Prolog is now over 50 years old and most people know it from some university course on logic programming. Despite its relative obscurity outside logic programming Prolog can be used as a general-purpose programming language and implementations exist for most environments (either natively or through JavaScript).

In this post, I will focus on using Definite Clause Grammars (DCGs) for parsing and interpreting a toy Logo-like language for creating programmatic graphics. I will not delve into the background of DCGs. For more information on it, see the Wikipedia page and watch the excellent video on Markus Triska’s The Power of Prolog youtube channel.

In this post, we are using the open-source SWI-Prolog implementation. See the end of the post for a link to the full code.

Say the magic phrase

The main entry point for using DCGs is the phrase predicate. Phrase is the relation between a

grammar body and an input list (and possibly a remaining list). The first argument is the grammar

body and the second argument is the input list (of characters when parsing).

A grammar is defined with the --> syntax:

% Grammar that matches binary trees of integers as lists

tree(empty) --> ".".

tree([Left,Right]) --> branch(Left), ",", branch(Right).

branch(X) --> integer(X) | tree(X).

We can use this grammar against a string to parse it:

?- phrase(tree(T), "((3,(1,.)),(42,666))", Remaining).

T = [[3, [1, empty]], [42, 666]],

Remaining = [] .

We get the tree T with none of the input list remaining, great!

Now we can move to a more substantial grammar.

A toy Logo language

Logo is an educational programming language that many people will remember from turtle graphics. We define a toy Logo-like language that can be used to create graphics programmatically.

Turtle graphics are usually defined by having an implicit current position and direction and issuing commands that move from the current position.

We can define a minimal language with only 4 operations:

- fd (move forward, drawing a line as you go)

- rt (rotate N degrees)

- pen (set the pen color)

- repeat (repeat the given instructions N times)

This language, while not a real programming language yet, is enough to create some interesting images.

Defining the grammar rules

Next, we need to define the nonterminals that make up the grammar of our language.

We start with the topmost rule to parse a list of commands which we will call turtle.

In the rules, comma is read as “and then” and the vertical bar as alternatives.

The blanks rule is any amount of whitespace characters.

turtle([]) --> []. % the empty program

turtle([Cmd|Cmds]) --> blanks, turtle_command(Cmd), blanks, turtle(Cmds).

turtle_command(Cmd) --> fd(Cmd) | rt(Cmd) | pen(Cmd) | repeat(Cmd).

fd(fd(N)) --> "fd", blanks, integer(N).

rt(rt(N)) --> "rt", blanks, integer(N).

pen(pen(R,G,B)) --> "pen", blanks, integer(R), blanks, integer(G), blanks, integer(B).

repeat(repeat(N,Cmds)) --> "repeat", blanks, integer(N), blanks, "[", turtle(Cmds), "]".

This grammar states that a turtle program has possibly some blanks then a command, possibly more blanks, and then more commands. Empty input means an empty list of commands.

Then we define a command as alternatives of the different commands clauses and each command as its own nonterminal. The commands repeat the name because we want to define the Prolog compound terms that make up the parsed data.

We can use this phrase to parse a simple program:

?- phrase(turtle(T), "repeat 5 [ fd 25 rt 144 ]").

T = [repeat(5, [fd(25), rt(144)])] .

Now we can see the parsed representation of the program. We are ready to do something with this program. Can you guess what the above snippet will draw?

Executing the program

The power of DCGs is not limited to just parsing text, but we can model a stateful process by modeling the relationship between the previous state and the next state. We can use the semicontext notation to define the next state as the remaining list. The semicontext notation allows us to pass arguments implicitly (like monads).

When executing a program we need some context. In this case, we need the current position of our “turtle” (X, Y), the color of the pen, and the current angle the turtle is facing.

We can model this state as a compound term of t(X,Y,Color,Ang).

Then we have to define the grammar rules for the commands. For this example, I will use HTML Canvas

element 2D context to draw the picture.

