Cloud platforms are magnificent. For anyone who used to create or operate software running in a traditional on-premises server room, they offer incredible speed in getting ideas to production, and experimentation with new things. However, this speed comes with a cost: Sometimes that cost is money, as AWS bills can sneak up on you. Sometimes the cost may be a bad architecture that gets more expensive as you progress, a badly compromised security that makes you vulnerable for many new attack vectors - or it can be that you are paying for lots of new services just because you can - without getting the benefits you were looking for.

In this article, I’m going to go through some of the worst mistakes that might happen when you start working on the AWS platform. These mistakes are based on both personal experience, aka my mistakes, and things I’ve seen, aka other people’s mistakes. I will also try to provide some insights into why we need to pay attention here, and what could we do to avoid the negative impact while benefiting from the newfound speed and agility. I’ve been working pretty much in cloud and serverless for the last five years, before that I had a lot of on-premises experience. I’m most well versed with AWS architecture and best practices, but most of these thoughts will probably apply also to Azure and Google Cloud Platform projects.

So who should read this? Whoever feels responsibility for success. Many of these are details that simply are not easy to see, measure, or control on too high a level. And if they are governed, it typically makes development very slow and rigid, losing the benefits of using the cloud in the first place. So this advice is mostly geared for those who are kickstarting a very fast-moving project without much governance or wish to handle these concerns within the project. Or for those who wish to have an understanding of the concerns and some offering of solutions for them, when having those conversations.

Antipattern #1: Too wide permissions

Normal on-premises systems use firewalls and isolation maintained by network administrators between separate servers and applications, to try and limit accidental access. Or they might not. On the other hand, building and combining services in a cloud environment, there might not be any protection in place, unless you build it yourself. And sadly every AWS tutorial and video training course online tends to do the examples by giving full and wide access for any services that are used - for speed and convenience. And this is exactly the first antipattern we want to shut down.

If a user or a service has access to this policy, they are allowed to do anything to everything, including creating, changing, deleting the resources, covering their tracks, etc. Furthermore, this kind of policy does nothing to document what that service or user is actually dependent on, what it needs to work. It’s a lazy and extremely dangerous way of declaring the permissions.

The wider concept here is to minimize the blast radius. And we do that with the Principle of Least Permission (POLP). Blast radius means an area of services and infrastructure that may be affected if a security breach or misconfiguration takes place. In other words, if your Lambda function has full access to anything in the account, and it gets compromised, damage can be horrendous. Also, if anyone is auditing your solution, this mess will be revealed and require actions to fix.

See: Permission boundaries for IAM entities.

In this example, we are limiting the allowed actions a bit, but they can still be targeted towards ANY bucket in the system, not just the expected ones. Any bucket that now exists, or will be created in the future. This is of course okay when you need to do that, but often you will only be accessing a single bucket instead, or a few of them.

Symptoms of too wide a blast radius are:

- AWS Policies with a lot of asterisks giving wide or unlimited access to services, or resources

- AWS Roles using built-in system policies with FullAccess permissions

- Developers doing their daily work with credentials that use similarly unlimited policies

- No network isolation, everything in one network

So, how do you fix this? Well, you invest some time, effort, and perspiration. You create those boundaries and walls. You create minimal permissions that are required to do the task. If you create them in a good manner, they do not limit the valid uses of software, but they limit the damage if an ‘explosion’ happens within. They limit the width of a potential exploit. They also document what parts of services you are using. These boundaries are much cheaper and easier to create while building the solution, and they can be costly to fix afterward. So the second your POC grows to an MVP, and you start doing implementation sprints, you should start doing the POLP dance, including it in the code and review workflow.

There are some tools also to help with this, that can review the templates or policies, and alert if they seem a bit too wide. For example, AWS has services like IAM access advisor, or AWS Trusted Advisor/AWS Organizations can be used to audit this constantly yourself. I’ve also had success with tools such as CFRipper. There are also plenty of commercial tools if you wish to go that route. You can run these as part of your build, or set up a CloudFormation event-triggered Lambda function that can stop deployment if the quality gate is not passed. With good tools, it’s possible to create exceptions to rules or modify and evolve the rules yourself. But a good tool is also cost-effective and cheap. If you introduce some automation in your development process, this cleanup and tightening are automatically done when it’s the cheapest.

