Identification of an entity

Every developer who has worked with databases, and actually with code in general, knows how important entity identification is. The id of a piece of data, may it be a class instance in memory or a database row, identifies if something is the same as something else. As a java coder, the equals and hashcode are close to my heart :). In DB context the id tells you what data to fetch from the database and where to write an update of the data.

I’d like you to imagine a scenario where you wouldn’t have this information. How would you update data into a database? How would you fetch a certain piece of data for presentation? You might be thinking “But Henri I do have the ids, why wouldn’t I ?”. One example could be that the data is produced by an analog process like paper forms, yes those do still exist. You then would have to somehow determine if the information in the form matches something in the database or is it something new.

This is a hard problem and the internet and science community has many possible solutions from machine learning to many different algorithms. In this blog, I’ll demonstrate one solution that is based on the Fellegi-Sunter probabilistic method. The method calculates a probability that some piece of data is actually the same entity as some other piece of data. The main points I’ll cover are the algorithm and performance implications in a simulated real-world scenario.

Probabilistic linking

Probabilistic linking, as the name implies, is based on probabilities. This means that a piece of data X is compared against multiple possible matches Y and a probability is calculated for if the X and Y are a match.

The input for the algorithm is the entity attributes and a match probability m and non-match probability u for each attribute. If an attribute is a match, say X.name == Y.name, we use the match and non-match weights with the following formula.

I’m using natural logarithm but some implementations use log2, it slightly modifies the curve and affects the maximum and minimum values but the end results are quite similar.

If X.name != Y.name is not a match we use the non-match formula

So how do different matching and non-matching probabilities affect a single attribute’s calculated weight. If the attribute is a match the effect of different weights is depicted in the following 3d mesh with the m and u values ranging from 0..1 (figures are generated with Octave, high recommendations for it for mathematical analysis)

If the attribute is not a match the weights act like this

So it’s obvious that if the attribute is a match, high match probability combined with low non-match probability gives higher weight. For a non-matching attribute, it’s reverse. Note also that the weight might be negative ranging from -3..3.

For calculating the total weight for the probability the calculus is done for each attribute in the entity and then all of the weight values are summed together. In Kotlin code this might look something like this for an entity called Demography

data class Demography(val id: Long?, val address: String, val city: String,

val firstname: String, val lastname: String,

val postalcode: Int, val birthday: LocalDate)

fun <T> defaultMatcher (a:T, b:T) : Boolean = a == b

fun fuzzyStringMatcher (a: String, b: String) : Boolean = FuzzySearch.ratio(a, b) > 60

data class FieldWeight<DT, T>(

val field: (DT) -> T, // Function to get the attribute value from object instance

val matchProbability: Double,

val nonMatchProbability: Double,

val matcher: (a: T, b: T) -> Boolean = ::defaultMatcher

)

private val fields = setOf(

FieldWeight(

Demography::firstname,

0.99,

0.3,

::fuzzyStringMatcher

),

FieldWeight(

Demography::address,

0.6,

0.5

),

FieldWeight(

Demography::city,

0.7,

0.4

),

// ... and so on ...

)

fun calculateForEntity(X: Demography, Y: Demography) : Double {

return (fields.map {

calculateSingle(it, X, Y)

} ).reduce { acc, d -> acc + d }

}

private fun <DT, T> calculateSingle(

fieldWeight: FieldWeight<DT, T>,

X: DT,

Y: DT

): Double {

val a = fieldWeight.field(X)

val b = fieldWeight.field(Y)

return if (fieldWeight.matcher(a, b)) {

ln(fieldWeight.matchProbability / fieldWeight.nonMatchProbability)

} else {

ln((1 - fieldWeight.matchProbability) / (1 - fieldWeight.nonMatchProbability))

}

}

I’m using fuzzy matching for some attributes. This takes care of possible typos in the manual process, in my case, it’s very common that my first name is typed Henry and not Henri. For fuzzy string matching, I’m using https://github.com/willowtreeapps/fuzzywuzzy-kotlin library and a hard-coded likeness of 60. Yes, the value is a pure guess and has no scientific meaning.

