The usual story with the test data

It’s not enough to test a system with one or two manually generated data points if the real usage will be in order of millions rows in the database. At the same time, it’s usually not feasible to maintain a full copy of the production database for all daily development and test needs. Many developers have created various “test data generator” suites that can generate a bunch of entries to the system, but the data is made to look like it came from actual usage and doesn’t contain malicious and weird inputs.

What if you don’t have the generator and don’t want to bother writing one just now?

The “nice” generator can also give a false sense of security. How do you know everything works correctly with weird inputs if you never test it?

Enter Burp Suite

Burp Suite is the de facto tool for professional security testers and security researchers to attack web applications. It contains a lot of functionality and is constantly expanding. I will only touch some functionality in this article, relevant to purposes of generating test data.

OWASP ZAP is a nice free open source tool, which could be used in a similar fashion.

First, let’s create one entry manually

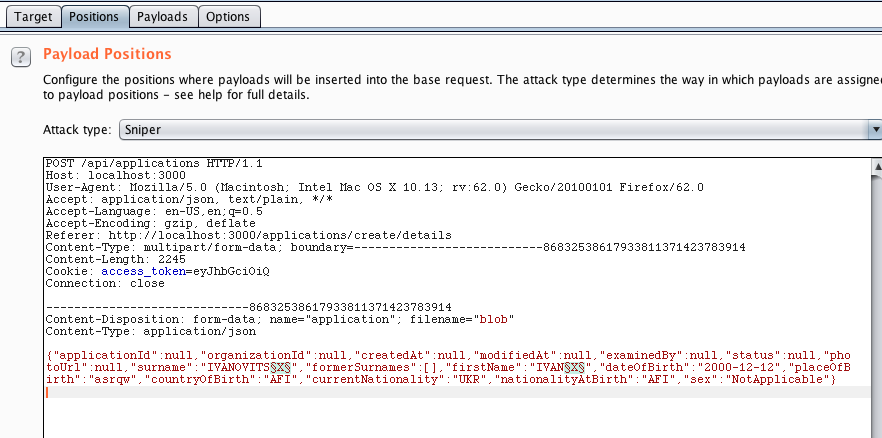

I created a single entry manually from the browser and Burp captured the traffic. After that the request can be sent for further processing to one of the Burp’s “tools”, like Repeater, Attacker or Intruder. Repeater is rather boring as we would need to edit the request manually so we’ll skip that here.

Intruder attack!

From the proxy view it’s simple to send the request to Burp’s Intruder which is a tool to create multiple attacks against the same endpoint and customize the attack. The user can select which parameters or HTTP headers to test and what kind of encoders and value generators are used.

First we need to select which part of the request we want to attack. In this case I have marked the name fields as the targets.

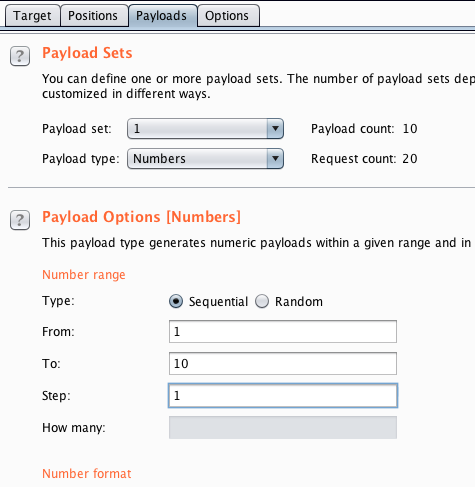

Next, I can select the value generator. In this case, for simplicity, I have chosen to generate numbers 1..10 but there are many other possibilities. You could even attach Radamsa to fuzz inputs.

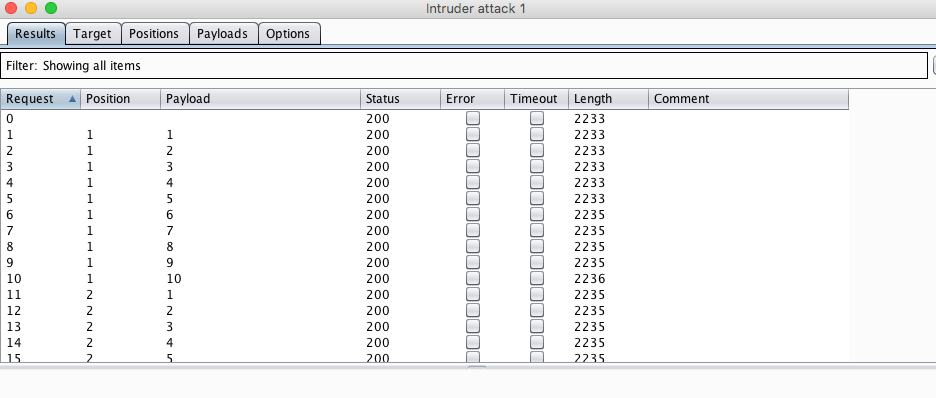

Finally, let’s attack and in a matter of seconds we have a lot of data in our database.

If you want to generate test data that is painful to handle, you can use nice input lists through the Intruder, like this Big List of Naughty Strings. Something from SecLists may also reveal what the developer missed in input validation.

Does this make any sense?