Antipattern #2: Manual work on AWS console

Manual work in our field is most of the time an antipattern. Manual work implies that it’s done by humans in a variety of conditions, and results may vary as well. Manual work also implies that if the one who knows how to do this is not present, nothing will happen, so there’s a severe bus factor included. Manual work may also be delayed, a lot. And while manual work can be made better with good, up-to-date, precise documentation on the process and steps, if such exists, I have yet to see it - at least as the project has been running for longer than a year. It also implies replicating those environments might be difficult and at least costly.

Manual work is especially error-prone when something breaks badly and people are under pressure to fix it, or stressed, or hungry, or thinking of their upcoming vacation.. I think you got the point.

Specific to cloud environments, manual work also implies that developer accounts have and need to have wide access to APIs and services underneath. And it implies that when they make a human mistake, such as dropping a database in the wrong environment, because they had one too few cups of coffee in the morning, the results can be immediate and irreplaceable.

The cure for all of this is to automate, follow the Infrastructure as Code (IaC) principle. By creating any resources by code instead of manual work, we gain a lot of good things:

- Of course, if you use code to create resources, it becomes an exact, repeatable process.

- So if you want to recreate your resources because of a need to migrate, or experiment with a copy of the original environment, or simply create separate copies of DEV, TEST, QA, UAT, PRODUCTION environments, you just run the same scripts.

- It means your environments do not become unique snowflakes where test environments are so different that they don’t represent production anymore - but identical copies that may be nuked and recreated in hours if necessary

- This also means your disaster recovery plan has a good solid foundation: You just need to take care of the backups too

- It also means cleanup becomes easy: You have a manifest of all resources, so if you need to remove them, you have a solid starting point

- IaC means that your infrastructure is also documented, so you don’t need to try to find the service inventories from depts of AWS console

- This also means that sometimes you can also visualize the architecture based on the templates, using 3rd party tools

- IaC means infrastructure changes can also be part of peer review, validation, automated audits, etc, everytime they change

- You can put them in the version control, so they are properly backed up, you can branch and merge changes, and go back to old versions when needed

Good ways to automate the creation of infrastructure and services include (but are not limited to) CloudFormation, CDK, Terraform (which also support many other vendors), I’ve also used Troposphere and Sceptre for AWS. There’s a lot of choices, they all come with pros and cons, so you need to pick up what makes sense to you and stick to it. But as long as you are using ANY of them, you are in a much better place already. You could even use command-line client and bash scripts if you want to, or raw Python and an SDK. But the real solutions designed for this are typically better.

Then why is this an antipattern? Isn’t this obvious? Isn’t everybody already doing this?

Well sadly, no. Because there’s some effort involved. And because many cloud-related things may begin as small quick-and-dirty prototypes, until the momentum catches up and they grow bigger and go into production. In my career, I’ve been called a few times to salvage or ‘productize’ such a project. And let me tell you, it’s much more expensive done after than if it was built in from the very beginning.

When you use automation to create the resources, you naturally want to also automate the running of those scripts, so that it does not require a magically configured unique developer laptop, but can be triggered as Jenkins Pipeline/Github Actions/CodePipeline jobs. Remember, we want a very boring repeatable process. If it’s very boring we’ve done an extremely stellar job, and can make changes to the production environment multiple times a day without things getting any more exciting - in a bad way.

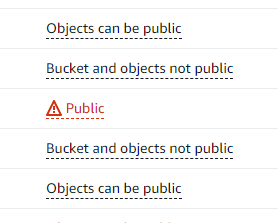

Antipattern #3: Misconfigured S3 buckets

Security Misconfiguration is one of the largest potential vulnerabilities of cloud platforms. It means that instead of only concentrating on OWASP TOP 10 attack vectors and vulnerabilities within code, we need to also consider infrastructure around the code, especially serverless components.

With AWS, I’ve seen most security breach related news with S3 buckets, that have been used carelessly, and accidentally been left open for the whole world to discover. This may happen very easily since there can potentially be just one innocent question or toggle. And if you don’t know the jargon or effects of those choices very well, one can accidentally expose the bucket and all the data, even give permissions to modify or remove it for everyone. And once you expose it to the Internet, it’s only a matter of time until someone finds it. Then if they are evil enough, they do not vandalize it, but silently grab what they can now and in the future, and see if they can use this as a foothold to go deeper.

