I once told my mother-in-law (who is not a coder) that I had dreams about programming when I started with a new project. She looked astonished and asked: “You had a dream that you were sitting at the computer?” Programming doesn’t feel like just sitting at the computer. In this post, I want to express some of my emotions related to coding and explore some common emotional phenomena that have come up in discussions with fellow coders.

Emotional roller coaster

Programming is similar to any other creative task and especially writing. At least for me, it is often painful. It can be hard to get started writing a new feature. Personally, I find it hard to write throwaway code and make prototypes. I’d like everything to be clearly named and precisely typed from the start. Despite that, often, the cure to programmer’s block is to find something tiny you can implement and write that, just to get started. Writing is often painful, but it can also be exhilarating. Sometimes you write elegant, clean code that works, or just have fun exploring different options.

More than any other creative activity, programming can have a roller-coaster-like emotional quality. The high of finding a solution can be incredible, but it can change into frustration or even panic in the next moment. When I first started studying programming, I had a hard time controlling my negative emotions, mostly frustration. Getting more experience helped, and I also learned to take a break or ask for help if I became too frustrated. Often, after a short break, your head is clearer, and the problem seems a lot clearer also.

When I started working as a programmer professionally, I got access to production environments, which added panic to my emotional repertoire at work. Sometimes you do something to the production server that you really didn’t mean to. Of course, the best way to avoid these situations is to have transparent processes and avoid ad-hoc tampering in the production environment. It is also essential to try to stay calm and, if possible, ask for help and admit your mistake.

Addicted to the flow

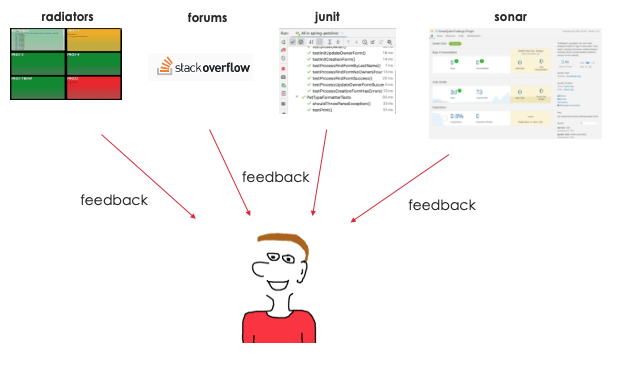

Programming can be a very addicting activity. Almost all coders I’ve talked to recognize the addicting flow state when the task is within the sweet-spot of your skill-level. It gives you enough challenge to be exciting and also allows you to go forward with it steadily. My colleague Janne Rintanen pointed out in his Dev Day talk that programming is so fun and rewarding because you get constant feedback on your work. When a test fails, you fix it, and you get a green light in your IDE. Or when a smoke test fails, and a radiator goes red, you solve the problem, and you get a green light. You also do code reviews and get a lot more personal feedback than in many other jobs. I personally recognize this to be one of the reasons I enjoy software development so much.

Image by Janne Rintanen

Going into a pleasant flow state while coding is a somewhat controversial subject. Flow state has been shown to correlate with high performance and positively affect life satisfaction. Some people, like Robert Martin, warn against it, though. In his book Clean Coder, he states that the flow state is just a mildly meditative state in which rational faculties are diminished. I think there is the right time and place for both flow and non-flow states while programming. When requirements are exact, and there are no significant architectural considerations to make, it can be very productive to type away a few features in a pleasant flow state. When you need to try a few approaches to see what works for the user or do a significant refactoring of the code, the flow state is not necessarily useful.

Becoming addicted to solving a problem can be unproductive from another viewpoint too. I have often been really invested in finding a solution to a bug and had a feeling of being on the verge of resolving it (sometimes for hours). I have been afraid of taking the smallest break for losing track of the carefully adjusted thoughts in my head. But then, after finally taking the break, I have seen the problem in a completely new light and have been able to solve it much faster. Similarly, sometimes a weekend spent away from the code provides new insight on Monday.

Let it go, let it go

Another cognitive or emotional pitfall is to fall in love with your work. A programmer must strive to view their work as objectively as possible and be ready to discard stuff that no longer works. This is a sunk cost fallacy, in a way. I might think that a component I wrote works well enough because I have written it. You might see the situation more clearly because you haven’t invested any time developing the component, and you might think the component should be discarded and completely rewritten.

I have learned to manage this bias better, but sometimes I still feel a sting when I have to discard some code I really liked. Sometimes, though, it can be a relief to get rid of code I wasn’t very proud of in the first place… Maybe we could approach this situation like Marie Kondo: thank the code for the fun we had and things we learned while writing it and then delete it.

The interpersonal stuff

More often than not, programming is not a solitary activity. I feel most fulfilled at my job when I see a feature I developed being actually useful to someone and making their life a bit easier. Often, we also write code not only for our eyes but for other developers. That brings pride, shame, and competition into the picture. It can help to learn not to take yourself so seriously and to laugh at your own mistakes. Sometimes the code you wrote three weeks ago can be the funniest material.

Navigating the social environment of software development and related emotions can be demanding. It is essential to learn to manage the expectations of yourself and others. It is easier to avoid stress and anxiety if you can avoid overpromising with schedules. This is easier said than done, though. I have found that estimating work accurately can be more complicated than most daily programming tasks. Generally, it is better to overestimate the time needed, just a little bit, to accommodate for unexpected difficulties.

Impostor syndrome is widespread among developers, as with any high-skilled professions. There are estimates that 70% of people suffer from impostor syndrome at some point in their lives. I feel like an impostor every time I do something new. Like right now, writing my first blog post. Recognizing the phenomenon and experiencing it all over again has helped me to deal with it. My brain often tells me that I’m in the wrong place and don’t know how to do the things expected of me, but I have solved many difficult situations despite that. It also helps to realize that not knowing something is not proof that your intelligence has reached its limits but an opportunity to expand your knowledge and experience.

Conclusion

A programmer probably experiences a lot of similar feelings than anyone doing cognitively demanding creative work. It can be very frustrating, slow, and painful. And it can be fun and gratifying. On the other hand, software development probably is a lot more addictive than many other creative tasks because of constant feedback. Making something that works and helps other people feels great.