Although the performance of JavaScript applications has increased considerably over the past few years, the language still suffers from one important limitation: all executable code is processed in a single thread. JavaScript can make asynchronous function calls, which may seem to act like they were run in a separate thread, but in fact asynchronous function calls are enqueued for the JavaScript event loop. The function is dequeued whenever the main UI thread is ready to process it.

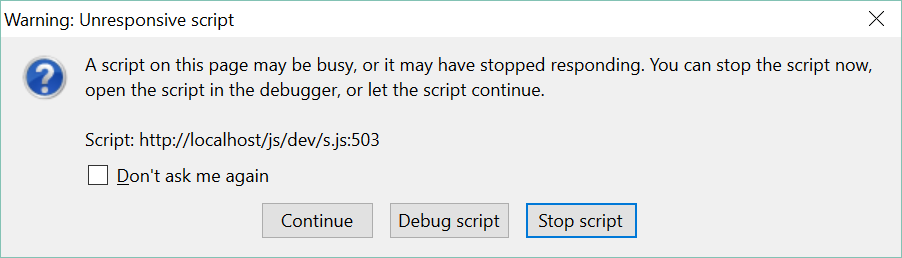

Single-threaded JavaScript is easy to work with as long as there are not too many callback functions that fire at the same time. However, single-threading also makes it impossible to execute long running tasks on the web browser without making the UI unresponsive. Do you remember ever seeing the error message below?

Long-running tasks block the UI

Long-running tasks block the UI

This message is basically always originated from the single-threaded nature of JavaScript; executing long running tasks on the main UI thread always causes the UI to freeze. You simply have to wait for the main UI thread to finish its job, while at the same time the rest of your 7 logical CPU cores are resting without a job.

But why do we need concurrency anyway? I believe most of the current JavaScript applications don’t contain and do not necessarily need a multi-threaded architecture. However, the possibilities of modern web applications have introduced a need to execute heavy computational tasks on the frontend that were previously executed on the server side. Examples of these are real-time image processing, encryption and processing big server payloads.

Web workers save the day!

Luckily things are getting better. HTML5 provides a facility to create real multi-threaded applications in JavaScript. This concept is called web workers and it is already well supported in all major web browsers. Creating web workers allows you to handle large tasks while ensuring that your app still remains responsive.

Problem solved? Not quite. There are some important limitations in web workers. Web worker scripts are almost completely separated from the main thread. In fact, they normally run in a separate JavaScript file (although it is possible to create inline workers). This makes it difficult to share context; for example web workers cannot directly access the DOM or share data between each other. They also heavily rely on callback functions on sending and receiving messages between them and the main UI thread, which can sometimes be difficult to handle properly.

Concurrency and ClojureScript

I have used ClojureScript, a Clojure to JavaScript compiler, almost one year to develop web applications. I have seen how it smartly abstracts away many of the pitfalls that JavaScript has. When it comes to making asynchronous function calls, ClojureScript has almost eliminated the need for callback functions using go blocks and channels, which act like new threads but are internally implemented using JavaScript’s regular timeouts and callback functions.

ClojureScript does not natively provide real multi-threading capability due to the single-threaded architecture of is host environment. As we saw, regular JavaScript Web workers have their pitfalls, which is why I wanted to find out if there is a way to do real concurrency with ClojureScript using Web workers under the hood.

Enter Servant

Perhaps the best known library for using Web workers in ClojureScript is Servant, which “seeks to give you the good parts (of web workers), without any of the bad parts”. Web workers are indeed called servants in the Servant library. To start using servants, we first have to define a web worker pool:

(ns app.workers

(:require

[cljs.core.async :refer [chan close! timeout put!]]

[servant.core :as servant]

[servant.worker :as worker]

[clojure.string :as string]

[cljs-time.core :as t])

(:require-macros [cljs.core.async.macros :as m :refer [go]]

[servant.macros :refer [defservantfn]]))

(def worker-count 2)

(def worker-script "/main.js") ; Name and location of the output script

Servant initialises all web workers at once and keeps them available in a pool. This is probably a good thing, since creating new web workers on demand is computationally heavy operation and requires instantiating a new JavaScript VM for each new thread. Luckily, the defined size of the worker pool does not limit you from asking Servant to spawn more threads than there are free workers, the request simply halts until free workers come available.

(when-not (servant/webworker?)

(def servant-channel (servant/spawn-servants worker-count worker-script)))

Another interesting point is that the main UI thread and web worker thread both have the same single entry point, so we have to make sure that web workers do not spawn new servants or do other things they are not allowed to do. This may seem confusing but the idea is to give both the main UI thread and web workers the same context, meaning that both of them can call functions in the same file.