So let’s not do that. Protecting against misconfigured buckets is easy, there are many ways to do that. If you implement multiple ways, odds are you should be good.

- Education. Have teams that know what they are doing. AWS Certificates are a good way to guarantee a basic level of knowledge. If they are not on the level, make sure they can self-educate themselves, there’s plenty of information available, starting from AWS’s resources. Already reading this blog you have started that path, reading the links at the end is a good next step :)

- Policies. If you are not supposed to be dealing with open S3 buckets within your account, set up an account-wide policy to not allow that. Or leverage fixes for antipatterns #1 and #2: auto-audit your templates, and deny changes if they conflict with the policies. If you need to use also public buckets, pay extra attention to those, and see if you can make it rather an exception than a general approach.

- AWS also has some built-in audit tools that are sensitive to especially AWS S3 buckets, for example, AWS Trusted Advisor, AWS Security Advisor, or AWS Config.

- Also, speaking of policies, note that bucket policies can also accidentally compromise you to a wider audience than intended, or give too much power for access. So as said, be extra careful with these. Peer review them, validate and audit the policies with any tools you have, test them carefully.

While at this antipattern, you can also take a look if there are other things you should immediately build in. AWS Buckets have marvelous support for encryption at rest, automated audit trails, cross-region replication to have better disaster recovery, versioning to have faster disaster recovery, lifecycle policies to take care of data you don’t need anymore. I’ve seen so many buckets used simply as a forgotten data dump, but since these are among the best serverless resources when used right, please use them right. :)

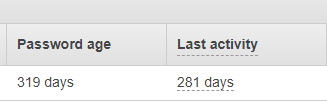

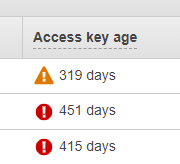

Antipattern #4: IAM users without user lifecycle management

IAM users may not be a horrible antipattern in themselves, after all, IAM is just a built-in access-control mechanism for AWS that you can use as a service. However, if your authentication and authorization model is based solely on IAM users, it does raise some concerns.

- How are the users created, and who can create them? More importantly, how are they removed, when a user does not need access anymore? Do we leave users with God-permissions in the system long after their part in the project officially ended? Because that’s often what happens. It’s easy to create users, but harder to remember to 100% clean them up once they are not needed anymore.

- How are their permissions decided? Are they given by a busy developer who would rather be coding? Are they uniform across the accounts, or unique snowflakes, each one different, permission boundaries defined by how loudly they demanded access?

- How are the passwords rotated? Any policies for password length? Asking because if developers are tasked to create the account, they might not have the incentive to follow up on these, make sure they are secure, and keep them secure. Probably the password is going to be ‘changeme’ in that case, forever.

So mainly I’m pointing out that while technically IAM users are not bad, they become horrible if not maintained, or if maintained half-heartedly. For this reason, most organizations like to integrate some well-maintained user directory to AWS, directory such as Azure AD. This means that user roles and lifecycles are already taken care of, and the project team just has to map them to roles they can assume, and their permissions. That being said, IAM users have some perfectly valid use cases, such as bot users (Jenkins) that need to access

Most big organizations already are doing this quite right, because they understand what happens if this is not done right, and have the proper infrastructure and organization in place for centralized user account management.

So this antipattern and corresponding fixes are mostly for those POCs and MVPs and startup projects that are created with someone’s credit card. If there’s an obvious hole in the system, this is one of the areas where it happens if not done right.

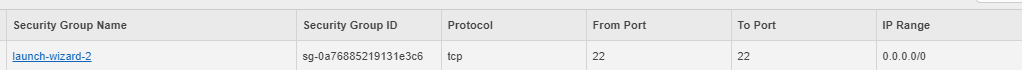

Antipattern #5: Misconfigured networks

This is more akin to the traditional wisdom, also related to the blast radius discussed earlier. If you put all your resources in the same network, which is what is again shown in many tutorials, and often done when doing something in a rush, it means if any part is compromised, it may have access to other parts. It can be okay to just have that one network, as long as you have subnets, security groups, and access control lists configured properly. If you don’t - it means if someone can exploit a library vulnerability in your web layer, they may have way too much access to any other servers, services running in the same network. And if someone can run exploit code in that machine, it would seem to be coming from within, from that network, so might have wider permissions than a call from outside. In some cases, the whole network may have exposed way too many vulnerable ports for the public internet to find.

