If you wonder how to prioritize the work items in a software project and turn to the web or literature for help, most advice will fall into one of two camps:

-

There’s no difference between missing features and bugs (a lack of a bug fix is just a missing feature). All tasks should be prioritized based on their value to the stakeholders. After all, it makes no difference to the end user whether their problem is caused by a missing (or ill-conceived) feature or a programming error.

-

There’s a profound difference between missing features and defects. All bugs should be dealt with as soon as possible and they should take priority over any new feature development.

These views seem to contradict each other, but there’s a lot of truth to both. The only reason they seem incompatible is that we tend to overlook most of the costs that bugs carry. Once we account for them, bug fixing often becomes the most valuable activity we can engage in.

In this article I hope to bring to light some costs of bugs that often go ignored.

A bug or a feature?

The word “bug” means different things to different people, so let me make clear what I mean when I talk about bugs:

A bug is behavior in a computer system that its developers did not intend, or absence of behavior that the developers did intend.

With this definition, a bug and a problem are two completely different things. A computer system may contain bugs that never cause any problems. Another system may cause problems despite working exactly as intended (the road to hell is paved with good intentions).

Missed? Not if that’s the spot the archer was aiming for. Image by

RyAwesome

Missed? Not if that’s the spot the archer was aiming for. Image by

RyAwesome

This is not the one true definition of a bug – there’s no such thing – but it’s the one I find the most useful. It draws a clear line between the things we want to do (the new features and changes), and our failures in doing them (the bugs).

A bug’s life

If debugging is the process of removing bugs, then programming must be the process of putting them in.

– Edsger W. Dijkstra

To look at bugs in more detail, we need a model for where they come from. I’ll borrow one from Why Programs Fail by Andreas Zeller:

-

The chain of events that leads to a bug begins when a developer creates a defect, an error in program code or configuration.

-

If the defective code is executed or the defective configuration is loaded, it may cause an infection, an error in the program state.

-

Operations performed on the infected parts of the state may lead to further corruption, thus propagating the infection.

-

Some operations performed on the infected parts of the state may fail in a way that can be observed externally as a bug.

There’s more to bugs than meets the eye

It’s important to understand that when you see a bug, you’re not looking at a defect (a programming error). What you see is a symptom of some defect or interaction between several defects, and the infection may have been propagating for quite some time before causing the failure you’ve observed.

The bug you see may be relatively minor – just causing a slight inconvenience, or affecting just a tiny number of users – but until you have traced your way back to the defect and analyzed it, you have no way of knowing for sure what bugs the defect may cause and when.

“Don’t worry, honey! It’s just a little triangle, the kids can swim around

it!” Image by Christian Haugen

“Don’t worry, honey! It’s just a little triangle, the kids can swim around

it!” Image by Christian Haugen

Most infections never cause other failures, but some propagate aggressively and cause bugs much worse than the one you’ve observed. The more users a piece of code has, the more parts of the program state a defect can infect, and the bigger the chance that the same defect causes several different bugs. A defect in a library can cause all kinds of bugs in different programs altogether.

Sometimes a bug with little impact may be the easiest way to track down a defect with much worse consequences – even before they’ve materialized.

To fix, or not to fix

There are many legitimate reasons why you might choose not to fix a bug. Here are just some of them:

-

The defect is in third-party code and you’d rather wait for a fix than write a costly workaround.

-

Users may have become dependent on the buggy behavior. This can especially be the case if the defect is in library code.

-

Any change to the defective code would risk introducing much worse bugs.

-

The defect has to do with interaction with a poorly specified system, and coming up with a fix would require too much expensive trial and error.

-

Fixing the defect would require deep architectural changes, making it too expensive.

What all these reasons have in common is that, to make an informed decision about whether or not to fix a bug, you have to know what the defect is and where it is located. For most bugs, at that point you’ve done 95% of the work and might as well just fix the defect. (In fact, until you’ve changed the code and seen the bug disappear, you can’t be sure you’re even looking at the right defect.)

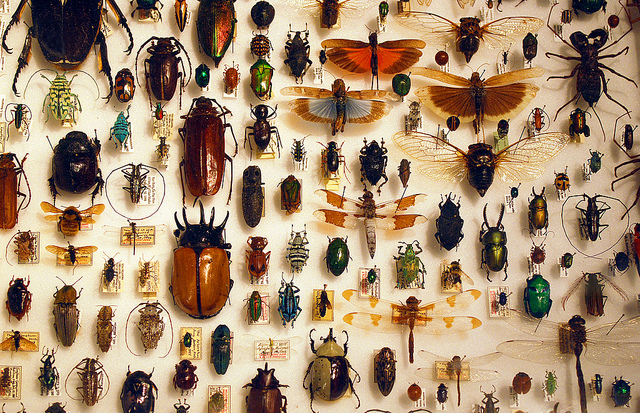

Image by Barta IV

Image by Barta IV

There are even some cases in which it may make sense to ignore a bug without locating the defect first:

-

You cannot reproduce the bug even in the same environment in which it’s reported to have occurred. The chance of an invalid bug report is too high to justify investing more time in reproduction.

