You cannot always choose where your application will be hosted. Sometimes the network infrastructure can be unreliable, meaning that network requests can at times take a long time to complete and requests will fail at random rates. Even if these problems could not be prevented from happening, luckily we, as application developers, have some tricks we can use to make our applications feel more stable in unreliable network. And even if your network infrastucture is solid, it is not guaranteed that occasional communication failures will not happen, as illustrated in Two Generals Problem. Thus, these quick tips, targeted mainly at single page web application and mobile application developers, will probably help your application appear more stable and responsive for your end users.

Avoid Making Network Requests as Much as You Can

The best way to avoid getting failing network requests is of course to avoid making them completely.

Even though this is very efficient, it is not very practical for most of us. The majority of web and mobile apps depend on getting data from servers, and thus, making network requests is mandatory. Still, even if we cannot avoid them completely, it is possible to reduce the number of or otherwise optimise the requests in order to achieve a suitable compromise.

Optimising Network Requests

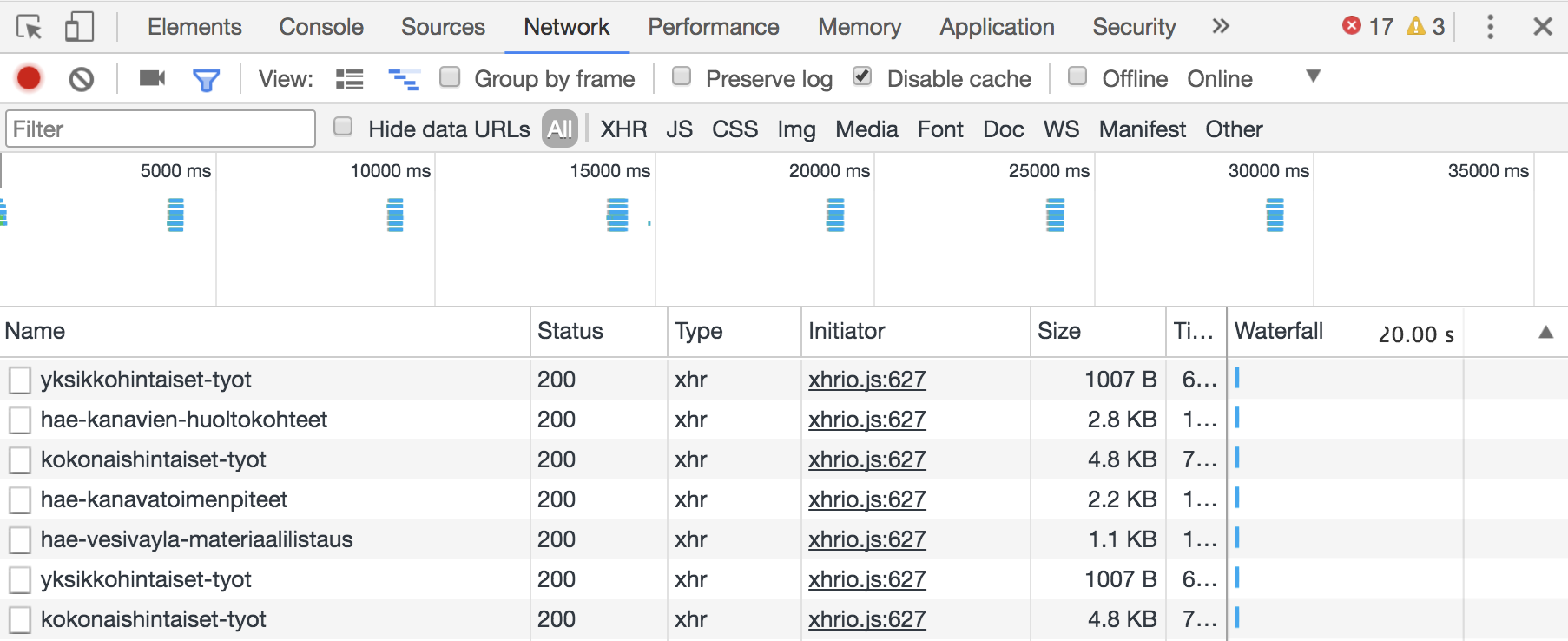

How can we optimise network requests? First, we should analyse what kind of requests our application is making. The developer tools of Chrome and Firefox are very practical for this analysis. On the network tab, you can see all the requests your application is making.

The way to optimise network requests depends on your application. The following questions can help you to find the requests that could be improved:

Are you making two separate network requests for saving data and then getting the same data again from the server in order to update the view?

The principle of responsibility segregation is a good thing in API design. However, using separate requests for saving and updating the view can be slow and error-prone if one is successful and the other is not. In this case, you might consider changing the implementation of the data saving API to return the updated data. This way, you can save the data and update the view with one request.

Another possible improvement would be to use optimistic update: we assume that most of our network requests are going to be successful. After sending the network request we update the app to the state in which it has supposedly completed successfully, without really waiting the actual request to complete. Only in the case of failure, we revert the view back to match the server’s response. This will make the application feel more responsive to the end user, especially in cases when data is edited visually. A possible downside is that the user is not sure whether the data was actually saved or not, so perhaps the user should be informed when the data save operation has been verified to have completed.

Are you making multiple network requests to get data for a specific view?

Consider combining these requests, i.e. making a single API method to return all the data for a specific view. This way you get all the data in one query. The downside is of course that you need to wait for that one query to be complete for the view to be ready, and if that one query fails, you do not get any data at all. GraphQL is a good example of a query language which allows clients to define the exact query parameters and the structure of the data returned from the servers.

Is some specific request slowing down the initial render of your application?

Your users want your application to load as quickly as possible, and thus you should only make the network requests that are absolutely mandatory to get your application up and running. If the network infrastructure is unstable, getting the application to load itself can take a long time or even fail completely.

Retry with Increasing Timeout

Now that we have optimised the network requests, it is time to make sure those requests pass to the server and back as often as possible. Application level network requests always operate on top of lower-level transmission protocols, such as TCP. These protocols try to provide an abstraction of a reliable connection. This is achieved by the sender detecting lost data and retransmitting it to the receiver automatically. So, if lower-level protocols already try to abstract a reliable connection in every situation, why would we want to write our own retry mechanism on the application level?

The answer is that application level network requests, such as HTTP requests, can appear to finish, but still transiently get an error code from the other end. This can happen if there are some transient errors in proxies or load balancers. If we cannot fix these problems by making modifications to the network infrastructure, we can abstract a more reliable connection on the application level.

Rather than calling the application environment’s native functions for sending network requests every single time we make a request to the server, one could consider writing a separate communication API for your application. The idea of this API is to be a wrapper for the environment’s native network request functions. The difference is that, with our own API, we can make global modifications on how the requests and responses are handled. For example, we can automatically retry failing requests.

The idea with retrying requests is the following: when our communication API is called to send a request to the server, it does this normally and returns the successful response to the caller. However, if the request fails, our API waits a few seconds, and tries to send the request again. If it fails again, it waits longer, and tries again. If the request fails too many times, the API returns the failed request to the caller. In most cases, hopefully, the request is going to be successful after one or two attempts. The caller of the API does not know of the failed requests. It does not need to, as our API automatically keeps (re)sending the requests. The caller is informed about the failed request only if it has failed multiple times. Here is a naive example of a communication API written in ClojureScript:

(def default-retry-options {:timeout nil

:attempts 5})

(defn network-request

([response-chan request-options]

;; network-request called without retry-options, use the default value.

(network-request response-chan request-options default-retry-options))

([response-chan request-options retry-options]

(let [response-handler (fn [[_ response]]

(if (= (:status response) 200)

;; Successful response, return it to the caller by using

;; the given response channel.

(do (put! response-chan response)

(close! response-chan))

;; Failing response, any attempts left?

(if (> (:attempts retry-options) 1)

;; Try again, decrease attempts by one and increase timeout

(network-request

response-chan

request-options

{:timeout (+ (:timeout retry-options) 2000)

:attempts (dec (:attempts retry-options))})

;; Return the failing response to the caller

(do (put! response-chan response)

(close! response-chan)))))]

;; Send the network request, return the response to the response-handler

(go

;; Before sending, wait for the timeout (if given)

(when-let [retry-timeout (:timeout retry-options)]

(<! (timeout retry-timeout)))

(ajax-request (merge

request-options

{:handler response-handler}))))))

In most cases, however, it is not practical to retry every single failed request. For example, if a request points to a file which was not found and returns 404, it probably does not help to try this request again. Thus, you should choose which requests you want to retry.

Cache Responses When Necessary

Caching is our friend when we want to make things work faster, but it is also a good way to help surviving with unreliable network connections. Our ultimate goal here is to avoid making requests that would probably return the same result as we got before. Caching can be used both client and server side. In most cases, we want to trust the browser and the server to handle caching by using the proper HTTP caching headers. Some cases, though, need special attention and application level optimisation.

On the client side, you could ask yourself whether making a specific request with the same parameters multiple times on short intervals is absolutely necessary. If the server is likely going to return the same answer, you might consider caching the request’s timestamp, parameters and response. If the same request is made again, with the same parameters, shortly after the previous one, you can simply return the answer from the cache, without making network requests. The downside is, of course, that the user does not get the most recent data from the server, so you should use client-side caching only when this is not a problem.

The idea is mostly the same on the server side. Caching can be used to avoid unnecessary network requests in the case when your server uses a third party API to load data for your client. Consider, for example, a case in which your client requests from your server the current weather conditions for a specific area, and your server requests this data from a third party API. Is it necessary to contact this third party API every single time a weather condition request is made? Current weather conditions are probably not going to change radically in the next two minutes, so it should be safe to store the parameters and the response for all of the weather condition requests. If a new request is made with the same parameters in a few seconds, we can safely return the cached data, as it’s likely going to be the same as the third party API would return us.

When the Worst Happens: Tell You are Offline

This tip applies especially for single page and mobile applications, in which data is requested from the server between page loads. If the requests start failing, your application is probably going to look like a bunch of loading bars or icons. Your user can switch between application pages or views, but none of them is loading because of lost network connection. This is not a good user experience. Even if we cannot prevent network requests from failing from time to time, we can at least inform the user about the situation. A simple modal dialog or information bar at the top of your application will do fine, as long as you remember to remove it when the connection has been re-established. If possible, you might also want to consider allowing the user to keep using the application offline and sending the changes to the server when possible.

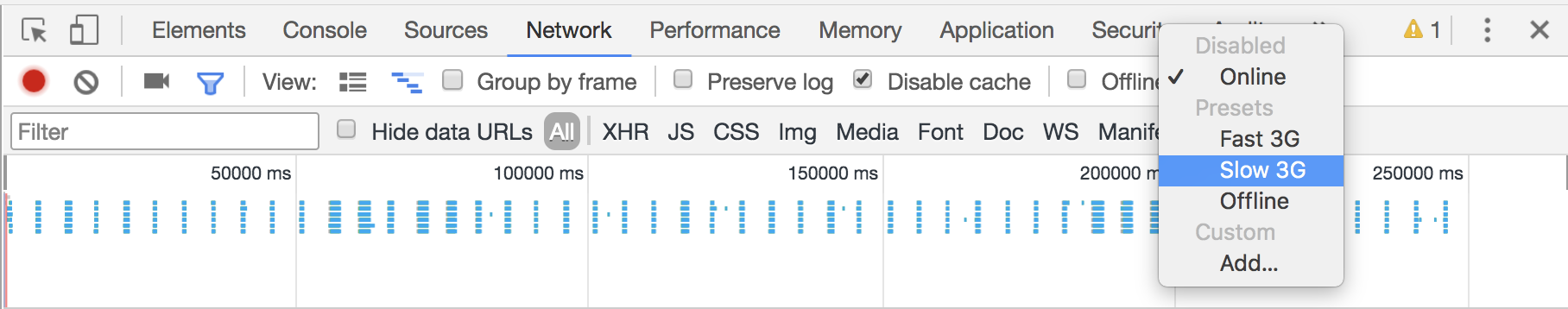

Testing Apps By Simulating Unreliable Network

Experience has shown me that we should always test how our applications work in unreliable or slow network. When developing and testing an application locally with locally installed server and database, there is almost no network latency at all and the connections are very quick. Thus, you do not really get the real end user experience.

The possible problems that you do not see with fast connections can vary. A typical problem is for example a button, which when clicked, sends a network request, and is rendered as enabled for the whole time. In most cases, the user should not be able click the button when the network request is being processed, so the button should be rendered as disabled. When the request is processed very quickly on local development environment, this is not a problem, but can result unexpected errors in production environment.

Chrome and Firefox have good network throttling tools. On Chrome, the throttling tools can be found on the Network tab, while Firefox keeps them in the responsive design mode view. These tools help you to simulate slow network connections or disconnected connection. Unfortunately these tools do not contain a feature of testing randomly failing requests, but at least you can hit the Offline button to simulate a disconnected network during the use of the application. Also, if you happen to control the backend HTTP server, you could also modify it to randomly fail some requests (in development mode, of course).

TLDR

Paying attention to handling network errors correctly is an important part of any online application development, especially if it is being hosted on unreliable network. Failure handling and recovery is a subtle art where many things depend on your application architecture. Optimising network requests, caching successful responses and retrying the failing ones a few times are proven mechanisms to make your application feel more responsive.