Matching faster than tinder

To test the matching in a simulated real-world scenario I need some data. I’ll use PostgreSQL DB running in a docker container on my laptop as the data storage. For generating data I’m going to use Kotlin and a faker library https://github.com/serpro69/kotlin-faker. The data structure will be the demography class shown in the previous chapter. I’ll generate two and a half million rows into the DB for this real-world scenario.

I now have the algorithm implementation and data in the DB. The next step is to fetch the data and run it through the algorithm. It’s quite obvious there are some performance considerations as we need to match a single record against 2,5 million rows from the DB. I’ll start with a naive approach that just loads everything from the DB and feeds it to the algorithm. We shouldn’t pre-optimize before we actually know there is a need for it.

// -------- DB query --------

fun findAll(): List<Demography> = db.findAll(Demography::class.java,

"""select id, address, city, firstname, lastname, postalcode, birthday from demography""".trimIndent())

/* --------

Algorithm execution,

filtering lower than 2 weights for more efficient sorting

-------- */

fun sort(demo: Demography, toCompare: List<Demography>) : List<Pair<Demography, Double>> {

return toCompare.map {

it to calculateForEntity(demo, it)

}.filter { it.second > 2 }.sortedByDescending { it.second }

}

// -------- The test --------

val exact = Demography(

id=null,

address="Apt. 719 Manninengatan 51, Lakano, NC 96443",

city="Niahe",

firstname="Laura",

lastname="Mäkinen",

postalcode=16660, birthday=LocalDate.of(2021, 8, 12)

)

fun testLinking() {

val now = System.currentTimeMillis();

val all = demographyDao.findAll()

println("Loaded DB rows in ${System.currentTimeMillis() - now}ms")

DemographySpec.sort(exact, all).take(10).forEachIndexed { index, pair ->

println("Matched at $index to \n ${pair.first} \n with score ${pair.second} ")

}

println("Found matches in ${System.currentTimeMillis() - now}ms")

}

The output of this looks like this

Loaded DB rows in 4592ms

Matched at 0 to

Demography(id=961344, address=Apt. 719 Manninengatan 51, Lakano, NC 96443, city=Niahe, firstname=Laura, lastname=Mäkinen, postalcode=16660, birthday=2021-08-12)

with score 8.19490576105457

Matched at 1 to

Demography(id=2270654, address=Suite 591 Leinonenkatu 901, Raahe, NV 15313, city=Niahe, firstname=Lauri, lastname=Jokinen, postalcode=47755, birthday=2021-08-12)

with score 5.555848431439312

Matched at 2 to

Demography(id=699265, address=Apt. 321 Toivonengatan 9, Rauma, KY 60244, city=Oruma, firstname=Laura, lastname=Väisänen, postalcode=60325, birthday=2021-08-12)

with score 4.708550571052109

.....

Found matches in 11311ms

From this, I can see that the DB operation (query execution and data serialization) takes 4,5 seconds and running the algorithm around 7 seconds. Let’s try to optimize this a bit. First I’ll use streaming for loading data from the DB

// Streaming using Kotlin sequences

fun findAllStreaming(): Sequence<Demography> {

return streamQuery().asSequence()

}

// Streaming using Java streams

fun findAllStreamingJava(): Stream<Demography> {

return streamQuery()

private fun streamQuery() = jdbcTemplate.queryForStream(

"""select id, address, city, firstname, lastname, postalcode, birthday from demography""".trimIndent()

) { rs, _ ->

Demography(

id = rs.getLong("id"),

firstname = rs.getString("firstname"),

lastname = rs.getString("lastname"),

birthday = rs.getDate("birthday").toLocalDate(),

address = rs.getString("address"),

city = rs.getString("city"),

postalcode = rs.getInt("postalcode"),

probability = null

)

}

and then run the algorithm parallel with Java’s parallels streaming.

private val scheduler = ForkJoinPool(16)

fun sortParallelJava(demo: Demography, toCompare: Stream<Demography>) : List<Pair<Demography, Double>> {

return scheduler.submit<List<Pair<Demography, Double>>> {

toCompare.parallel().map {

it to calculateForEntity(demo, it)

}.filter { it.second > 2 }.sorted { o1, o2 -> o2.second.compareTo(o1.second) }

.collect(Collectors.toList())

}.get()

}

The result

DB query took 1866ms

.....