% Basic DCG state helper nonterminals

state(S), [S] --> [S].

state(S0, S), [S] --> [S0].

eval_all([]) --> [].

eval_all([Cmd|Cmds]) -->

eval(Cmd),

eval_all(Cmds).

eval(fd(N)) -->

% Previous state to new state

state(t(X1,Y1,C,Ang), t(X2,Y2,C,Ang)),

{ Rad is Ang * pi/180,

X2 is X1 + N * cos(Rad),

Y2 is Y1 + N * sin(Rad),

% Call JS interop on the JS global CTX

_ := 'CTX'.beginPath(),

_ := setcolor(C),

_ := 'CTX'.moveTo(X1,Y1),

_ := 'CTX'.lineTo(X2,Y2),

_ := 'CTX'.stroke()

}.

eval(rt(N)) -->

state(t(X,Y,C,Ang1), t(X,Y,C,Ang2)),

{ Ang2 is (Ang1 + N) mod 360 }.

eval(pen(R,G,B)) -->

state(t(X,Y,_,Ang), t(X,Y,[R,G,B],Ang)).

eval(repeat(0,_)) --> [].

eval(repeat(N,Cmds)) -->

eval_all(Cmds),

{ N1 is N - 1 },

eval(repeat(N1, Cmds)).

Above we are defining nonterminals for evaluating the commands. We evaluate the list in

order and define a separate clause for each of the commands. The fd is the most involved

one as it does some JS interop to call <canvas> element context (which we define on the

host HTML page).

The pen and rt just define the relationship between the previous and next states. Even without any mutable state, the code looks quite nice and simple.

%% The final piece, tying it all together... this is called from our JS page

run(ProgramString) :-

phrase(turtle(T), ProgramString),

phrase(eval_all(T), [t(160,100,[0, 200, 0],0)], [FinalState]).

With this final piece, we have all the Prolog code we need. We still need a host page to load our Prolog system and code into an HTML page. That code is available here.

Now we are ready to run our program example from before. Did you guess what it is?

Yes, you guessed correctly, you get a star!