This antipattern also includes wild manually created Bastion hosts. Bastion hosts are typically used as intermediate steps to access something within the network from the public internet. They can be carefully designed, deployed, and maintained, with good security controls implemented, or might be quick-and-dirty, abandoned-and-forgotten holes in your network.

So fix here is a bit similar than with buckets:

- Education: Know what you’re doing. If you feel even a bit unsure, start by watching a few good videos on the topics. Read AWS Well-Architected pdf. Know the concepts and principles.

- Main principle is to consider POLP and Blast radius, applying it to networks. Don’t expose more than you need to, try to treat every piece like it could explode. Consider what can be reached from that point, if it is compromised.

- Tools would be primarily security groups: You can define rules and access between them, without needing to declare specific IP ranges. For more exotic needs, access control lists may also possibly be used, for a bit more fine-grained control. Typically good to start with security groups, and see what you can do with them, first.

- Subnet design is also a good tool. We have the concept of public subnets, with a route to/from Internet, and private subnets, with no direct route to/from the public internet, only through public subnets, or public services. We also have tools like NAT Gateways, to support connection from inside out, but not from outside in, and of course, actual firewalls when needed.

- In more complex cases, might make sense to also define separate Virtual Private Clouds (VPC), which have defined interfaces between them, especially if some require direct connect or VPN connections to the on-prem network

So, if you love your services, and would like to keep them around, please consider the blast radius. Make sure you’re not vulnerable, paying special attention to any point that is connected to the public internet. This also includes publically available services that are not within any VPC. This would also be a great area to have some documentation, draw some pictures, so it can be discussed, audited, explained.

And by the way, if you define the networks as code (IaC), it’s easier and cheaper to reuse good patterns and avoid bad ones.

Antipattern #6: Multiple applications and teams sharing the same account

I’ve seen this antipattern a few times. Here are the symptoms:

- The same AWS account is used to serve multiple services. Which is not yet bad.

- But those services are built and maintained by multiple different teams, who all then have access to the same environment

- And previous problems with policy permission scopes, blast radiuses

- Also: the lifecycle phases of those services get confused. One team is running production workloads, another is doing a crazy POC and opening services and ports for the whole wide world, while still sharing the same VPC (in the worst case)

- Mixed responsibility: This is our team’s code, this isn’t, etc

- Mixed needs: One team needs public buckets and uses them for websites, the other team is supposed to have no open APIs or exposure to the outside world. The data they handle might have different sensitivity levels.

This is typically caused by some cost/time/bureaucracy/ownership related problems related to opening new AWS accounts. If it costs €300 a month per new account, or if it takes weeks to resolve a ticket, it’s not encouraging creating them, especially for small purposes. Also, when people ask who should receive bills, it might be realized that there is no owner to be found to pay them. These are excellent indicators that we’re trying to cram more waste inside a working environment. We are starting to organically grow a garden of evil.

While it IS possible to use things like taggings to separate resources, just be very disciplined and careful, and share the same account, the easiest path is to treat the AWS accounts as natural blast radiuses, and not put too much inside one. When there’s a good enough prospect for a service with some ROI, it should be possible to find the owner/sponsor (who is paying the bills) and create those accounts. Use accounts to separate lifecycle phases like dev, test, production, and any others you need. You can use AWS Organizations to group the accounts and have some governance over all of them.

For wilder experimentations or ad-hoc POCs, you can try to build a different capability: Either have a shared sandbox environment, in which anything goes, and it is nuked entirely regularly, to keep it clean and not hit any region limits. Or create a capability to create throwaway accounts easily, cheaply, rapidly, use them for a bit, then throw them away. Be mindful of not allowing anyone to run any production loads in a sandbox: Regular nuking, deleting anything in the account, helps with that too.

Antipattern #7: Billing creep

Here is the lifecycle of typical cloud migration. First people are protective of their beautiful handcrafted on-premises setups, where they have built a lot of controls and governance over the years. Then they hear the seductive whisper of a cloud platform, offering potentially limitless scalability and cost-effectiveness. Then they are a bit suspicious on how things could be migrated, or if new things are being built, how secure could that be, being in a public cloud. Then they find the courage or other incentives to make the first leap. And eventually, they fall in love. They realize that cloud services are typically much better maintained by much bigger workforces than any they have used before. Real cloud services typically don’t have any offline maintenance breaks, and while that scalability is not always limitless, or effortless, it’s still there and it’s incredible.

