I must confess: I have absolutely no knowledge on machine learning. Of course I know the basic idea and the concepts. If someone would have asked me to build a program that can detect if an image is a hot dog before the experiment described in this blog post, I wouldn’t have had any idea where to start. So machine learning was definitely something I wanted to dig into during my summer vacation. To be exact, I dug into deep learning, which refers to machine learning utilising neural networks. Don’t worry, I did not spent my whole vacation on my laptop, and this experiment was actually pretty fast to carry out. I would say this took me about 15 hours or so.

Autonomous cars, which run purely on visual and other sensory input, are fascinating. Hence I initially wanted to build a simple car or a robot which would run on track autonomously. I also encountered a thing called Donkey Car, which is sort of an open source alternative for AWS Deep Racer.

But the physical world poses problems:

- I don’t have a lots of knowledge about electronics

- I’m not a particularly crafty person

- Gathering the components would take money, and more importantly time, and I wanted to get started quickly

- I would need a track which would take at least a good half of our living room and my partner might have an opinion on that

Then I remembered a really entertaining and fascinating video series by sentdex called Python Plays: Grand Theft Auto V. If you haven’t watched that, you definitely should take couple of hours and watch - it’s super educational and fun.

And BANG it hit me while sipping a cup of joe on my backyard: I’ll create a really simple game in which the player “drives” and tries to avoid obstacles and then try to use the techniques described in the autonomous GTA video series to teach my laptop to play my game. So it’s a simulation of my future endeavours!

You might ask why I didn’t just pick a simple game from the internet? It’s because I wanted to keep the machine learning part as simple as possible, and thought that the easiest way to achieve this is to have full control of the game mechanics.

The Game - Endless Flighter

I poured another cup of joe, and rolled up some Parcel and Three.js. After couple of hours I had Endless Flighter all set up and running on my browser.

Almost as simple as possible game in which you can steer left or right and you should avoid obstacles. I did not even implement collision detection, because I realized that it is not actually needed and it would only make things more complex. This way my learning data collection and testing the model is much more straightforward.

The AI Infrastructure

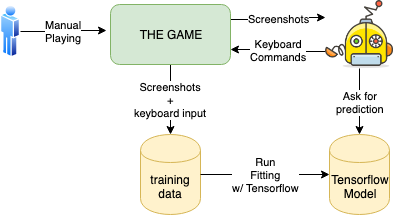

The rough idea I learned from those Python Plays GTA videos is this:

- Implement a capturing mechanism that takes screenshots, preprocesses them and registers pressed keys at the time of the screenshot

- Capture lots of data by flying manually

- Balance the data

- Pour data into TensorFlow which creates a model from your data (this is the ???? part for me)

- Implement another program that captures the screen, preprocesses the image with the same exact mechanism as in capturing stage, and then ask neural network (the model) for the prediction for the image. Then press buttons as predicted 👌

- You have an autonomous agent 🤖

I shamelessly copied most of the code by sentdex almost directly and just tweaked things to fit my needs and ideas.

All the code used in my experiment is available here.

1. Capturing the data

So the first thing to do is to implement a program, which captures whole lotta screenshots of manual flying and tracks keypresses.

This is actually pretty easy to do. Just place your game on a certain position on your screen and use ImageGrab or a similar program to grab that image.

Then you probably need to convert the image to grayscale because colour images are huge compared to grayscale images. If you have more complex game, you probably should also apply edge detection and other image processing techniques to the images in order to render them more simple for the neural network. Grayscaling seemed to be enough for my simple game. It’s also important to make learning data as small as possible, so don’t use 600x600 images but instead scale images down to 60x60 or so - it should be enough for the neural network to figure things out.

To get the current state of the keyboard, I used pynput and came up with a script containing ugly global state :p

from pynput import keyboard

a_pressed = 0

s_pressed = 0

def on_press(key):

global a_pressed, s_pressed

if(key.char == 'a'):

a_pressed = 1

if(key.char == 's'):

s_pressed = 1

def on_release(key):

global a_pressed, s_pressed

if(key.char == 'a'):

a_pressed = 0

if(key.char == 's'):

s_pressed = 0

def kb_state():

return [a_pressed, s_pressed]

listener = keyboard.Listener(

on_press=on_press,

on_release=on_release)

listener.start()

