In my current project we have multiple projects that depend on each other. There are some libraries that are used by multiple projects and some projects whose web services are called by other projects. We even have a diamond dependency. The versions that are deployed from each project should be compatible with other deployed projects.

The goal now is to implement continuous delivery (or even just continuous integration done well). The first step is to make each build produce binaries with unique version numbers, as I have written earlier, and then make all the build pipelines use the latest versions produced by upstream build pipelines. Preferably it should also be possible to handpick the versions of the various projects, in case you don’t want to deploy the latest of some project.

As a proof of concept I created the interdependent build pipelines for three of these projects using ThoughtWorks Go. I got it all working in one day, but the other team members didn’t consider Go’s free edition adequate and considered the price tag too high (we have 20+ team members and multiple build agents) (Update: Go is now fully open source, so the original argument is no more valid), so I set to do a proof of concept using Jenkins. After a couple of days of research and experimentation I think I found a compromise that might work.

Though there are many build pipeline articles about Jenkins, none of those I found matched our use case of multiple interdependent projects. Most of them just had a simple linear pipeline, maybe with a diamond dependency here and there. Even Stack Overflow gave no answer.

In Go, the downstream pipelines receive as environment variables the information about all upstream pipelines, which makes it easy get access to the version number and binaries of the dependee projects. So I was looking for something that lets you pass information in a similar way transitively through many Jenkins jobs. After wading through lots of plugins I found a hint of something that could emulate the desired behavior.

Configuration

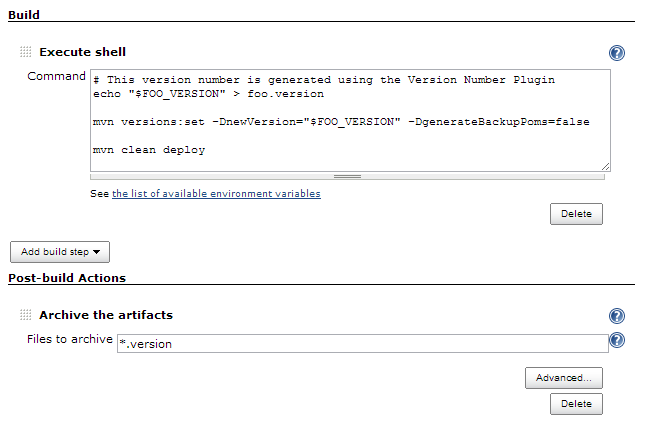

Here is what you would do in an upstream project:

- Generate the version number for the current build, for example with Version Number Plugin or a custom shell script.

- Write the version number to a file, e.g.

echo "$FOO_VERSION" > foo.version - Set the version number to the project, build it and save the binaries in a repository (either an external repository or using Jenkins’ archiving). In Maven the version number can be set with mvn versions:set.

- Configure Jenkins to archive the

*.versionartifacts after the build is finished. - Trigger the immediate downstream projects.

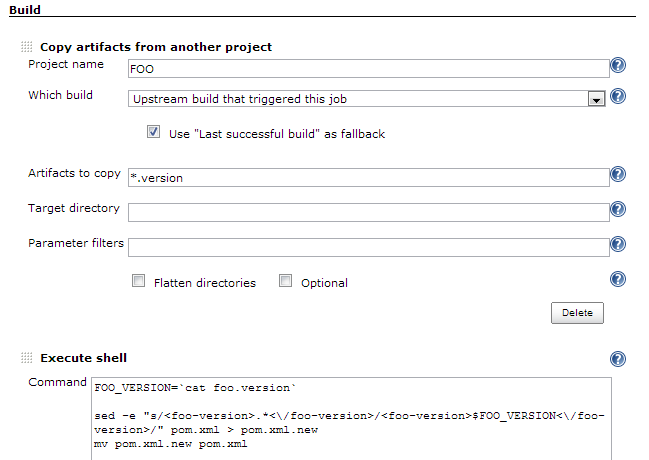

Then in a downstream project you would use the Copy Artifact Plugin to get access to that version number information. The thing that makes it possible to use this plugin, is using both the Upstream build that triggered this project and Use “Last successful build” as fallback options together. The downstream projects can be triggered independently of their upstream projects, typically due to a commit to the downstream project, and there can be multiple builds building in parallel, so both of those options are necessary.

Here is how you would configure the downstream project:

- Use the Copy Artifact Plugin to copy the

*.versionartifacts from the upstream projects. Select the Upstream build that triggered this project and Use “Last successful build” as fallback options. - Read the version number from the file, e.g.

FOO_VERSION=`cat foo.version` - Set the version number to the project’s dependency information. If you need to edit XML, prefer using a scripting language with XML support, but when everything else fails, there are regular expressions:

sed -e "s/<foo-version>.*<\/foo-version>/<foo-version>$FOO_VERSION<\/foo-version>/" pom.xml > pom.xml.new && mv pom.xml.new pom.xml - Build the project so that the build tool retrieves the dependencies from whatever repository you put them in.

If you have lots of such projects chained together, then the projects in the middle would have both the upstream and downstream configurations. The use of a common naming pattern *.version for the version metadata will archive in each project its own version number and its dependencies’ version numbers transitively. That may be useful in seeing what versions are included in a build. It may also be used to detect a diamond dependency problem and fail the build if it happens.

Conclusions

The above setup at least makes it possible to create non-trivial build pipelines in Jenkins. The configuration feels like a hack and it makes it hard to choose a particular upstream build to use (e.g. when deploying). Also I don’t think that Jenkins can handle fan-out and fan-in intelligently; the Join Plugin works only for simple situations and also the Build Flow Plugin seems too limited.

I would choose Go any day over Jenkins when there are multiple projects that closely depend on each other. But if need be, something like this might let you avoid changing your CI tool. Jenkins has lots of plugins, but the plugin quality varies widely, though there is always the option of writing your own plugin. Go doesn’t support plugins, but it has a REST API and I hear plugins are on its roadmap.