Found matches in 10683ms

Well, that didn’t really do much as a whole. It seems that the actual DB side of the query doesn’t take that much time. Let’s analyze the time taken by each step a little closer. It would seem the data serialization might take a considerable amount of time so let’s measure it.

val now = System.currentTimeMillis();

val demos = demographyDao.findAllStreaming()

println("DB query took ${System.currentTimeMillis() - now}ms")

val demosList = demos.toList()

println("Serialization took ${System.currentTimeMillis() - queryDone}ms")

DB query took 1740ms

Serialization took 2733ms

So it’s obvious that the serialization of the DB query results takes a lot of time. My guess is that this might cause problems for the parallel execution of the sorting as well. I’ll try to use the serialized in-memory list and run the algorithm against this it with the same parallel processing.

Algorithm took 690ms

Found matches in 5163ms

That’s a real performance gain. The downside, it takes 3 GB of memory as we load everything into memory. It’s is the traditional trade-off of CPU vs. memory, that we’re dealing with here. As the critical part is the running time the memory requirement is not that bad. It will be quite restrictive on the amount of parallel matching process we can run at any given time. That of course can be handled in a cloud environment with auto-scaling and queues, but there must still be something I can do. As most of the time is taken by transferring the data from the DB to memory for the algorithm, the obvious solution is not to transfer the data at all and execute everything in the database.

Running matching logic in the DB

All the necessary pieces that we need to execute the matching logic completely in the DB are available in PostgreSQL

- A conditional operation to determine if to use the matching or non-matching function for an attribute. PostgreSQL conditional

- Fuzzy matching for strings PostgreSQL fuzzystrmatch

- Basic sorting SQL order by

So the SQL for a static entity matching would be like this

CREATE EXTENSION fuzzystrmatch;

select d.*,

(

case when levenshtein(d.firstname, 'Heikki') < 2 then ln(0.9 / 0.3)

else ln((1 - 0.9) /(1 - 0.3)) end +

case when levenshtein(d.lastname, 'Nieminen') < 2 then ln(0.7 / 0.5)

else ln((1 - 0.7) /(1 - 0.5)) end +

case when d.address = 'Savolainengatan 370, Haapesi, TX 41036' then ln(0.9 / 0.3)

else ln((1 - 0.9) /(1 - 0.3)) end +

case when d.city = 'Lakano' then ln(0.7 / 0.6)

else ln((1 - 0.7) /(1 - 0.6)) end +

case when d.birthday = '2021-03-30' then ln(0.99 / 0.1)

else ln((1 - 0.99) /(1 - 0.1)) end +

case when d.postalcode = 98986 then ln(0.7 / 0.3)

else ln((1 - 0.7) /(1 - 0.3)) end

) as probability

from demography as d order by probability desc limit 10

I’m using levenshtein distance for the fuzzy matching since soundex and metaphone are little tricky for a non english languages. The SQL doesn’t look that bad but it’s just a static test to check how the query should look like. I still need to pass the attributes and their weights to it as parameters so the implementation can work with different data sets. For this I added a helper data class QueryWeight and generate the SQL with a string manipulation.

data class QueryWeight<T>(val matchProbability : Double,

val mismatchProbability : Double,

val value: T, // value to test against

val field: String,

val fuzzyTarget : Int = 0)

fun sortInDB(weights : List<QueryWeight<*>>) : List<Demography> {

val params = weights.flatMap {

listOf (

it.field to it.value,

it.field + "Pos" to it.matchProbability,

it.field + "Neg" to it.mismatchProbability

)