It’s possible to do AWS in a very restricted and controlled manner, by going through slow and expensive ticketing for each resource, but this is not the antipattern we’re talking about here. It would be worse than an antipattern because it would kill all the benefits mentioned here. But most companies use a model where the DevOps-teams have a lot of access within the account given to them, and traditional IT administration is only creating and monitoring the accounts. This model gives the benefits of speed and cost-effectiveness.

When a team starts building stuff within AWS, in an agile manner, they pretty soon discover that given enough power, they can create and scale resources pretty much immediately, even dynamically. This supports agile operations very well. Many of the resources are extremely cheap, and you get a lot of extra options that are ridiculously cheap to turn on and enjoy immediate benefits. Things like setting up the network to your needs, using encryption-at-rest or in-transit, getting storage without needing to worry about CPUs, licenses, or memory. Getting redundancy and disaster recovery by just clicking a few buttons. And it’s all very cheap, compared to setting up the servers to do all that yourself. And this is where the trouble starts.

You see, AWS has more than 175 products and services, and more are coming each year. Each has a different pricing model. Due to being able to immediately toggle on new services, which they have varying levels of experience, it’s relatively easy to turn on something that would cost a lot. Here are some examples:

- I’ve once seen a badly written SQL query that was being run in Athena every hour by a timed Lambda function. It was artfully missing all nicely generated indexes, and going through terabytes of data in the bucket, all of it. It was generating tens of thousands of euros of billing before it was discovered.

- Creating virtual servers, it’s possible to choose their type and capacity, and some of them can be very expensive if they are left running. Machine learning projects might often run these servers, but are typically not supposed to run them 24/7, only on demand.

- Sagemaker developer endpoints can also rack up some bill quite fast, it’s easy to create them and use them, but if you forget to shut them down, euros will start accumulating rapidly

- There are often few ways to model things, and the cost may vary quite a lot. Different patterns depending on your case.

- If you’re not seeing how much things cost, you might be enticed to create a new feature for the product, based on some new service just because you can. Perhaps it’s something you wouldn’t have even considered before.

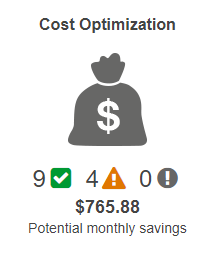

This can often be a problem because I’ve seen that billing is often abstracted, denied, and hidden from the development team. So the fix is rather simple: Create visibility for the costs. Use billing and costs as one input for your architecture, from the very beginning. This allows applying one AWS Architects centric skill: Cost optimization. This is again one of those things that can be expensive to fix afterward, it’s cheapest to build in cost optimization from the beginning. Having this visibility can help you make educated choices between different architectures. What you’re looking for is a steady growth of expenses as your resource usage grows, but any dramatic anomalies or changes in the bills should immediately be studied and understood.

Highly recommended also to enable billing alerts, so that you get a notification if you are going over budgeted amounts. Early warning, so you don’t need to study the reports every day. When you get a warning, you check if the change is valid, aka in line with improved architecture and increased value. Or if the change was unexpected, a result of a bad pattern or badly scaling architecture. Even experienced cloud developers have sometimes been surprised by the bills.

So: Keep that agility and velocity - but also keep your eyes open. Do also cost-driven development, in addition to all your other viewpoints. Don’t do things just because you can, think about costs, benefits, and ROI. That way you can make your development less eventful, but much more peaceful. Fewer surprises equal more happiness, in this case.

Conclusion

For each antipattern, there’s mitigation. If you build it in your development process, from the very beginning, life will be much better for you. Some of these are impossible to solve on very high and abstract levels, so are best-taken care of by empowered DevOps teams that want to carry the responsibility of not only building the services but making sure they run smoothly as well.

So remember a lot of acronyms and concepts: Do IaC and POLP, limit the Blast Radius.

I could have picked up a lot more of antipatterns but you gotta start from somewhere, and hopefully, these made you pause for a bit - or smile a happy smile because all this is already taken care of and you are an enlightened developer.

Also remember: You can fake it until you make it. In case you cannot automate everything immediately, including some of these in code reviews is already an improvement. Automation might bring more support for people who would like immediate feedback loops when they create an increment of value, in other words, might be something you want to invest in periodically more and more.