How much does an algorithm cost? What’s the work estimate for function that calculates value-added tax for a price? How many euros does it cost to produce? It does not sound too complicated, right? Any monkey could write that function within one hour of good concentrated work, right?

Wrong.

This article is not about getting a good bargain for a software product. This is also not about doing stuff with great existing components, or using a low-code/no-code approach to solve a repeating problem with a reusable answer. This blog is about being careful with the invisible costs of piling features on top of each other’s and using all the shortcuts to get there.

Here’s the 15-minute version. Will it work? Maybe… How do we know?

// This is 15 minutes and done! Yihaa!

function vatCalc (a) {

let b = 20;

let c = (a/100)*(b+100);

return c;

}

// TODO: Fix this

Did you try it with decimal numbers? More than 2 digits? What precision we would like to have? Where did that VAT percentage of 20 come from? Would this work in an international application? Do the VAT rates change ever? What if the VAT rate is a decimal number? What if someone tries to pass in a zero or negative value? What do the variables mean? And most importantly, what was the original developer smoking when writing this one?

Also: Which devices should this software work on? How it should be tested? Which countries, cultures, languages, timezones? Do they affect this? How about security and privacy? This will be part of something larger, probably, not living in isolation.

Total cost of bugs

Let’s start with bugs. The origin of the word comes from actual insects, getting stuck inside complex machinery. Nowadays, instead of insects, we have programming mistakes or oversights. They tend to hide within imprecisely communicated requirements. They feed on added complexity, and they reproduce within a human’s imperfect mind. The human brain works on varying levels of efficiency, depending for example on caffeine levels in the blood, ability to concentrate on a task, and of course on what is the general motivation at the moment.

In other words: Sure, you can write an iteration of the code in 15 minutes. But it might have a bug or two, a blind spot where it fails to work. VAT is a pretty simple algorithm - perhaps you copied it from the vastness of the Stackoverflow, congratulated yourself, and moved on. And now that off-by-one error or bad rounding rule due to using double type for money caused a massive mistake in a one-time payment or huge accumulation of small errors over months and years.

What I’m pointing out here is that everyone makes mistakes. People are imperfect, even the most perfect ones. They are easily distracted, by any interruptions or even their worries and desires. An average coder has perhaps 15 minutes of clarity a day, during which perfect code is made. The rest of the day is filled with sneaky bugs.

There are some bugs in the history of computer sciences that had a devastating cost. For example year 2k bugs - relatively small things, people cutting corners, then realizing it is too big an issue to be fixed within normal coding, so they kind of decided to avoid thinking about it. Eventually, it needed fixing, and the estimated cost of those fixes and issues that were left unfixed was in the ballpark of 500 billion dollars. For example, Mariner 1 spacecraft - minor bug vaporized 18.5 million dollars. Fortunately, Mariner 2 worked better. Mars Climate Orbiter in 1999, NASA used the metric system, Lockheed Martin used imperial units. Result: Probe lowered 50km too low, collapsed in the atmosphere, and burned 193 million dollars of money in an instant, not to mention original scientific work that was planned. Bugs might end up costing especially much when they affect physical things, have an effect on people’s health and lives, money, or privacy. But to this day I’ve yet to see a software project where the result would be meaningless and do not affect anything whether it’s working properly or not.

Making the bugs cheap

Fortunately, there’s an easy answer to making bugs much cheaper. It’s the rapid feedback loop. How much does a bug cost? It depends on when it is found.

- I found it immediately while writing the code because I was caffeinated and had my smart pants on. Price of the bug: 0$ (not counting the pants and coffee)

- My teammate noticed the bug when we were pair programming the algorithm. Price of the bug: Still pretty much 0$ - of course, pair programming costs money, too, unless two heads are together more productive altogether than two separate ones.

- My relentless TDD principles caused me to detect the bug when I was writing the unit test for the algorithm. I wrote another test to catch the bug, then wrote some code to fix it. Cost: perhaps a few dollars now, I do have to spend a bit of time to write both the code and the tests. On the other hand, tests work as a specification of how I intended the code to work, so they might work as part of the documentation as well.

- Our QA team knows how severe bugs can be, and they have a great mind for finding ones. They found this one. However, it now took longer, so fixing the bug is a bigger task, I need to coordinate the releases, write some tickets and explanations, have the fix retested, do handoffs, etc. Let’s say price if a few hundred bucks here, or more if the process is not optimal and I have to do task switching a lot.