}.associate { it.first to it.second }

val generatedWeights = weights.mapIndexed { index, queryWeight ->

val q = if(queryWeight.fuzzyTarget != 0) {

""" case when levenshtein(d.${queryWeight.field}, :${queryWeight.field})

< ${queryWeight.fuzzyTarget} then ln(:${queryWeight.field}Pos / :${queryWeight.field}Neg)

else ln((1 - :${queryWeight.field}Pos) / (1 - :${queryWeight.field}Neg)) end

""".trimIndent()

} else {

""" case when d.${queryWeight.field} = :${queryWeight.field}

then ln(:${queryWeight.field}Pos / :${queryWeight.field}Neg)

else ln((1 - :${queryWeight.field}Pos) / (1 - :${queryWeight.field}Neg)) end

""".trimIndent()

}

q + if(index == weights.size - 1) "" else " + "

}.reduce { acc, s -> acc + s }

return db.findAll(Demography::class.java, SqlQuery.namedQuery(

"""select d.id, d.address, d.city, d.firstname, d.lastname, d.postalcode, d.birthday,

( """ + generatedWeights + """ ) as probability

from demography as d order by probability desc limit 10

""".trimIndent(),

params)

)

}

I must admit the SQL generation function is kind of horrible but it serves its purpose for this demonstration. So how about the performance

Found matches in 826ms

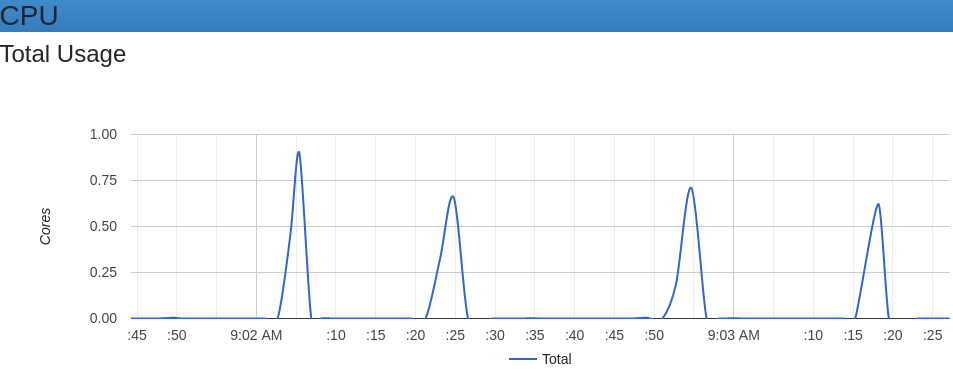

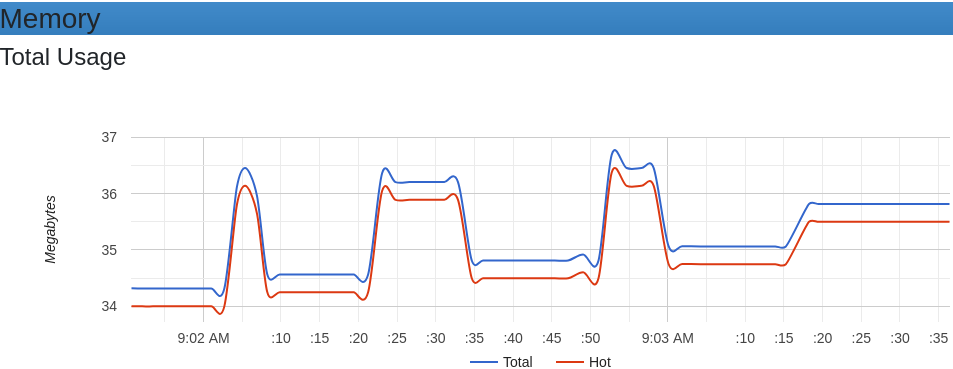

That’s quite the improvement and the memory usage is non-existent when compared to the 3 GB of the previous tries. I’ve logged the memory and CPU usage of the postgres docker image with googles cAdvisor and there really is not a lot difference between the four different versions I tried.

