Modern frontends are complicated things. Most modern web applications use some form of the single page application (SPA) approach, like React or Vue, to deliver the user interface. This approach makes sense in many cases as it separates the frontend and the backend work cleanly.

The SPA approach also bundles JavaScript (or anything that compiles to it) and related assets into something the browser can consume. The role of the backend becomes to serve the initial page that contains the frontend app bundle and then serve its needs via an API (like REST or GraphQL).

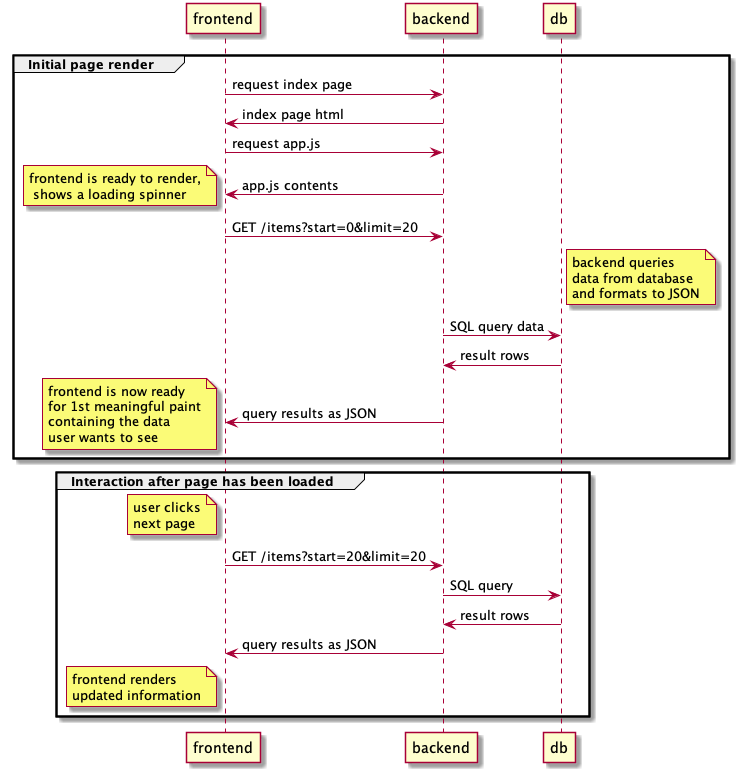

The image above shows a simplified startup sequence for a hypothetical SPA frontend that shows some data queried from a database. There’s quite a lot that needs to be done before the frontend is ready to render the data the user actually wants to see. The subsequent interaction after the initial page had been loaded is much less work.

A new (old) approach

The SPA approach is good for many applications, but it does add a lot of complexity. In the halcyon days of the early 2000s the go-to way for web development was fully server side rendered, like JSP or PHP. There was no API, the server simply rendered full pages and used whatever database resources it needed to fill in the dynamic parts. JavaScript was mostly used for simple enhancements like form validation before sending.

There’s nothing wrong with making a fully server-rendered application today, but many applications have needs and user expectations that require more fine-grained updates than reloading the page with each user interaction or refreshing the page to check for new updates.

We can combine the server-side rendering with WebSockets to provide granular updates to the browser and receive callbacks. We can have our cake and eat it too!

Ripley to the rescue

Ripley is a new Clojure library that implements a fully server-side-rendered programming model that can serve full pages but also takes care of updating things that change without page reloads. You can create rich webapps without the need for an SPA frontend.

Creating user interfaces with Ripley should feel similar to browser side frontend development: you create functions that take in data and render HTML output.

;; create a shared state counter (shared by all users)

(def counter (atom 0))

;; function that takes in counter atom and renders the UI

(defn counter-app [counter]

(h/html

[:div

"Counter value: " [::h/live {:source counter

:component #(h/out! (str %))}]

[:button {:on-click #(swap! counter inc)} "increment"]

[:button {:on-click #(swap! counter dec)} "decrement"]]))

The above example looks similar to Reagent

(a ClojureScript React wrapper), but it is all rendered on the server.

The button callbacks defined with :on-click are actually run on the server.

The special [::h/live ...] element registers a source on the server for this

page. Whenever the atom changes, Ripley re-renders the component on the server and sends

the resulting HTML via WebSocket to the client.

Ripley includes a tiny JS client library that does the WebSocket handling: sending event handler callbacks to the server and patching in new fragments received from the server.

Ripley tries to be as efficient as possible and the HTML output is optimized at compile time by prerendering all static parts to HTML that can be directly written to the result stream.