- Bug got to the production environment and caused an incident immediately. The cost is pretty much the same as above, but since this was triggered by angry customer feedback, this just became more severe and heavy fix, so add zero to costs. Also, these bugs come with PR cost as well: Lots of severe bugs - or hardly any bugs? Add another zero to cost.

- Bug got to the production environment but was sneaky enough to only be detected a lot later, like in the above examples. The cost just went up again. It may have caused havoc already, that’s hard to fix. Fixing the actual bug can also be more expensive, first one needs to find it, understand it, and fix it. It might be that development has ended and the original team has moved on, and now new people are frantically trying to find/read/understand any documentation left over. Do we have working automation going on, or is fixing bugs probably going to cause new bugs? Add as many zeros as you like.

So you probably got the point. It’s cost-effective to fix bugs early. Lots of agile principles, especially ones from Extreme Programming origins, can help with that. Talented engineers these days apply them because they understand this.

But what just happened to work estimates that we started this article with?

- How long it takes to write the code?

- And to include at least satisfactory test automation?

- And to make sure we also have good coverage?

- And to refactor it, so architecture stays clean, readable, and something we can expand?

- And to pair program or pair review the code, so that every line is checked by four eyeballs instead of two?

- To make sure that the documentation is satisfactory so it can be maintained by other teams when necessary?

- To make sure we have continuous deployment capability, both technically, and process-wise, so that we do not have to fear making changes, to fix bugs and to refactor code that’s already being used

- To make sure code is secure by design: Not having vulnerabilities to obvious well-known attacks since SQL/XML/JavaScript/whatever -injection, cross-site scripting, etc. It’s much cheaper to audit/hack yourself constantly than to wait for an external audit, a lot of handoffs, and task switching later.

- To make sure GDPR privacy rules are being followed, not broken. The cost here can be up to 20 million euros or more, much more.

So, what’s the realistic estimate now for that component? And which one would you rather buy? There is probably a good middle-ground to be found, depending on what problem the software is trying to solve. But no matter what is the need, I would not myself be tempted to try luck-driven development.

So in the end it is about balancing money, time, and features. But also how well you want those features to be done.

Lifecycle of a software solution

One important thing to consider is of course the lifecycle expectancy of your software solution. If you are writing something that is expected to be used for few years, or few decades, the cost ratio of development to operations is very different, and then decisions you make on the quality and flexibility might be, as well. It might be ridiculous to try to cut corners during the development if that cost is a fraction of the total cost to run the software. If we are creating something that should be around for a long time, it’s especially important to avoid cutting too many corners, and instead create something that at least starts its life clean, refactored, documented, easy to understand, easy to modify, easy to maintain.

I’ve sometimes been tasked to create software purely for a marketing campaign, that is expected to run for a limited amount of time. Perhaps after that, some parts can be recycled to a new campaign, but in those cases, it was not necessary to keep it clean, so … go wild, I guess. Put that cowboy hat on and forget about refactoring and test automation. Other times, I’ve been involved in some POC projects, where we want to build rapidly and cheaply something that proves just enough to get the funding and vision for the real thing. Again, make it quick, make it dirty, as long as everybody understands that and is not stupid enough to use that steaming pile of ugliness as the basis for the real thing - just recycle the ideas, vision, and conviction, and keep the codebase ugly.

Understand the lifecycle of what you are building. Are you creating a product, are you creating a long-running service, or a quick-and-dirty demo/POC/campaign app, one-short, with a limited lifetime. Don’t bring a hammer into a pillow party, or vice versa.

And do note that this is not just about bugs, this is also about how easy the code is to maintain, and how flexible it is to make changes when requirements change on a longer run. And this is also about how to find new talent to recruit so we can maintain the code on the longer run, without driving people insane.

A colleague of mine wrote an excellent article on technical debt - which is what you get when you just keep on piling features in a hurry, never fixing issues that arise, or refactoring code to try to battle the increasing complexity. You can go read it here: 6 Easy Steps to Boost the Creation of Technical Debt in your Organization.

The thing is again: By taking those shortcuts every day you think you are producing faster, but you are instead only being messier. And the cost of all those shortcuts will become visible when development has been done for some time, or when development has ended and software or service is being mostly maintained with as little effort as possible. So trying to be lazy and fast will eventually make you, and everyone working on that codebase, miserable and extremely slow.

So, can I still have it cheap? Pretty please?

Yes, you can.

