And now, something very different. This is not a story of a customer project. This is a tale of personal research that’s been cooking for some time now. To help you see why I’m talking about brains on a tech blog, I probably need to go back in history a bit first.

Why brains?

For me, two paths led me to be interested in brains. One is biohacking. I am a dabbler in biohacking because it makes much sense for my nerdy heart. Biohacking is about measuring, then making a theory, followed by a change, and then remeasuring. Much like a self-optimizing DevOps model. You change your lifestyle based on measurable feedback, you know, how science is supposed to work. Now, of course, you need to be able to measure. You can measure many things about yourself, even develop a bit of an addiction to it, for example, pulse, temperature, amount of sleep, exercise, so why not add EEG to that list as well, to monitor deeper your recovery or ability to concentrate?

Another thing is user interfaces. I also used to be a huge fan of science fiction and Cyberpunk roleplaying games. Wait - actually, I still am. For me, it’s always felt weird that tech professionals are still using an ancient user interface for interacting with the machines. The QWERTY layout for keyboards that we use today was created to slow your writing so letterheads would not get stuck in old typewriters. But it stuck. Keyboards are also quite large, require you to touch surfaces. On the other hand, they typically bind you to sit by your desk for that 8 hours stint and encourage you to not move too much. Mouses are all another story. Let’s just say, though they do have some good old-fashioned charm, and there’s recently a cult in building your lovely keyboards from scratch, I’ve always been interested in experimenting with alternatives. Not necessarily full replacements, but also supplemental user experiences. Especially in this year of the Great Pandemic, perhaps something with less touchy-feely?

So this has led me to also think about how we can interact with our environment, now and in the future. Touch UIs make much sense, and I don’t have to sell the idea of how useful they are anymore, since we have a new generation growing up who might have never encountered a keyboard and actually might live their life without owning one. Touch UIs are well established and great ways to interact with the environment. They have not replaced keyboards in all places, but in many places they have, and they have also found their way to many other places, where keyboards would not even be a good option. My 3-year old kid is constantly trying to swipe boring things out from the TV screen and is mildly frustrated when it does not work.

I’ve dabbled with gesture sensors, which enable you to have precise 3d control, and most importantly, not be touching anything. They also typically do not take so much space. Many touch interfaces are already being replaced by gestures. I’ll write another blog/do a video on those later on. That technology is so mature it’s not really hyped anymore, instead it’s ready to be used.

Voice control is also one favorite of mine, I’ve done a few apps with Alexa (I once wrote an office nagger in a hackathon, that you can set loose to remind people to log in their hours in a timely fashion so that you don’t need to :) - and control a lot of things in my house with voice. It’s not a keyboard replacement and has some security concerns as well, but becoming a father I often had my hands full, so it was blessed to be able to control lights and choose some relaxing music to play without needing to even use touch interfaces. Voice and speech is quite a natural way of interacting, and also very mature technology today, so it’s easy to create user interfaces with it. I’ve done my share of pizza orders via Alexa, for example (Until our 3-year old learned how to do that, too). We’ve had some queries already for creating voice interfaces in places where it’s not convenient to keep on washing/sterilizing hands to do a bit of a process on the computer, but of course in Finland, there’s not - yet - great support for natural language processing.

Then there’s Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality. A huge topic on their own. I have a dream that one day my workday would consist of me moving around grabbing constructs, attaching them, while using my voice to name things. I would get a full balanced workout during my day instead of needing to fix 8 hours of sitting afterward. VR and AR have immense potential, and start to be mature enough to use, but again, perhaps a story for another time.

So that brings us to brains. Being able to measure brainwave activity, makes it also tempting to use those measurements to control things. After all, it’s a very direct and fast line from thought to action, it’s also a very natural thing, since essentially we are already controlling everything with our brain. Also: No touch required, does not take space, does not limit you to sit at your desk. Unfortunately, maturity here is far from the other control devices listed here. Because potential is still there, a lot of people have been and still are doing research on this area, for example, Neuralink by Elon Musk, and now also Brains on Java by Yours Truly.