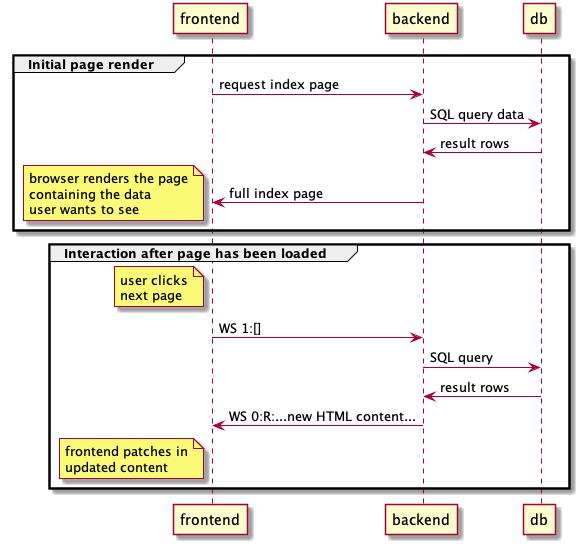

The image above shows the same hypothetical application with Ripley. The client requests the page and directly receives HTML having all the content in place. The subsequent interaction is interesting as well. When user clicks the “next page” button, only the callback id and possible arguments are sent to the server via the WebSocket. The server will run the query and send only the changed part of the page back over the WebSocket.

The basic model is that a live component is rerendered on the server and its full HTML is sent back but Ripley can also delete elements, append or prepend content or change attributes. The update granularity can be decided per component when implementing live components.

The model has many implications and some trade-offs we will explore next.

Time to interactive

SPA frontend apps are often large applications that the client needs to download before it can render the page for the user to see and interact with. This problem has some workarounds like module splitting and server side rendering with hydration. These solutions bring extra complexity that your application and build process needs to deal with.

With Ripley we just send the HTML of the page ready to go. The usual markup for a page in the application is likely tiny compared to the frontend JS code and API payloads.

No need for an API

With an SPA frontend you still need a backend to service the data needs. Most applications will need to fetch things from a database and store new things to the database. This essentially turns the backend into a database API. That’s fine if you need it for other clients as well, but it shouldn’t be necessary just to service your frontend.

The API will also need to encode information to some format (often JSON) and your frontend will need to parse the information. With server side rendering this extra round trip can be completely avoided.

No need for client side state management

With the backend being a database API comes another important source of complexity: client side state management. You need a way to store the information on the client and make sure that long lived pages aren’t stale. Programming a two way synchronization of frontend app state and the backend database is interesting work to be sure, but the complexity is incidental and has nothing to do with the particulars of your application. If you can skip it, that’s more code that doesn’t need to be written and debugged.

Leveraging browser strengths

Single page application frontends often require special handling to mimic a browser’s native navigation with pushState. Refreshing in an SPA frontend means losing all the accumulated state and having to refetch everything. That’s mitigated with frontend routing libraries, but those too are another source of incidental complexity.

The browser is very capable of caching your static assets so page reloads are not a big problem for most resources. Make sure you help the browser do its job by providing proper caching headers.

Build complexity

Traditional server side rendering can be done with a single server project. A separate frontend and backend requires two builds each with their own dependencies and build steps. Now many would say separation of concerns and differing skill sets needed for frontend and backend work makes this split beneficial. That split then requires synchronization between the projects or some flexible API like GraphQL.

In my experience full stack development is very common and the same people are doing everything from frontend to backend so the separation argument isn’t very convincing to me in many cases.

Server resources

With WebSocket-enhanced server-side, Ripley effectively treats the browser as a dumb display client. The app logic for the dynamic parts have to exist somewhere. This requires server resources for each user that has the page open. This may or may not be a problem depending on the case. A single server can easily handle thousands of connections.

The requirement for constant network connections makes this approach unsuitable for use in serverless cloud platforms.

Interaction latency

Some applications require very rich interactions and those will benefit most from executing logic directly on the browser. But given that the average human reaction time is over 200 milliseconds there’s plenty of time for a server round trip in most cases. Perhaps a rich text editor component will need browser side components still but common CRUD applications with tabular listings and forms are no problem.

Closing remarks

While Ripley is still a very young library, the techologies used are nothing novel. Server side rendering has been with us since the beginning of the web and WebSocket support in browsers has been around for nearly a decade.

Ripley isn’t unique in providing this sort of programming model. It was heavily inspired by Phoenix LiveView.

I believe that server side rendering with live enhancements will be a good fit for many applications and we will see increasing adoption of these strategies. That said React and other client side UI frameworks will still likely rule the modern frontend landscape especially with serverless computing being on the rise.