Now that you reached this point, I will reveal a secret. Cheap is not a problem. Making shortcuts is the problem. You can find cheap by applying agile, and remembering that we’re still doing about 80% of unnecessary ambitious features only 20% of people need, if even that. Scrum and Kanban as well as Lean are good ways to concentrate on the essential, perhaps do fewer features, but do them properly. I’m always inspired by how much money Google has made using just one input box on an HTML form - but doing it in an ingeniously engineered way.

So I would rather keep on doing excellent input boxes that drive the business and are well and professionally made, than that fast-coded cowboy-style PHP webshop that pretty much causes disaster after another. Actually, during my career, I’ve been brought more than once to salvage the steaming remains of unprofessionally coded steaming pile of cow manure. You can imagine how much it costs to have to do that in a hurry. Oh, and it’s not always PHP, either :)

Another thing to keep in mind is getting the requirements right. It’s very difficult to do before we start coding because that’s the moment when we know the least about challenges, limitations, and possibilities ahead. That’s why all agile methodologies tend to shine bright because we delay making decisions as late as we can. On the other hand, this requires good refactoring, it’s essential to keep the codebase in good health, flexible even. And of course, maintaining your codebase adds to expenses at that point.

Naturally, a high price does not guarantee excellent results, either. An agile project that does not have a vision or focus or worthy goal can be a horror story. And is a super coder that much better investment than just a damn good one? Hard to say. How do you evaluate quality?

Well, perhaps that’s a great topic for another blog in the future… :)