Brainwave theory 101

Okay, I did not major in brain sciences while I was doing my studies. I only got interested in that later. Additionally, my core interest is in software applications, so take this bit with a grain of salt. But I do need to give a brief introduction to how brainwaves work so that we can progress to what we can read from them. There may be horrible mistakes and misunderstandings - feel free to correct me in the comments if that’s the case, so we can get this right. There will be some over-simplifications to keep the length of this article down somewhat.

Brain activity is all about electric impulses triggering in our brains. As it’s electricity, we can measure it with suitable devices. Having a raw reading of that electricity of course only tells if there’s some level of activity or none. In other words, that’s not very useful, but it’s a starting point.

Things get more interesting when we take that signal, and split it into wavelengths, based on its amplitude.

Delta waves are the slowest bandwidth, from 0.1 to 3HZ, and indicate sleepest meditation or dreamless sleep, being unconscious. Remember, I’m not a brain scientist. Real brain scientists could tell you that there’s some variation on how these areas are defined, what are the limits, and how they are interpreted. But I’m not a brain scientist, so I simply equate slow brainwaves with a very passive and resting mind.

Next, we have Theta waves, about 4 to 7 HZ wavelength. Theta bandwidth typically activates when you are dreaming or daydreaming. It can be associated also with learning, intuition, and memory. Deep meditation, where your focus is drawn out from the external world, and concentrated deep within, would activate Theta bandwidth. Also, when you are doing a task that’s so automated you would not need to think about it at all, for example brushing your teeth, driving a car, or coding in Java.

Alpha bandwidth is the next area, roughly 8 to 12HZ wavelength. This bandwidth activates when you’re in a relaxed state, quietly flowing thoughts, not quite meditation, but not quite yet being active either. This could be associated with a short rest, self-reflection, your mind state just before going to sleep (on a good night). I would call this Void state, from martial arts vocabulary. Relaxed, calm, ready to move in any direction.

Then comes our next bandwidth, which would be called Beta, between 12 and 30HZ. This could be further split into lo/midrange/hi beta areas, which have a bit different nuances. But Beta bandwidth is overall associated with an activity, when your consciousness is directed towards problem-solving or when you are actively processing and learning some new information. I would argue that in our normal day of work Beta area would have a lot of movement. On high Beta-area, it can also be a tiresome state to maintain, which is why you need shorter and longer resting periods to balance things out.

The final bandwidth would be called Gamma, between 30 and 100HZ wavelength. This area was originally considered to be random noise until more recent studies defined it as an area that activates in some very specific states. When you are multi-tasking or experiencing feelings of universal love, altruism, or any of the higher virtues, you are probably activating Gamma. Gamma is above the frequency of neuronal firing, so how it is generated, is still a mystery. Gamma brainwaves have been observed to be much stronger and more regularly observed in very long-term meditators including Buddhist Monks.

So there you have it, my meager knowledge of brainwave theory. To do something with it, we need to be able to measure the different wavelengths, somehow. Then we need to be able to interpret some sense out of all that. Hmm, this is somehow familiar. A network-connected device that provides a constant stream of information. Isn’t that like.. a power generator? An elevator? A smart tv, a smart toaster, or a smart fridge?

Brains as an IoT device

I’ve been recently working a lot with IoT devices and cloud-native services. So this is a familiar place to be. You have a device producing some metrics or KPIs, then you record or stream those, and do some analysis, with or without machine learning. You probably want to store that data also somewhere, for later use or larger batches of analysis. So let’s go, what can we do with brains?

The first thing you need is a Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) of some kind, and an API/library to access it. I chose a commercially available Neurosky Mindwave headset, which is cheap, simple, and enough for my needs. It’s not going to stitch electrodes to a pig’s brain but gives me enough data to get started.