This is far from perfect in the sense that the data is not realistic. This can’t compete with a custom made test data generator, but it’s a significantly bigger effort to write that test generator. And if you want to create actually malicious inputs, how do you do that with your custom tool? Download SecLists and bolt them in? Maybe, but that’s even more work when you could just take Burp and press a few buttons.

Naturally you can automate all of this. Then you don’t even need to press buttons, just run it in the CI pipeline.

Enough talk. Attack!

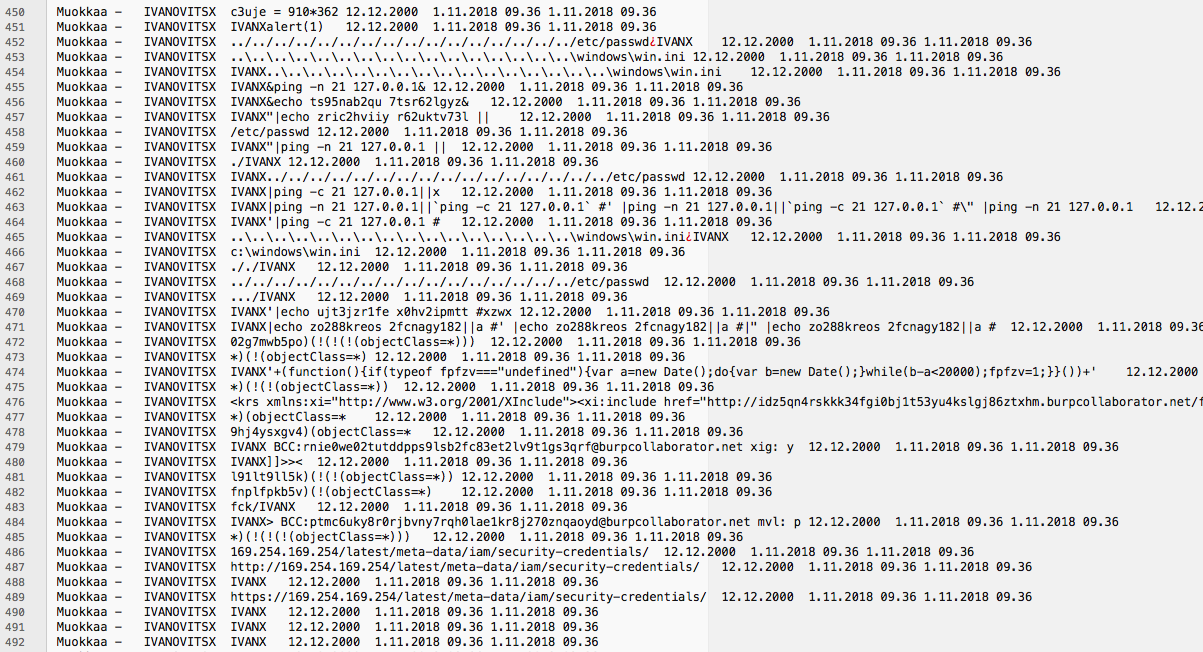

Burp has another nice tool that can generate requests, the Attacker. It’s basically a web app scanner, similar to Nessus, Acunetix, ZAP and the like. It tries to enter various malicious inputs to the fields in the request and based on the server’s responses it might find some actual security flaws. But assuming the backend server is not actually vulnerable and doesn’t crash when faced with such hostile requests, this can be used to generate some rather interesting data entries in the database.

So, I chose only the endpoint that creates data as the target, and launched an attack. Behold, what a jolly bunch of awesome people I now have in my local database!

I can pretty much guarantee that your puny test data generator won’t generate a person with a handy name like this:

IVAN IVANOVITSX|ping -n 21 127.0.0.1||`ping -c 21 127.0.0.1` #' |ping -n 21 127.0.0.1||`ping -c 21 127.0.0.1` #\" |ping -n 21 127.0.0.1

Using the attacker generated input

If there is a second order problem with the system, the scanner may not be able to detect it. For example, a stored XSS where the XSS is triggered in some other page not directly related to the store endpoint, might go unnoticed. Same thing for second order SQL injections. But if a human browses the application after the attack has run it’s course, such issues can be very visible.

You could also see all kinds of encoding issues and trouble with assumptions about field lengths and so on, which may not be security flaws, but you would want to fix them anyway because they are bugs in the system. This is something security testers rarely think about because they are not rewarded if they report mundane ordinary bugs to the developers. As a developer or QA engineer I would like to know about all bugs, not just the ones that could be exploited at the moment.

Why should we care about messieur IVAN <scRIpT>alert(42)// ?

Because he’s awesome and he has now mastered omnipresence. He’s everywhere. The notorious IVAN <scRIpT>alert(42)// will come to visit you one day so better prepare for that. Make sure your system doesn’t crash or worse. Even if no one tries to hack you, sooner or later someone will throw something extremely weird into your API. Don’t think you are fine because you are using some hocus pocus encoder library or parser. You either test it or someone else will - without your permission!

The good news is that this is a low hanging fruit. You don’t need to be a hard core hacker to do what I described here. Any developer could do this with a few hours of practice with the tools. It’s much easier to detect the easy bugs and potential security flaws than to actually exploit them succesfully, but a huge amount of security issues really boil down to input validation.