-

The defect is clearly presentational (e.g. the CSS is invalid for some browser). It’s very unlikely for an infection to spread deeper into the program and cause worse failures.

Be very careful before you decide that a bug must have such a harmless cause that it’s not even worth finding! Many defects are caused by invalid assumptions. Those same assumptions will lead you astray when you think about what the defect might be.

Here’s what David J. Agans writes about jumping to conclusions in his book Debugging:

“Quit thinking and look.” I make this statement to engineers more often than any other piece of debugging advice. […] While we think up all sorts of nifty things, there are more ways for something to be broken than even the most imaginative engineer can imagine. So why do we imagine we can find the problem by thinking about it? Because we’re engineers and thinking is easier than looking.

[…]

I once worked with a guy who was pretty sharp and took great pride in both his ability to think logically and his understanding of our products. When he heard about a bug, he would regularly say, “I bet it’s a such-and-such problem.” I always told him I would take the bet. We never put money on it, and it’s too bad – I would have won almost every time. He was smart and he understood the system, but he didn’t look at the failure and therefore didn’t have nearly enough information to figure it out.

The bug factory

Remember when I said that bugs are caused by infections caused by defects caused by a programming error? That’s not the whole story.

Most programmers work to the best of their ability, yet end up creating defects. Since the errors are out of the programmers’ control, it may seem that defects (and thus bugs) just happen to be a fact of life and there’s nothing anyone can do about it. This is not the case.

Image by RIA Novosti

Image by RIA Novosti

A programmer is always a part of a complex system of people, tools, processes, and practices, all interacting to give rise to (among other things) a software system and all its defects. The system can prevent mistakes, or it can drive the programmer to make more of them.

When each programmer is doing their best, it’s the system that determines the amount of defects ending up in the software. And if they’re doing a half-hearted job, it’s probably the system that’s discouraging them.

If we make a bug go away but leave in the defect, the defect will soon manifest as another bug. If we fix defects but never touch the conditions that gave rise to them, it’s just a matter of time before someone adds new defects just like the ones we fixed, perhaps in a place where they can do even more damage.

It’s like bailing water from a leaky boat. It might get the boat dry for a little while, but as long as the leak’s there, you’re never done bailing – and whenever you’re bailing, you’re not rowing.

What to do about the situation depends on your priorities. If you don’t care about the boat and there’s just a little way to go, it might make sense to focus on the rowing and let the boat fill up. If there’s a bit longer to go, you might need to take bailing breaks from the rowing so the boat doesn’t fill up before you reach your destination. But to go as fast as possible for a long time, you need to plug the leaks.

Plugging the leaks

There’s an infinite number of ways in which software can be produced, and no two systems that produce it are the same. Only someone who knows a system can see how it can and should be changed to prevent or reduce a type of defect (hopefully without too many unintended consequences). What makes things better in one setting can make them worse in another.

Just like with debugging, if you guess at the source of a problem without observing it for long enough, there’s a good chance you’ll jump to the wrong conclusion. Changing your process every time you discover a defect is like adjusting your sights every time you miss a shot. You just end up making things worse.

Usually it’s better to just make a note of every time a defect seems to hint at a deeper issue. Once you begin to see negative patterns, you can start experimenting with changes to make them go away.

Image by Hans Splinter

Image by Hans Splinter

I can’t tell you what changes should be introduced to your system, but to give you some idea of what they might look like, I can list a few examples of the kinds of changes that have helped bring the defect rate down in the projects that I’ve worked on.

If you’re lucky, you can prevent a type of defect with a code-level solution without making any big-picture changes to the way you produce software. This includes things like type systems, static verification tools, design patterns, refactoring, and so on:

A stray

console.log()broke a feature on old Internet Explorer browsers. We wrote a test that checked all JavaScript sources and failed if it found a call toconsole.log(). Similar tests were used to ensure more complex invariants on source code level.

There are defects that can’t be prevented with a technical solution but can be reduced by changing the process:

We kept finding obvious mistakes in the source code, so we started doing lightweight code reviews before closing any Jira issue. The original programmer walked the reviewer through the source code on the programmer’s machine, with a typical review lasting around 5-10 minutes. We also started using pair programming for the most complex tasks.

When defects are born out of poor communication, you may have to make changes that, at first glance, seem to have nothing to do with programming:

When the project began, the team members were seated in different rooms and even on different floors. Moving the whole team into the same room greatly improved the quality of communication and our sense of collective code ownership.

I hope these examples have given you an idea of the huge variety of ways in which you can change prevent, or at least reduce, various kinds of defects.

You’ll never plug all the holes in the boat, but you can reduce the leak down to a trickle and your bailing to the occasional scoop instead of the constant struggle to keep your head above water that it too often is.