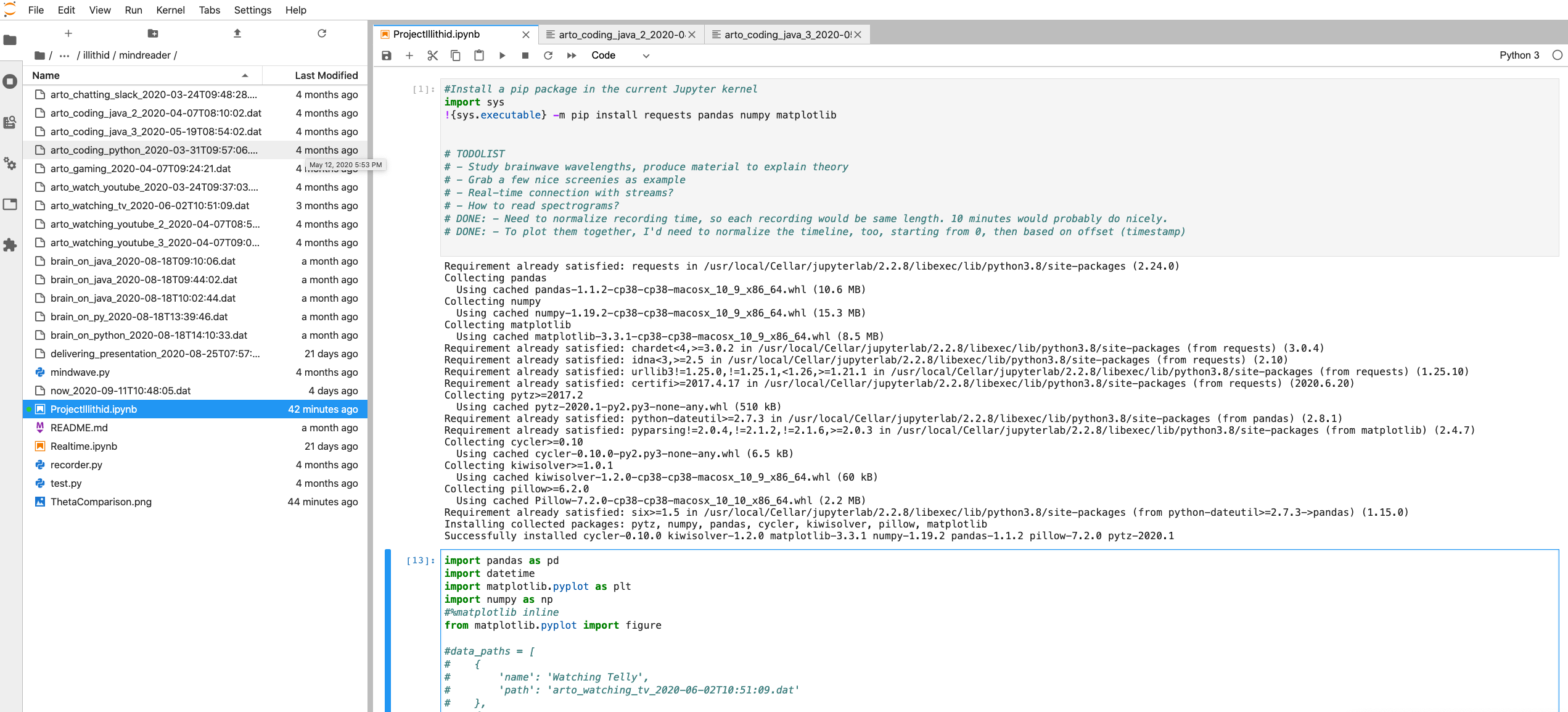

I created a git repository to store some tools and as of today, it’s publically available at https://github.com/crystoll/projectillithid

If you see something interesting, would like to experiment a bit too, go ahead, grab the code and build something fun on top of it. I decided to write the code in Python, after attempting some Java and Kotlin, due to ease of use for serial port interface across platforms.