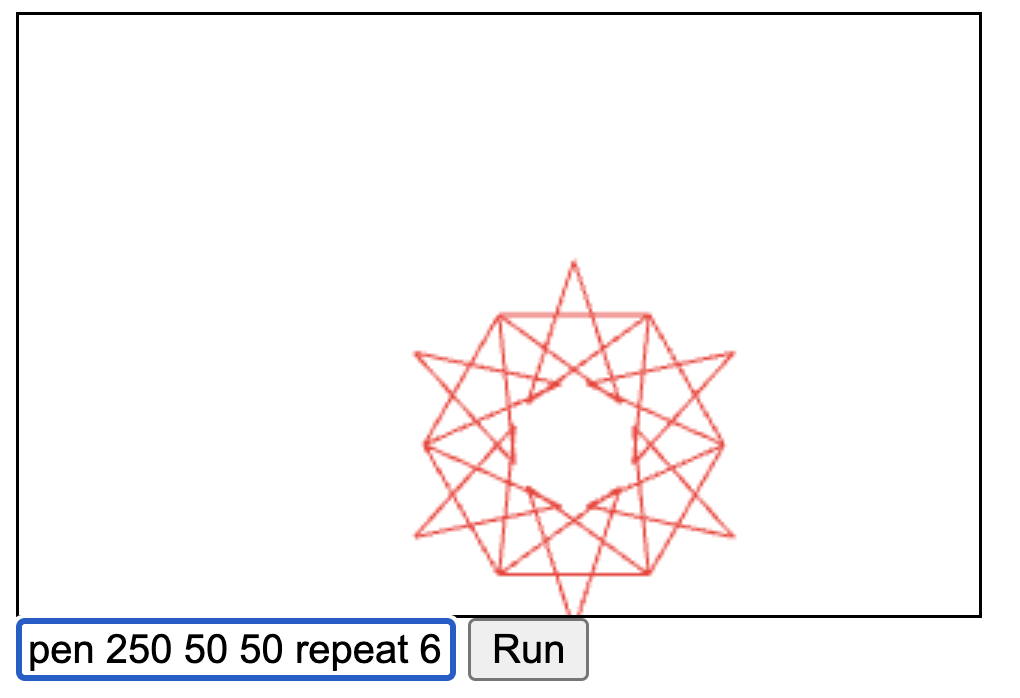

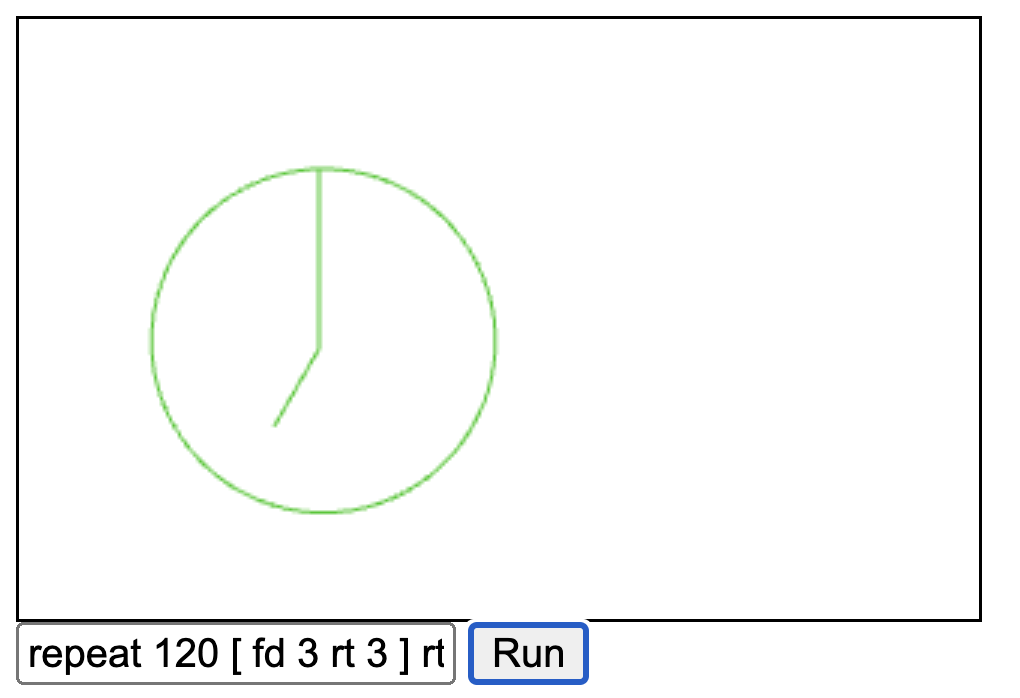

Here are a couple of more examples:

A circle of stars:

pen 250 50 50 repeat 6 [ repeat 5 [ fd 50 rt 144 ] fd 50 rt 60]

A minimalist clock face:

repeat 120 [ fd 3 rt 3 ] rt 90 fd 60 rt 30 fd 30

Further work and conclusions

In this post, we created a simple parser and interpreter for a toy Logo-like language.

You could easily add more commands and programming language features (like variables and

arithmetic expressions) to make it more like a “real” programming language. We also didn’t

do any error handling. Any parse syntax errors will just fail the run goal.

Another avenue of extension would be making the interpretation more abstract. You could give a template goal to do the actual drawing. This way you could extend to different rendering engines like SVG elements or PDFs.

But even as it stands, this hopefully shows that DCGs are a very powerful feature of Prolog.

In this post, we used SWI-Prolog WASM build and its JS interop features. There are also other implementations that can be used in the browser, especially Tau Prolog which is written in JavaScript. Some details of the interop and DCG libraries differ between implementations, so check the documentation.