :as font-size]))

(def main-container

{:padding-top "2rem" })

(def button

{:display "grid"})

(def wide-button

(merge button {:grid-column "1 / 4"}))

(def output-grid

{:display "inline-grid" ;

:grid-template-rows "40px"

:grid-template-columns "100px 40px"

:grid-gap "1px"

:justify-items "center"

:align-items "center"})

(def output-field

{:font-family font/font-family-heading

:font-size font-size/font-size-x-large

:width "12rem"

:text-align "right"})

(def function-grid

{:display "inline-grid" ;

:grid-template-rows "40px"

:grid-template-columns "40px 40px"

:grid-gap "1px"

:justify-items "center"

:align-items "center"})

(def numpad-grid

{:display "inline-grid"

:grid-template-rows "40px 40px 40px"

:grid-template-columns "40px 40px 40px 60px"

:grid-gap "1px"

:justify-items "center"

:align-items "center"})

In case you haven’t already picked up on it, what’s being used here are just maps and vectors to define the components. Clojure’s very basic datastructures. As the age-old mantra goes: it’s just data, baby. And I really like it.

The model

The model resembles a C header file. Basically “introducing a single view”. Usually what finds it’s way here is paths within the db, subscriptions, events and specs. So all the stuff that you need to refer to when working with a single view.

(ns tuhoaja666.calculator.model

(:require [cljs.spec.alpha :as s]))

;; Paths

(def base-path [:calculator])

(def current-value-path (conj base-path :current-value))

(def clause-path (conj base-path :clause))

;; Subscriptions

(def current-value :calculator/current-value)

;; Events

(def append-value :calculator/append-value)

(def reset :calculator/reset)

(def add :calculator/add)

(def substract :calculator/substract)

(def times :calculator/times)

(def division :calculator/division)

(def evaluate :calculator/evaluate)

;; Specs

(s/def ::literal (s/or

:n number?

:f #{+ - / *}))

(s/def ::clause (s/coll-of ::literal))

This is pretty handy, when you have global var which usage can be easily traced. In addition to help keep your appstate in order, it’s quite convenient to just build your path as a vector and just conjoin stuff to it. This structure goes nicely hand in hand when using the Re-Frame 10x debugging tools.

Also schemas, in this case Clojure specs, are stored here. They are used to define the datastructures used by this view and this part of the neighbourhood in the appstate.

The controller

This is where the actual calculation happens. The controller defines the implementation of the subscriptions and events introduced in the model file.

(defn current-value [db]

(get-in db calculator-model/current-value-path))

(re-frame/reg-sub calculator-model/current-value current-value)

(defn evaluate [{:keys [db]} _]

(let [clause (conj (vec (get-in db calculator-model/clause-path))

(get-in db calculator-model/current-value-path))

result (evaluate-clause clause)]

{:db (-> db

(assoc-in calculator-model/current-value-path result)

(assoc-in calculator-model/clause-path []))

:dispatch [history-model/add-clause {:clause clause :result result}]}))

(re-frame/reg-event-fx calculator-model/evaluate evaluate)

For testing purposes and for keeping up with general hygiene, it’s a good practice to deliberately separate your event and subscription definitions from the actual functions that they implement. I’ll get back to it later on.

The REPL and debugging

Having a full-fledged REPL when working on front end for me has been just simply put wonderful. ShadowCLJS provides this out of the box. Being able to tap in to a long workflow e.g. with context capture has made debugging some hairy cases so much more nicer.

E.g. If we were to have a problem with our example when evaluating a clause, we could just easily take function that implements the events functionality and def it’s params to a global var like so:

(defn evaluate-clause [clause]

(assert (s/valid? ::calculator-model/clause clause)

(str "Invalid clause. Will not evaluate: " (s/explain-str ::calculator-model/clause clause)))

(def clause clause) ;; <----

(:previous-value

(reduce

(fn [{:keys [previous-value operator] :as acc} current]

(if (fn? current)

(assoc acc :operator current)

{:previous-value (operator previous-value current)}))

{:previous-value (first clause)}

(rest clause))))

So now we could just start debugging away merrily the body of that function. This means in addition just viewing the last params of the function, you can simply run the body of the function with the last parameters it was called with over and over again and see how it works. This might not seem much, but with long and complex workflows, this has kept me sane in a number of case. Yes I know, there’s the browser console, but it’s just not the same.

What’s great about this approach is that it provides inputs and outputs for unit tests right to your doorstep. Just add assertions.

Testing

Related to the previous chapter, what’s great is that the same REPL setup can also be used for your tests. That provides one with the very same tools for developing and debugging your tests, which I’ve found to be really handy. ShadowCLJS provides a test runner, that you can jack up your REPL into.

As said earlier, if you manage to squeeze your view components, event and subscription implementations into pure functions, it makes writing unit tests for them very pleasant. This is also one of the key points of the way that’s the prevailing idea behind in the previous chapters that define an app structure. Having a clear and concise division of responsibilities and strive to boil most things down to pure functions and basic datastructures, at least in my experience, make testing a hell of a lot easier.

Still I think the key selling point for me has been Re-Frame’s testing tools. Time after time I’ve been struggling with E2E tests. The tools change (Cypress, TestCafe and what have you) but the problems still persist. I’ve started to wonder whether the problem isn’t so much that the tools themselves are crap, rather than that they are set up against an impossible foe and used incorrectly.

Consider the following tests that utilizes the Re-Frame’s run-test-sync

(deftest calculation

(rf-test/run-test-sync

(let [current-value (rf/subscribe [calculator-model/current-value])]

(rf/dispatch [calculator-model/reset])

(is (= 0 @current-value) "Initial value should be 0")

(rf/dispatch [calculator-model/append-value 666])

(is (= 666 @current-value) "The new value should be updated")

(rf/dispatch [calculator-model/add])

(rf/dispatch [calculator-model/append-value 1])

(rf/dispatch [calculator-model/evaluate])

(is (= 667 @current-value) "The evaluation should yield expected result"))))

What it does, is that it goes through a basic workflow, where the user would input a value, press the “+” button, add a second value and finally evaluate the whole created clause.

This tool is actually a heck of a powerful one, since it makes it possible to test pretty complex workflows without any dirty meddling with the actual UI just by mutating the state via dispatched events and evaluating how the subscriptions react to those changes. You’re also able to mock any other events in before the body of your run-test-sync making it very easy to mock any IO e.g. HTTP requests, which helps out even more.

In a perfect world, this would leave the E2E tests with merely the responsibility of opening the views and seeing that they don’t catch fire for some obscure reason.

Closing words

This setup still has its pain points especially when it comes to build tools and when you’re “working on the edges of the ecosystem”, e.g. with interop with other JS stuff. For example, I’ve had my fair share of swearing under my breath when fighting with NPM issues.

Though once I’ve gotten past those and been inside the “fluffy functional world”, I found this to be among the least painful SPA setups that I’ve come across.