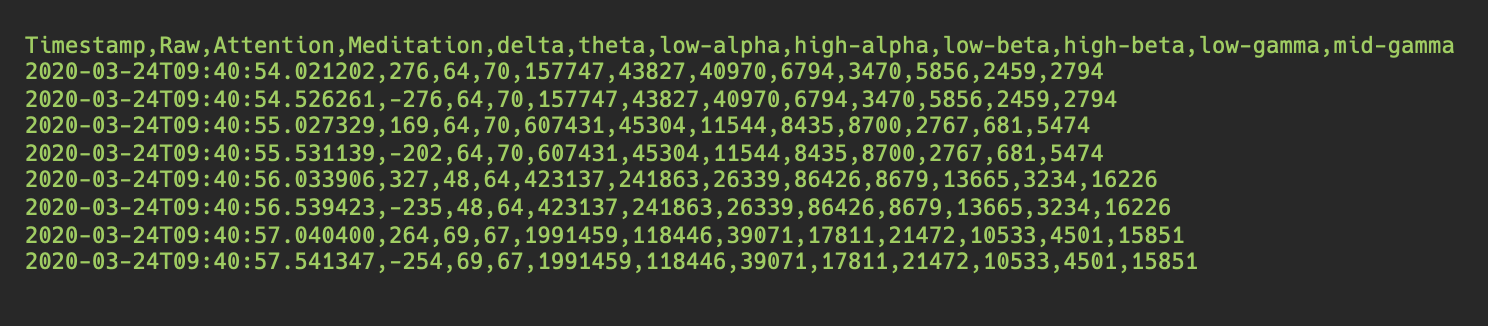

Unfortunately, many available libraries were written in Python 2, using more fragile mechanisms to connect, or just generally messy and unkempt, so I created my version. On top of that, I created a recorder program. What it will simply do: It will connect to the headset, and do a 10-minute recording of your brain activity, storing it to a .csv file for later processing. This recording will contain raw data, calculated bandwidth values, as well as calculated concentrated and meditation values. Once created, you can analyze it later with any tools you like. Here’s a snapshot of my brain:

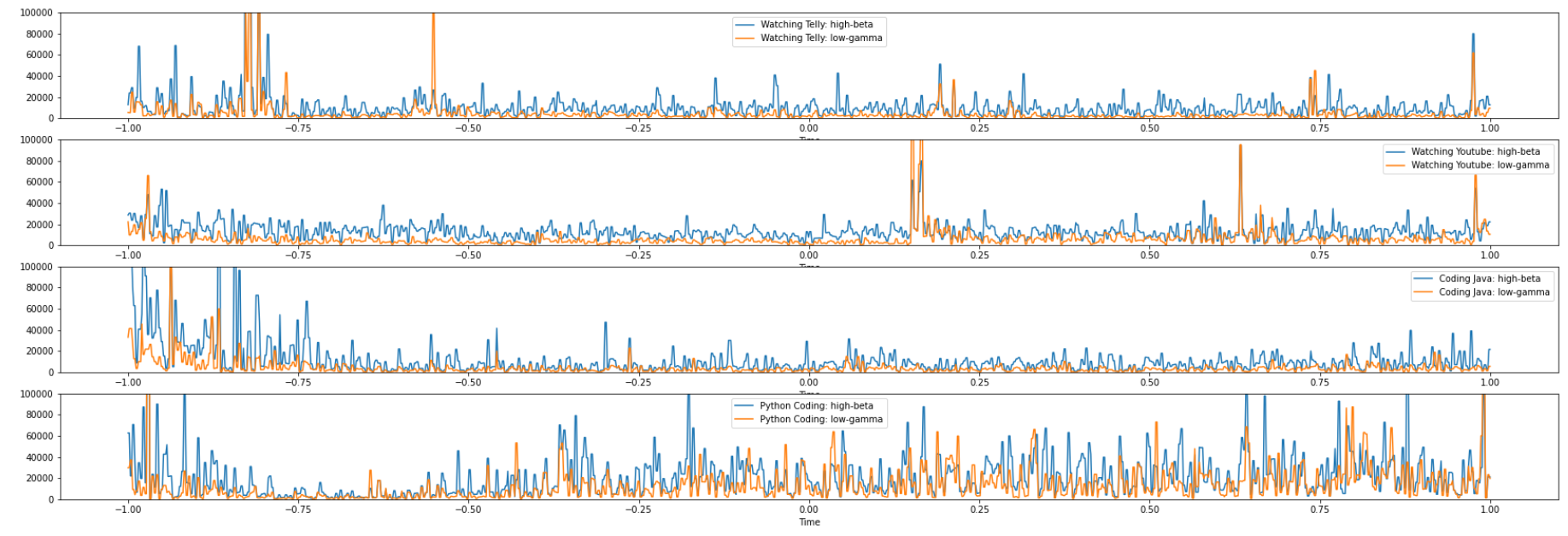

This was part of a recording I made while writing this blog. To make some sense of it, it helps to analyze it with some data-sciency tooling, so I wrote a template for Jupyter Notebook that can be used to quickly graph some interesting things about the data, in a much similar way to any other time-series data.