Using the DB for the whole process is the way to go.

Actual entity matching results

Now that I have a good way to run the matching algorithm and a lot of testing data it is a good time to actually see if I can match some entities. Let’s first try with an exact match. I also added percentages for probability by calculating the maximum and minimum possible values and comparing the weight in that scale.

// ----- The weights to use for the fields ------

fun generateDBWeights(testAgainst: Demography): List<DemographyDao.QueryWeight<out Any>> {

return listOf(

DemographyDao.QueryWeight(0.6, 0.5, testAgainst.address, "address"),

DemographyDao.QueryWeight(0.7, 0.4, testAgainst.city, "city"),

DemographyDao.QueryWeight(0.99, 0.3, testAgainst.firstname, "firstname", 2),

DemographyDao.QueryWeight(0.99, 0.1, testAgainst.lastname, "lastname", 2),

DemographyDao.QueryWeight(0.8, 0.3, testAgainst.postalcode, "postalcode"),

DemographyDao.QueryWeight(0.99, 0.20, testAgainst.birthday, "birthday"),

)

}

val toTestAgainst = Demography(

id = null,

address="Niemiranta 935, Kauinen, MT 19157",

city="Hemina",

firstname="Henrik",

lastname="Laitinen",

postalcode=41248,

birthday=LocalDate.of(2021, 8, 31),

probability = null

)

/* ----- Results ------

Matched at 0

Demography(id=725814, address=Niemiranta 935, Kauinen, MT 19157, city=Hemina, firstname=Henrik, lastname=Laitinen, postalcode=41248, birthday=2021-08-31, probability=6.80861139993468)

with probability of 100.0%

Matched at 1

Demography(id=913919, address=Lehtogatan 0, Lainen, NE 82349, city=Orinen, firstname=Henrik, lastname=Lahtinen, postalcode=64548, birthday=2021-08-31, probability=2.916791101824054)

with probability of 82.39632310340626%

Matched at 2

Demography(id=18583, address=Mattilakatu 510, Rainen, GA 25052, city=Rainen, firstname=Henrik, lastname=Laitinen, postalcode=80015, birthday=2021-08-31, probability=2.916791101824054)

with probability of 82.39632310340626%

Matched at 3

*/

The algorithm seems to work with an exact match. Let’s try with the wrong address and postal code. The results are the same but the probability for the number one candidate is down to 88.06288343665607%. As the attribute count is quite low the granularity of the probabilities is quite coarse. With more attributes, there would be more differences between the entities. Also in a real solution, it’s possible to use human input with the sorted entities to select the right one and if the probability of a match is very high do the linking automatically.

When it comes to the field match and non-match probabilities, I can only say the age-old proverb that it depends on the use-case. The values should come from the domain knowledge. For example, we might know that in our process the birthday is quite often right so we would give that a high matching probability and low non-matching probability. Tweaking the probabilities is an incremental process that greatly benefits from testing and simulation.

As for the fuzzy matching with Levenshtein, it corrects possible typos in the name but it might cause wrong results. Care needs to be taken with the distance selection, as a large distance will match with wrong names. For example Anni and Antti have only Levenshtein difference of 2.

Final thoughts

Mathematically calculating probabilities can provide help in situations when we must find out if something matches something else. It’s definitely not a silver bullet but a tool that can be used in combination with human input. The implications might be that we can offer a better user experience for the end-users and faster throughput times for the workflows. As a coder, the notion of doing entity linking without an exact id is a little bit scary but as a complementary action, I can see many use cases for it.

On the performance side, it still stands that don’t optimize if it’s not needed and data transfer is costly.

Thanks for reading.