Then I used this beast to capture the data and to store it in a numpy file

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import numpy as np

from PIL import ImageGrab

import cv2

import time

import keypress

import os

file_name = 'training_data.npy'

if(os.path.isfile(file_name)):

print('File exists')

training_data = list(np.load(file_name, allow_pickle=True))

else:

print('File does not exists')

training_data = []

while(True):

screen = np.array(ImageGrab.grab(bbox=(20,220, 420, 450)))

screen = cv2.resize(cv2.cvtColor(screen, cv2.COLOR_RGBA2GRAY), (80, 60))

keys = keypress.kb_state()

training_data.append([screen, keys])

if len(training_data) % 100 == 0:

print(len(training_data))

np.save(file_name, training_data)

What it does is:

- Take a screenshot

- Convert to grayscale

- Resize to 80x60

- Get the current keyboard state

- Store image and the corresponding keyboard state in an array of tuples

The data is structured as:

[

[image_matrix, keyboard],

[image_matrix, keyboard],

...

[image_matrix, keyboard]

]

Above is a visualisation of the learning data replayed. On the terminal, you can see which buttons were pressed, and on the window is the corresponding screen.

I got a pretty low frame rate of a couple of images per second, but it turned out that this frame rate is actually enough for my simple Endless Flighter game. Note that the images in the learning data are cropped so that the bars behind the player are not visible. This originates from my assumption, that the bars already passed do not matter anymore. When you play the game, you focus your vision to the upper part of the screen.

2. Capture Lots of Data by Flying Manually

I wanted to make this work end-to-end with a minimal training data set, because I did not want to spent hours flying the most dull game in the history for hours and then see that it didn’t work and the data is corrupt somehow. So I decided just to fly for a couple of minutes and try to achieve an end-to-end solution which will probably be really bad because of the small amount of data.

3. Balance the Data

I learned, that overfitting is a common problem with neural networks. Overfitting means that you have a too high proportion of certain values in the learning data and then the network would pretty much always output these saturated values. In this example, flying straight is way more common than steering, so overfitted network would always fly straight. To overcome this, you’ll have to drop additional “flying straight” examples to match the steering examples. The goal is to get roughly the same amount of targets (keyboard states) to learning data.

One of the most interesting things is that the ordering of the examples does not matter. Most people would intuitively think that playing this sort of game is contextual, meaning that the previous examples (what happened couple of seconds ago) affect the current status. But this is not how neural networks work, as neural network do not “see” the previous images. Learning data is shuffled, and replaying the balanced learning data visually does not make any sense for human anymore - it’s just a collection of images and corresponding keyboard states in random order.

I also made a small mistake in the learning data capturing stage, because I captured keyboard presses in a form of an array of [a_pressed, s_pressed]:

[0, 0] # nothing pressed

[1, 0] # a pressed

[0, 1] # s pressed

TensorFlow produces predictions for the probability of the output for input, so you would get back an array of two elements. So for a screenshot, you would get back something like [0.493, 0.984] which would suggest to press the s button, because the second value in the prediction array - which denominates the probability for s key pressed - is larger. Usually you would select the action with highest probability and this would mean that our self playing agent would always turn to some direction, because there is no probability for going straight. To overcome this, I just simply mapped the data as following:

[0, 0] -> [0, 0, 1] # Go straight

[1, 0] -> [1, 0, 0] # Steer left

[0, 1] -> [0, 1, 0] # Steer right

From this data, I get predictions in a form of [go_left_prob, go_right_prob, go_forward_prob].

4. Enter the TensorFlow

This is the part of my experiment that I had absolutely no knowledge of. I just simply copied the neural network used in GTA examples and I learned only one thing: the input and output have shapes which must be defined in the network.

This is the neural network configuration used, but I have absolutely no idea what it actually does. 😂

# alexnet.py

# Shamesly copied from Python plays GTA videoseries

# https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLQVvvaa0QuDeETZEOy4VdocT7TOjfSA8a

""" AlexNet.

References:

- Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever & Geoffrey E. Hinton. ImageNet

Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. NIPS, 2012.