Using servants for calculating prime numbers

I tested servants by developing a simple application which calculates the first 20 000 prime numbers using two different algorithms. I wanted to know which one of them is faster to compute.

(defn prime-algorithm-1 [start end]

(let [prime? (fn [number]

(cond

(= number 1) false

(= number 2) true

:default (not-any? zero? (map #(rem number %)

(range 2 number)))))

prime-numbers (keep #(when (prime? %) %) (range start end))]

(string/join ", " prime-numbers)))

(defn prime-algorithm-2 [start end]

(let [prime? (fn [number]

(cond

(= number 1) false

(= number 2) true

:default (empty?

(keep

#(when (= (rem number %) 0)

%)

(range 2 number)))))

prime-numbers (keep #(when (prime? %) %) (range start end))]

(string/join ", " prime-numbers)))

To spawn threads for running the algorithms, the following code is used:

(def calculation-result (atom {1 nil

2 nil}))

(defn window-load []

(letfn [(test-algorithm [algorithm-id]

(go (let [start-time (t/now)

response (<! (servant/servant-thread

servant-channel servant/standard-message

calculate-prime-numbers algorithm-id 1 20000))

end-time (t/now)

calculation-time (t/in-millis (t/interval

start-time

end-time))]

(.log js/console (str "Algorithm "

algorithm-id

" took: "

calculation-time

"ms to complete. Result: " response))

(reset! calculation-result

(assoc @calculation-result

algorithm-id

calculation-time)))))]

(test-algorithm 1)

(test-algorithm 2)))

(if (servant/webworker?)

(worker/bootstrap)

(set! (.-onload js/window) window-load))

For those who have used ClojureScript’s go blocks this should look familiar to you. On the bottom we separate the main UI thread and worker thread from each other. If a worker thread executes this file, we simply ask it to run its setup code. For the main UI thread we give a task to kick off the servants by spawning a new thread for each prime number calculation algorithm. We also measure the time it takes to execute each of the algorithms. Once servant thread finishes its calculation, it returns the answer to a channel, which the main UI thread then uses to read the answer and put in to an atom.

Let’s take a look at the calculate-prime-numbers function that we give to the servants.

(defservantfn calculate-prime-numbers [algorithm-id start end]

(.log js/console (str "Starting computing prime numbers in thread " algorithm-id))

(let [algorithms {1 prime-algorithm-1

2 prime-algorithm-2}

asked-algorithm (get algorithms algorithm-id)]

(asked-algorithm start end)))

The function is defined using Servant’s special defservantfn macro. Under the hood it simply creates a normal function, but also tells Servant to remember it. In the function body we simply choose the algorithm to be executed in this Servant. One of the limitations of Servant is also presented here: it was not possible to simply give the pure algorithm function for servant as an argument. Instead I had to choose and call it manually.

(add-watch calculation-result :result-watcher

(fn [_ _ _ new]

(let [result (vals new)]

(when (not-any? nil? result)

(.log js/console "Average computation time: "

(.toFixed (/ (reduce + result) (count result)) 2))))))

Finally, I wanted to know the average calculation time between the two algorithms. To do this I created a watcher, which calls a function when the atom being watched is reset. The function checks whether both algorithm calculation threads have completed their job and inserted the end result to this atom. If so, the function prints out the average calculation time.

With all the code presented above we have a working multi-threaded ClojureScript application. With it we can calculate the first 20 000 prime numbers using two different algorithms without freezing the UI. How awesome! Can you guess which algorithm was faster?

How it went

To be honest, developing this test application required a lot of trial and error before I was able to get it working. I believe most of the problems I faced were not directly related to Servant itself but were caused by the limitations of the underlying JavaScript technology. For example, I noticed that I was unable to return a normal Clojure vector from servants simply because Clojure vectors are represented as JavaScript Objects and Web workers cannot return Objects to the main UI thread. The same problem happened when I tried to directly give the algorithm function to servants.

At the early stages of the development I also noticed that I was unable to get the app working in a development mode with :optimizations set to :none. A few users on the project’s GitHub page also confirmed this problem. Because of this I was unable to use Figwheel which made the development process a bit slow.

Conclusion

I really liked the way how Servant abstracted away JavaScript’s Web workers by introducing a concept that was very close to ClojureScript’s own go blocks and channel reading. Unfortunately, I cannot say Servant was able to completely hide JavaScript under the hood as I hoped and it caused me some confusion during the development. Still I believe moving to a multi-threaded Web is a thing to be excited about. In fact, we are already there, and ClojureScript also has support for making pretty nifty multi-threaded applications despite of the limitations of the host environment.