A Security Pipeline, or Automated security testing, is finally within our grasp! This is something we have been waiting for and trying to achieve for a number of years, but there’s finally light at the end of the tunnel. This post provides a template for automating security scans and examines various issues one will encounter implementing that. You can find the low level details covered in this post at Docker DevSec Demo repository in GitHub.

Simple: Build security in!

The basic premise for Solita is that security must be built in during the development process. There is no security fairy who can magically add security to a product when it’s almost finished. Dealing with serious security issues right before deployment to production is costly and often ruins the management’s day by postponing the launch. Or makes them sweat if they have to launch with a system which is known to be vulnerable to hackers and cyber criminals.

We have previously covered this issue in high level at this previous post What is DevSec. There was also a talk about this in Tampere Goes Agile 2017, slides here.

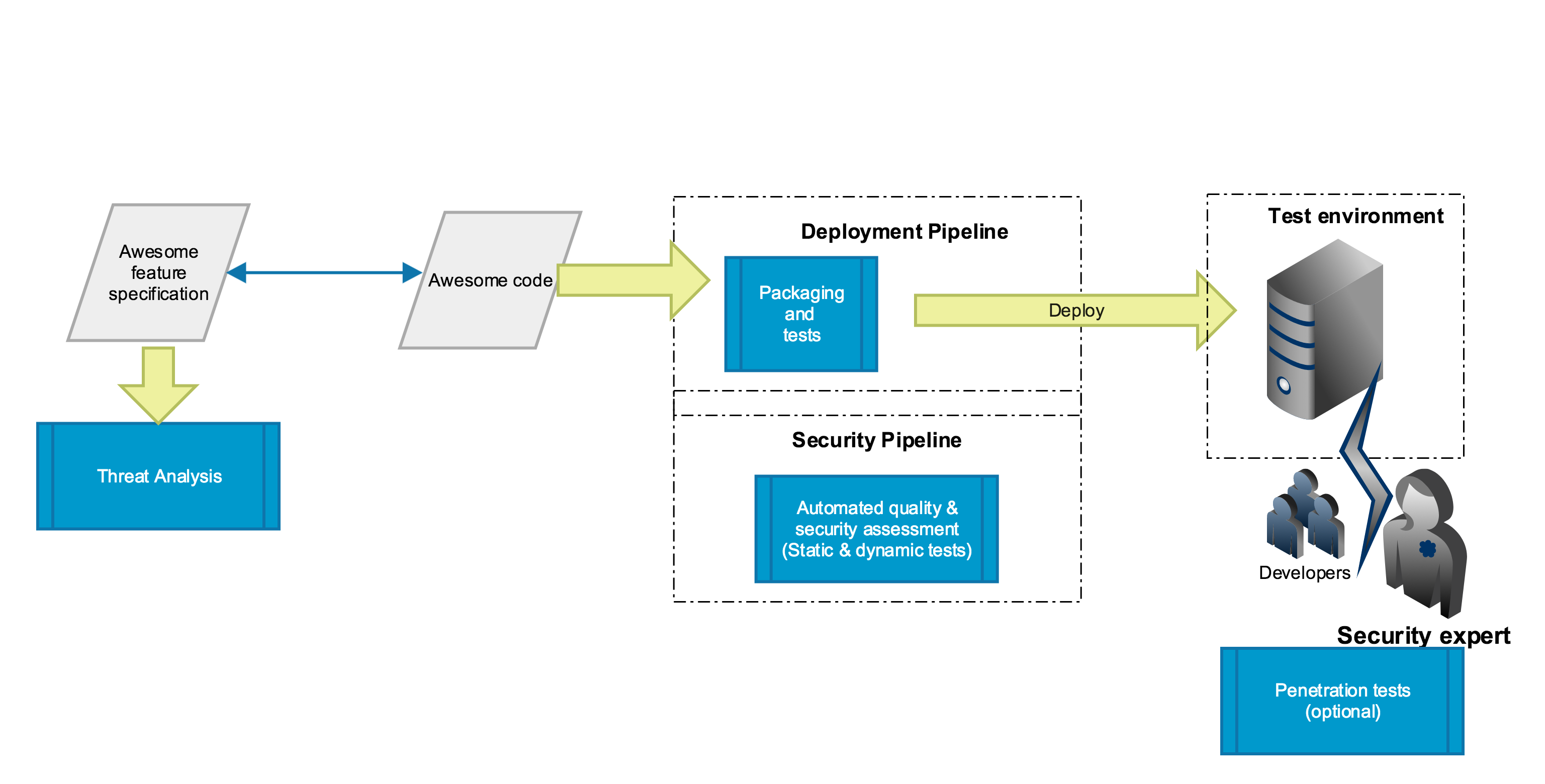

Our method is essentially a three step process:

- Ensure that the processes are reasonable and support making software secure.

- Do a threat analysis (all hands on deck, PO, customer and development team).

- Based on the threat analysis, create appropriate controls and plan security verification effort.

The last one is where automated security testing can help. By automating certain parts of the security testing we can reduce risk and get better quality product for free. That’s the idea, but of course in reality there are issues to deal with and still there is no silver bullet.

The high level view looks like this:

This is very similar to what OWASP Helsinki has attempted at their DevSecOps Hackathon, but their results are not available publicly. At least not yet.

Practicalities - Who and How?

Having embraced DevOps & DevSec & DevSecOps one has a team capable of creating scripts, automation and developers who can act as part-time security experts. These people can automate the testing using various tools. Depending on one’s choice of technologies our toolset may not be the best, but this works reasonably well for Java projects.

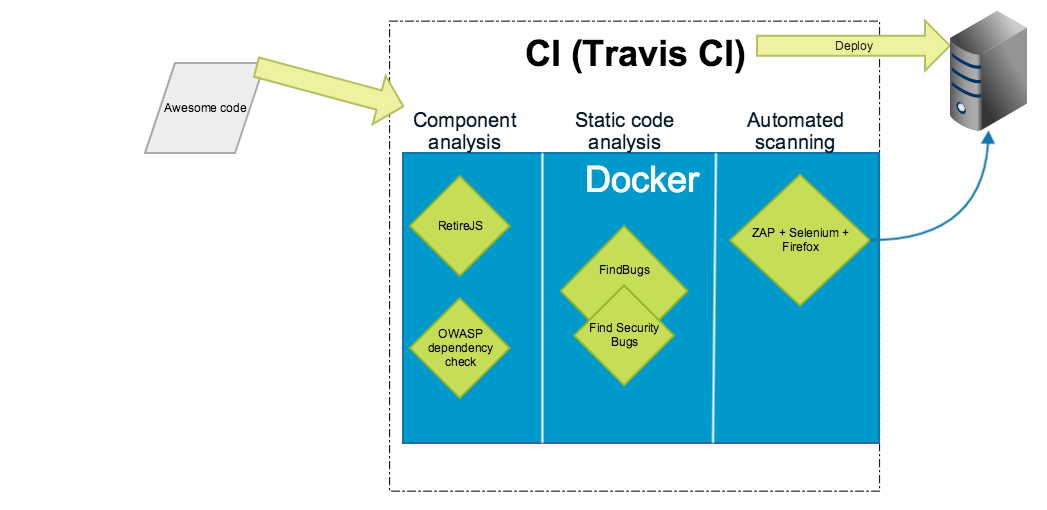

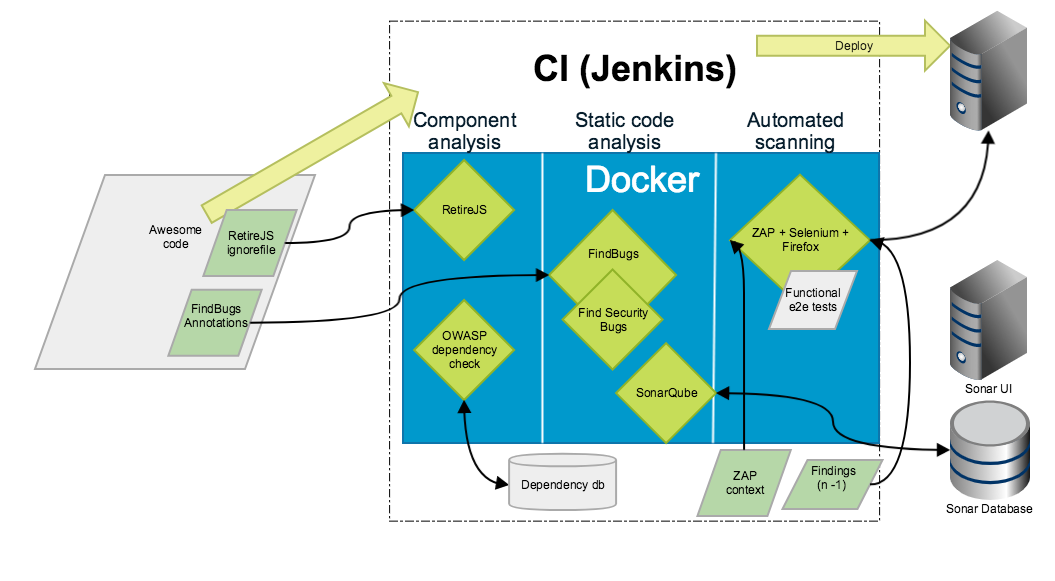

Here’s what we have done.

There are three reasons for using Docker here instead of direct Jenkins plugins:

- Docker shields the Jenkins server from becoming unstable because of new dependencies.

- It is quite easy to run the same scripts and tools on developer’s laptop or in other CI servers.

- It is a bit faster to setup the build without clicking around the UI with various plugins.

Uploading and hosting the reports

Obviously the reports are not useful inside the Docker container. In the PoC project I upload the documents from Travis to Amazon S3 bucket. Another easy option would be to use Jenkins as a web server hosting the reports.

See this previous post about documentation pipeline for reference about doing this.

Authorization with OWASP ZAP

This is one of the problems with real use scenarios. There is now support for at least two approaches:

- HTTP header based authentication (similar to how many SSO products interface to back-end system)

- Form based authentication.

To do form based authentication I recommend creating the ZAP context manually and then importing it with zap-cli.

As for the header based authentication one could write a script for that. The essential part is to provide a callback for requests like this.

function proxyRequest(msg) {

println('proxyRequest called for url=' + msg.getRequestHeader().getURI().toString())

msg.getRequestHeader().setHeader("user-auth", "test-user")

return true

}

The complete example zap-header.js script.

False positives

False positives are a constant issue with all automated checkers. There are essentially three strategies to deal with those pesky false positives.

- Exclude some files from the analysis using some sort of ignore mechanism.

- Mark some findings as “known issues” to exclude them from the report.

- Concentrate the analysis on difference between the current and previous analysis to see what are the new findings not present in the previous version.

All of these are valid strategies, but they all have some drawbacks. They all need some sort of state as input to tune the report, which leads us to a new headache, leaky Docker abstractions.

Mum, my Docker abstraction is leaking

Docker is a nice abstraction, to make these tools work reasonably, we need some sort of state outside the Docker container. This is not a major problem in most cases - if you are operating with simple files (like ZAP context, which is an XML file), you can persist them in version control system and feed them as input to Docker using volume mounts.

In the case of SonarQube it gets annoying. Sonar would like to have a relational database and setting one up is not a trivial task. Not too much to ask for in a bigger project, but definitely more work than exposing some directory in a file system.

Should I use this as the benchmark?

No. There are many other tools and depending on what you are doing, FindBugs might not be useful to you at all. We use different approach for our .NET projects, see .NET slides for some ideas. However, these three aspects should be tested (preferably automatically) regardless of your language of choice:

- component / dependency analysis

- static analysis of source code

- application scanning

The scanning is especially important as the attacker can certainly scan your application without your permission. If you don’t scan it, someone with malicious intent certainly will. So better do it first and be safe.