Links:

- [AlexNet Paper](http://papers.nips.cc/paper/4824-imagenet-classification-with-deep-convolutional-neural-networks.pdf)

"""

import tflearn

from tflearn.layers.conv import conv_2d, max_pool_2d

from tflearn.layers.core import input_data, dropout, fully_connected

from tflearn.layers.estimator import regression

from tflearn.layers.normalization import local_response_normalization

def alexnet(width, height, lr):

network = input_data(shape=[None, width, height, 1], name='input')

network = conv_2d(network, 96, 11, strides=4, activation='relu')

network = max_pool_2d(network, 3, strides=2)

network = local_response_normalization(network)

network = conv_2d(network, 256, 5, activation='relu')

network = max_pool_2d(network, 3, strides=2)

network = local_response_normalization(network)

network = conv_2d(network, 384, 3, activation='relu')

network = conv_2d(network, 384, 3, activation='relu')

network = conv_2d(network, 256, 3, activation='relu')

network = max_pool_2d(network, 3, strides=2)

network = local_response_normalization(network)

network = fully_connected(network, 4096, activation='tanh')

network = dropout(network, 0.5)

network = fully_connected(network, 4096, activation='tanh')

network = dropout(network, 0.5)

network = fully_connected(network, 3, activation='softmax')

network = regression(network, optimizer='momentum',

loss='categorical_crossentropy',

learning_rate=lr, name='targets')

model = tflearn.DNN(network, checkpoint_path='model_alexnet',

max_checkpoints=1, tensorboard_verbose=2, tensorboard_dir='log')

return model

Then I just ran some code that fits the data to the neural network and to my surprise, it worked and TensorFlow produced the model files!

5. Implement the Agent

Implementing the agent is pretty similar to implementing the capturing mechanism, but instead of capturing the current keyboard state, you ask for a prediction for the image from the neural network and use the given result to send a keyboard event.

import numpy as np

from PIL import ImageGrab

import cv2

import time

from pynput import keyboard

import keypress

import os

from alexnet import alexnet

from pynput.keyboard import Key, Controller

keyboard = Controller()

WIDTH=80

HEIGHT=60

LR = 1e-3

EPOCHS = 8

MODEL_NAME = 'endless-flighter-{}-{}-{}.model'.format(LR, 'alexnetv2', EPOCHS)

model = alexnet(WIDTH, HEIGHT, LR)

model.load(MODEL_NAME)

while(True):

screen = np.array(ImageGrab.grab(bbox=(20,220, 420, 450)))

screen = cv2.resize(cv2.cvtColor(screen, cv2.COLOR_RGBA2GRAY), (80, 60))

prediction = model.predict([screen.reshape(WIDTH, HEIGHT, 1)])[0]

moves = list(np.around(prediction))

print(moves, prediction) # Just to see things

if moves == [1.0, 0, 0]:

keyboard.press('a')

keyboard.release('s')

elif moves == [0, 1.0, 0]:

keyboard.press('s')

keyboard.release('a')

elif moves == [0, 0, 1.0]:

keyboard.release('a')

keyboard.release('s')

6. Let the Agent Play

Then I set things up, fired up the processes and to my sheer amazement, the player moved to some directions on the first try! It made mistakes and wasn’t particularly intelligent but at least it did something. I guess this was the first (and probably the last) time in my life when something like this seemed to work at least to some extent on the first try.

Then I played my game for about 20 minutes and captured all the data. After balancing the data and fitting the model I got something like this:

And I was like:

Mission accomplished!

It still makes mistakes, but at least it’s clearly trying to avoid the obstacles.

Then I spent the most dull 40 minutes, and the model got better. It still gets distracted once in a while, but is clearly better with more data.

I wouldn’t jump into a self driving car which is using my neural network, but I think I got pretty darn good results for the first try. I guess the main factors to my successful experiment were:

- The game is really simple

- Visual outlook of the game is really “predictive”

- It’s easy to collect steady and unskewed learning data

Onward to the World of Machine Learning

Isn’t all machine learning done with huge data sets, using massive GPU arrays from the cloud? Probably true, but you can easily start learning this stuff with just your laptop and CPU and you don’t need a GPU to get started. My largest 40 minutes learning data was just about 40MB in size and I got pretty decent results. The training with TensorFlow took about 5 minutes or so. So go on and try something out! For me, this was probably the most fun project I have ever done.

It’s almost a magical experience when you see your agent playing the game for the first time when you can see something clearly “intelligent” and you haven’t programmed a single line of logic yourself, but instead passed loads of data somewhere to make predictions from.

I’m pretty sure, that I am now able to create a program that tries to detect, if an image contains a hot dog.

We’re not in Kansas anymore.