Finally, I also included a real-time Jypyter Notebook, that can be used to hook up into the brain directly, and plot any bandwidths realtime to a graph. That gives fun effects when you can immediately see how well you are concentrating/meditating for example. Talk about an immediate feedback loop!

Control the world with your brains

Being able to measure one’s brains while doing various activities can be fun from that biohacker/feedback loop perspective. Some athletic teams are using tools like this to improve their concentration or meditation skills or see effects of theoretical improvements. But you can go farther with this, too. After all, I started this story from user interfaces, so how does the brain work as a user interface?

Well, it turns out it’s not so good, really. You can detect the brainwave activity, and can deduce attention and meditation values, and eyeblinks pretty accurately. However you cannot detect more specific thoughts, so if you were planning to control a drone by giving it mental commands like ‘left’, ‘up’, etc, well, let’s just say you’d need to run some deep learning algorithms to be able to deduce that. Very deep ones.

Another problem is our wild untrained brain. If you figured out a control scheme where a binary input would be enough, for example, concentration/no concentration, problem is that brains are not cohesively maintaining that state. They will activate constantly multiple bandwidths at THE same time, and go from one state to another. That has not stopped some parties from experimenting with brainwave control, there are cases for example on how to control a wheelchair, or a mechanical hand - in this case, other persons mechanical hand. So I decided to give it a go, as well.

In the project repository, there’s a subfolder called ‘huecontrol’ - and that combines Mindwave headset library with a phue library for controlling Philips Hue lights. I hooked up a very simple algorithm that rewards being able to maintain a concentrated state - by turning up the light’s intensity. The intensity in this case means the brightness of the light, and for colored lights, it also changes hue to more and more red. So you concentrate - and lights will turn bright and red.

This blog post is obviously not the place for a live demonstration, but I did this presentation on our internal developer days event, and there’s a Youtube recording already out on how it looks like. Pretty simple actually, and I would say 95% useless, but fun!

Conclusion: Did I learn anything useful?

Well, using EEG to control things around me is pretty limited and difficult. Although I do believe with feedback loop one can train their mind to better be able to concentrate. I’ve seen people do that, and they can easily go to a concentrated state, and maintain it for minutes without wavering. The technologies are also improving every year, new research being made, so if headsets improve, and we use machine learning algorithms to interpret the results, I believe things can improve. As I mentioned, the brain-computer interface is the most intuitive user experience possible: It removes all intermediaries. You think it, you do it. So quite fascinating to follow up on this.

As for recording and analyzing your brain, that’s a much more mature part. Tools are available, and with the fast feedback loops, you can improve whether you need to concentrate or relax better. I am already using Oura rings to measure my night’s sleep, so combining daily brainwave data with that seems natural and interesting.

And of course, if I think about the brain as an IoT device, any tools or methodologies that deal with that kind of data are practical for me. I did one experiment, which is not in the repository, but a little bit of Kotlin connected my headset feed to AWS Kinesis stream. Then I can apply some Kinesis Analytics to refine the information further, real-time. Now the fun thing about streams like that in the cloud is that they scale pretty well. So if I had more headsets, I could hook up more live feeds and interpret them simultaneously. For example, knowing which bandwidths activate on creative thinking, or practical problem-solving, or concentration, it would be possible to give some good feedback loops not just for individuals, but for the groups. Might be a fun exercise at least.

And of course, collecting recordings from multiple people doing multiple activities, perhaps today’s scalable machine learning approaches could dig a bit deeper, to find commonalities. I would actually bet that there are those to be found since different activities seem to activate multiple wavelengths in predictable patterns. So could we teach the AI to recognize words like ‘dog’… I don’t know. You tell me. If you got hooked, grab yourself a BMI, grab that code from Github, and start building!

Here are some resources if you want to dig deeper: