Especially among us software developers, “process” is some what of a curse word in many occasions. Personally I find that in most of those cases this repulsion is justified. Mainly because what processes mean to many people working in the field mean, is something that basically just hinders everyday work, something that has been dictated from above and that the people with boots on the ground have little to no possibility to affect.

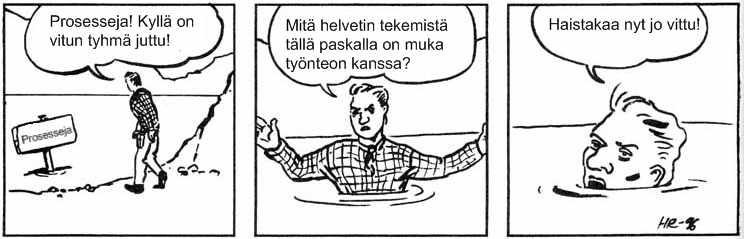

Free translation: “Processes! That’s really f***ing stupid!” “What the hell has this s**t to do with work?” “F**k you already!”

Free translation: “Processes! That’s really f***ing stupid!” “What the hell has this s**t to do with work?” “F**k you already!”

Then again in order to ease parts of the everyday work and especially the co-operation with other people, we need at least some sort of structure. This is pretty much one of the key purposes of all the main methodologies and processes. There are tons of good books, blog posts and articles on the issue so I’m not going to dwell on them for much longer. Instead I’m going to tell a real life story of how our team has approached the matter.

In many cases, when starting off with a new project at Solita, we’re not actually given that much as in terms of predicated means of how to conduct our everyday work. Some things like tech stack might be restricted by the customer’s needs or environments. Other things like financial contracts will of course have an effect on e.g. deadlines, work estimates etc. But the only unspoken rule is: Serve the customer to the best of your abilities, within the boundaries defined by the contract and in a manner that is in the customer’s and the company’s best interest. The rest is more or less left for the team to figure out.

To be honest, at first I actually was scared as hell of all this horrible freedom at first, because there was so little to lean on. I would be lying if I said that there still aren’t days when I would rather be able to just to colour inside the pre-given lines. This is because in most cases if something is going sideways with our project, you pretty much can only look in the mirror. But I’ve seriously grown to think that this kind of balance between autonomy and responsibility is definitely the most sane way of working: Giving the power and freedom to change close to every aspect of the everyday work to the people actually doing it.

I started to work on the Harja project almost 3 years ago. The project itself is a large web based open-source service (Harja@GitHub) ordered by the Finnish Transport Agency. The service itself is used for planning and monitoring road and waterway maintenance and care. In the beginning, we started with something that’s close to a “classic” scrum model as our very basic outline. This was mainly because most of us were quite familiar with it and had positive experience in previous projects. Quite soon we started to notice things here and there that didn’t make sense and were starting to feel painful, such as over booked sprints, badly defined tasks, review sessions that didn’t really give much value.

From the very beginning we’ve thought of our processes and ways of working as “snapshots in time”, which serve the current needs of the team, project, service and customer. Obviously all of these are volatile by nature and therefore we found that we needed to have a mechanism to adapt to these changes time and a time again.

For us, one of the key solutions came from regularly held agile retrospectives. Not that this would be any kind of a revolutionary method, but the idea behind it gave us a chance to iteratively monitor and change our way of working. From very early days of our project, we’ve followed the following mantra:

- Reflect on the past period of time: Observe what doesn’t work and needs to be changed and what does and has to be protected and nurtured.

- Design the changes that you as a team agree that would be beneficial. This phase requires extra care, so that the actions are very thoroughly defined, they have set responsible people and schedule, conditions which have to be met and finally a defined reason why this action will be taken. (This phase is heavily affected by S.M.A.R.T. goals)

- Take the actions and implement them. At this phase the key is to incorporate the changes just like you would any other development issue. For us this meant that the development actions are simply written as JIRA tickets and placed on our board.

- In the next retrospective, go through all of the actions and see:

- if they’ve had the wanted effect

- if they require more work

- if they we’re a bad idea just scrap them, for there can be no love for ineffective actions

As mentioned before, this is not by far close to any kind of rocket science. Though this way of thinking and working has affected a whole range of aspects in our project work, from building our CI-pipeline and making it more robust to improving our quality assurance to finding better ways to communicate with our client. For more concrete outcomes, that have gone through this very process you can find from the following blog posts: