With iOS and Android sharing most of the smartphone market (and Windows Phone relegated to marginal status with a few other players) there is ever less incentive to create cross-platform applications. Rather, it is better to pick a lead platform and do your first implementation on that to collect feedback. The best features can then be improved and bad ones discarded when you bring your application to “the other platform”.

There are differing schools of thought as to whether you should pick iOS or Android as your lead platform, and there is no definitive answer. It depends on your target demographic, the features you want to have, and many other things. Here I’m working on the assumption that picking iOS as the lead is generally a smart thing to do, as it allows you to work with a fairly homogeneous environment (at least compared to Android), and allows for constant innovation. Apple is able to roll out new versions of iOS quickly, so most customers will quickly get on board with a new release, and you can raise the minimum required iOS version of your application.

Stuck with Objective-C

Until very recently, almost all iOS (and OS X) applications have been developed in Objective-C using Apple’s Xcode. Other tools like REALbasic (now Xojo) and Xamarin have found some success, but ultimately the platform and Xcode are so deeply entwined that learning Objective-C has been the path of least resistance, especially if you want to stay abreast of the latest developments.

My first brush with Objective-C for the Mac in 2005 was a little bewildering. Here was a language that was C-compatible but object-oriented, with a weird, verbose syntax reminiscent of Smalltalk. It also had a quirky manual memory management system requiring intense concentration. Still, after using it a while something kind of clicked, and I began to like it. That may have also been due to the fact that it was the only feasible way to develop applications for the Mac, and would be even more important for the iPhone in 2008.

Over the years Apple made many improvements to Objective-C, including Automatic Reference Counting (ARC) for memory management, a nicer syntax for object literals in version 2.0, a new compiler, the block syntax (well, maybe not actually an improvement) and a Java-like iterative for loop syntax and dot notation. Still you couldn’t help thinking that Objective-C was gradually getting a little long in the tooth. At least I thought that after thousands of lines of Objective-C it was time for something else.

Enter Swift

Seasoned iOS developers and newcomers alike were pleasantly surprised, but also a little puzzled, by Apple’s announcement of the Swift programming language in last year’s World Wide Developer Conference (WWDC 2014). There have been concerns that Objective-C is hard to learn, even though there is no problem in supporting large production apps using the Foundation and Cocoa frameworks. However, the language is a little arcane by modern standards, and the occasional need to use frameworks that are not even Objective-C, but plain old C (like Core Foundation) may be a little too much for new and casual app developers, which the iOS platform continues to attract.

For many iOS developers the latter half of 2014 was a mad scramble to get acquainted with Swift, and to get popular iOS frameworks to play ball with Swith projects, or rewrite them in Swift. Tools like CocoaPods took some time to gain Swift compatibility, while Apple kept refining the language with successive releases of Xcode. Especially Swift 1.2, which shipped with Xcode 6.3 in February 2015, was a major, somewhat backwards-incompatible release. It fixed a lot of annoyances and brought Swift closer to prime time.

In WWDC 2015 this past June, Apple announced the customary new versions of OS X, iOS and Swift, along with a new Xcode toolset. Currently iOS 9 and Xcode 7 are in beta, and the final versions will ship in the fall - with Swift 2.0, which will also be open sourced. Apple has made it very clear that Swift is the future for iOS and OS X development.

The radical conservative language

As programming languages go, Swift is both radical and conservative. It takes the best ideas and paradigms from many existing programming languages, and mixes them together into a distinctly Apple-flavored cocktail. The most radical ideas of Swift relate to the type system. There is strong type checking with powerful type inference (both concepts almost straight out of Haskell). Indeed, the influences and design decisions behind Swift have been documented by Chris Lattner (Swift and LLVM lead).

Most newcomers to Swift will struggle with the most forward-thinking concept of the language: optionals. It is a simple enough concept: a variable either has a value or it hasn’t. This notion has been around for some time in mainstream programming languages like C#, and also more fringe ones such as Scala, but along with it come new annoyances like the need to unwrap optionals.

Swift is a relatively big language, with a lot of syntax inherited from the C family of block-structured languages, but stripped of unnecessary noise like semicolons and parentheses. Compilers have become smart enough to be able to figure out what goes where without the programmer pointing out obvious things like expression boundaries.

A very simple way of summing up all the odd numbers in an array using Swift looks something like this:

let series = [ 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21,

34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610 ]

var totalOdds = 0

for term in series {

if term % 2 != 0 {

totalOdds += term

}

}

print(totalOdds)

You can copy and paste this code as it is, and run it in an Xcode playground.

Since by now there are countless web pages that present Swift from multiple angles, and there is also excellent documentation from Apple, along with an official Swift blog, there is little point in delving any deeper into Swift syntax here. Still you can see Swift’s type inference at work, and a lot less punctuation than you’re likely used to.

Fun on the playground

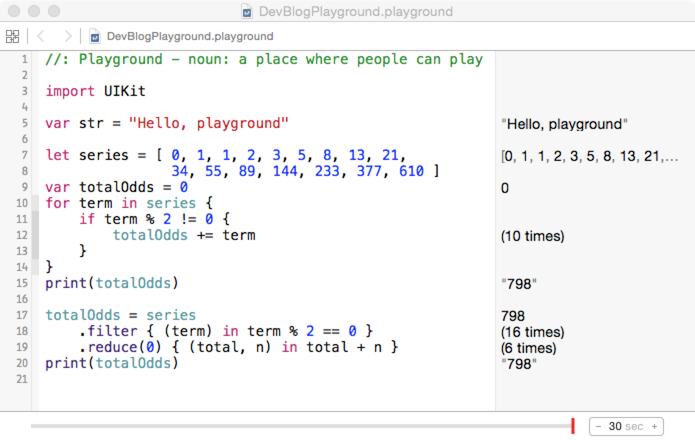

Learning Swift is easy with the playgrounds introduced in Xcode 6. Essentially playgrounds are interactive workspaces in the manner of IPython. There is also a REPL for quick experimentation, and with the Xcode command-line tools you can even write shell scripts in Swift, but if you haven’t tried playgrounds, prepare to have your mind blown.

Playgrounds are responsible for some of the most impressive interactive programming experiences I’ve had for a long time. Many academic teaching environments have pursued similar goals, but Apple has combined a production-capable toolset and a fun way of learning by doing. You should definitely check out playgrounds when exploring new Swift features.

There are some tricks you need to master if you start prototyping actual application

code in a playground. For example, asynchronous networking can be frustrating

to try if you don’t know about the XCPlayground framework and the

XCPSetExecutionShouldContinueIndefinitely function. (Now you know.)

A playground can show you the values of variables and more. Here you can see the previous summing example as it appears in the playground:

Functional Swift

Here at Solita, functional programming is quite well established, with several Clojure projects in production. Therefore I’ve developed a special interest in the functional aspects of Swift. It is by no means primarily a functional programming language, but many of the key concepts, such as higher-order functions, programming with values, and closures, are well supported.

One of the biggest differences with mainstream programming languages is the

pervasive use of immutable values in Swift. Indeed, you should take a page

from the functional programming playbook and start using structs and let

as much as possible, instead

of classes and var, since it helps to keep things straight in an increasingly

multithreaded environment. Immutability is a paradigm you can use even if you

don’t do full-blown functional programming (yet).

The Swift standard library

has a number of functions providing basic functional-style

replacements for traditional loop-based iteration of array-like structures,

namely map, filter and reduce. By internalising these concepts you can

make your code more elegant and less cluttered.

Here is an actual example of a mobile client application for rail traffic data, filtering out trains by type from an array (slightly simplified from production code):

let filteredTrains = trains!.filter({ $0.trainCategory == "Commuter" || $0.trainCategory == "Long-distance" })

In Objective-C, the standard way of filtering an array is traditionally quite verbose in comparison:

NSMutableArray *filteredTrains = [NSMutableArray array];

for (Train *train in trains) {

if ([train.trainCategory isEqualToString:@"Commuter"] ||

[train.trainCategory isEqualToString:@"LongDistance"]) {

[filteredTrains addObject:train];

}

}

You could also use an NSPredicate and a block, but that introduces two new concepts

and does not make the source code any more concise. Perhaps the greatest single

improvement in this instance is the fact that you don’t need to use isEqualToString

anymore to compare strings in Swift.

For a functional way of summing the odd numbers like above in Swift, try this:

let series = [ 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21,

34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, 610 ]

var totalOdds = series

.filter { (term) in term % 2 == 0 }

.reduce(0) { (total, n) in total + n }

println(totalOdds)

This looks quite incomprehensible at first, but if you break it down with the

help of a playground, you can see that the array is filtered down to six elements,

which are then summed together starting with zero. Of the three basic tools –

map, filter and reduce – the reduce function is most difficult to understand,

but not much more than Quicksort, which also seems unintuitive at first.

Ready for prime time

Until now, using Swift for production code has been a little bit of a calculated risk. You have been amply warned about potential breaking changes as the language evolves, but it is still an annoyance to rewrite your source when a new version lands.

Swift is about to reach critical mass with version 2.0 and iOS 9 on the iPhone and iPad, and to lesser extent with OS X El Capitan on the Mac (and the potential of OS X desktop software should not be ignored).

So far I’ve been involved with two serious Swift projects at Solita. A client for our open data API for Finnish rail traffic, started in Objective-C, was quickly converted to Swift when version 1.2 of the language was released, and was a great opportunity to learn how to use new or converted third-party frameworks like Alamofire and the Swift version of JSONJoy.

Most recently I’ve been developing a utility for registering company visitors, with iBeacons installed in all our company offices to help detect your proximity. The app utilises new third-party Swift open source projects like XCGLogger, SwiftHTTP and SwiftyUserDefaults. (I just wish that everybody would stop using the Swift name or a derivative of it as part of the project name.)

At this time, I would not hesitate to start a new iOS development project with Swift, even though Objective-C projects are still supported in Xcode, and will be for a long time. New Objective-C code continues to be written, and there is no harm in that, but most of the instructional material from Apple and others is moving forward and over to Swift, so if you want to learn about new frameworks added to iOS 9 and OS X – and write applications for watchOS – you will have an advantage if you know Swift.