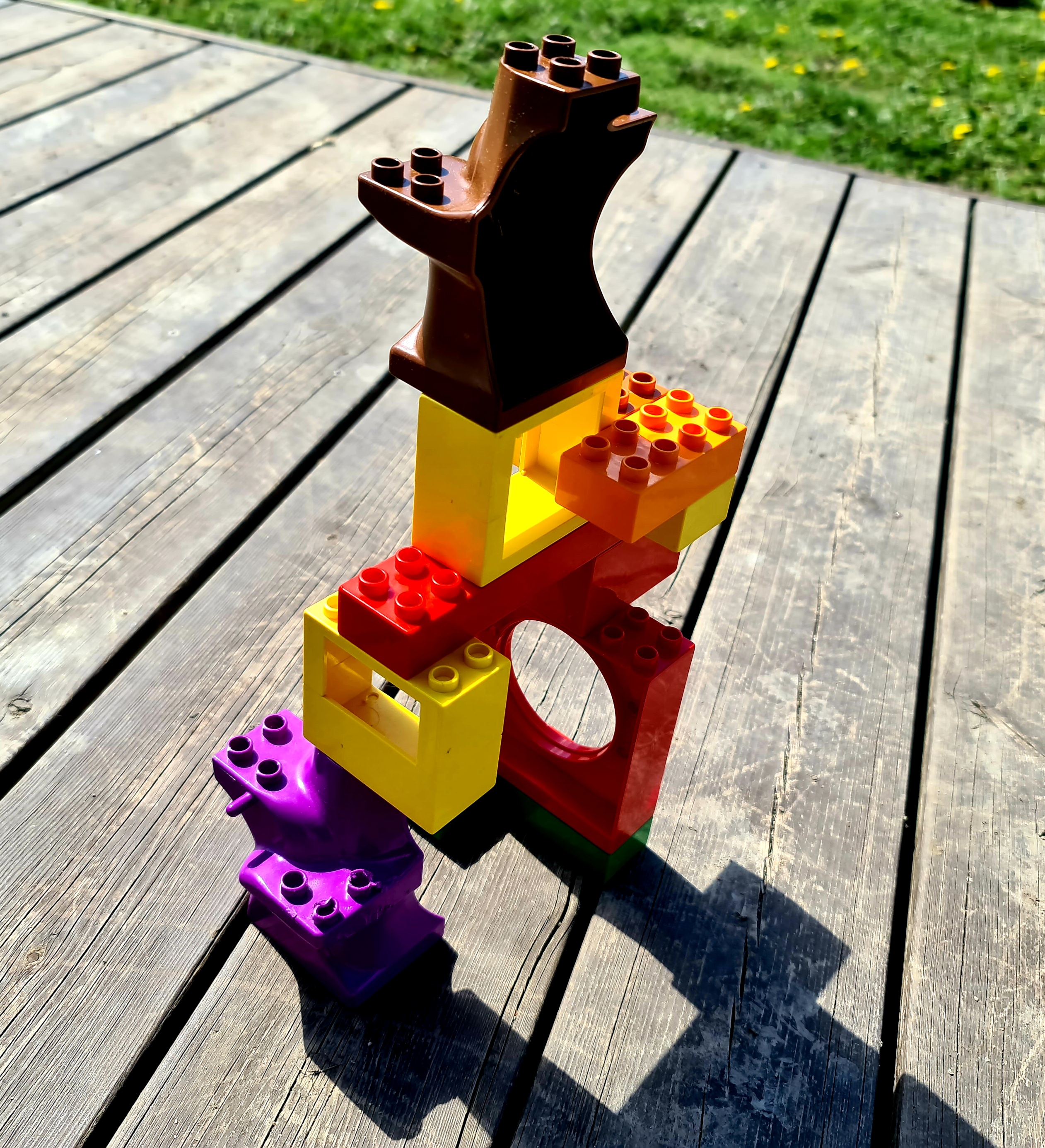

You can have 10 balls

Here is a jar of colorful balls. Let’s say you get 10 of them. Each represents 1/10 of your available resources to implement something. You get to choose how you wish to distribute them.

- Of course, you can opt all-in for features. 10 balls for features, maximum speed, no tests, no auditing, no reviews, no security checks or guarantees of any kind, no changes in design while coding.

- Or should you invest one or two of those balls for security? Implement a secure development lifecycle as a colleague blogged about recently in How to implement a secure software development lifecycle. - might make sense to have at least one, perhaps more depending on how big a risk a security or privacy breach could be in your application. How about security monitoring? Automated tools for security checks? Constant automated or manual audits? Secure development practices? Saferoom to work in? Penetration testing, bug bounties? Making sure personally identifiable information is handled as it should be all through the process and resulting application? Incident response processes? How many balls should be assigned here?

- How about investing some for automation in general? Automated delivery pipelines, checked every day, automated testing. You can do minimal test automation, or go heavy for it, unit testing, integration/API testing, end-to-end testing, security testing, validating configurations and infrastructure templates, static source code analysis, quality metrics, etc. It’s your choice and should depend on the expected lifecycle of the application. But if you think about investing none, remove three balls from total immediately, because you will be drowning in bugs and manual work as software starts getting farther.

- How about quality in general? Principles like pair programming, pair review, team review, sharing information across teams all come with a cost. Paying off technical debt constantly, refactoring to keep solution maintainable, maintaining that test automation too, evolving architecture as new needs are revealed, all come with a cost, but also benefits. How many balls here? If you are tempted to assign none, remove four balls from the total because you will probably not even be able to continue coding for long before succumbing under the disaster that is spaghetti code.

- How about user experience, usability, design? If this is Internet-facing service on a field where there are other players, all that solid tech on the background doesn’t benefit you a lot, if you cannot get users to use your service, instead of other choices. So if you are selling something, you would probably want your user experience to be easy and enticing, as opposed to hard, glitchy, and unpleasant. If you are not competing, ease of use might come with benefits such as better quality of data that is collected, fewer human errors that might cost a lot to fix later. What kind of application or service are we building here? How many balls for UX?

- How about disaster recovery plans, designing, implementing and testing backups, infrastructure as code, processes? It depends on how tolerant your skin is for disasters without a plan.

- And how many balls to assign for documentation, information transfer, continuity?

So, as you can see, the implication here is that balls represent your resources during a sprint, because in agile projects we typically build the good stuff in all the time, along the way, once we understand more. Perhaps you can see that building good quality costs more money than just writing the code itself. You might end up still having 10 feature balls. Or just 1 feature ball, with a lot of automation, security, user experience, and continuity built-in. Or more typically, something in between the extremes.

There are many ways how you can play it here. You can get more features, of course, by cutting from quality aspects. But in the long run that typically does not work. You can redesign or cut some features, or make them optional, to buy some allocation for the quality. But there are limits to that as well. You can naturally increase the total allocation, add more balls, but that represents more money and possibly time, which has its limits as well. But in the end, this is all about having good transparency and finding the perfect balance for your particular needs.

Conclusion

If you have an endless supply of money and time, you’ve got it made, you will eventually get what you were looking for. If you have a huge supply of money and time, and only a very limited set of features to do, again you’re good. I haven’t seen these kinds of projects yet, though. In my experience, projects come with a lot of hopes and desires, and typically very limited budget with them, possibly also with a deadline set in stone and coming up soon. So if you are in that situation, this advice might apply to you.

Have a clear vision, find the real value

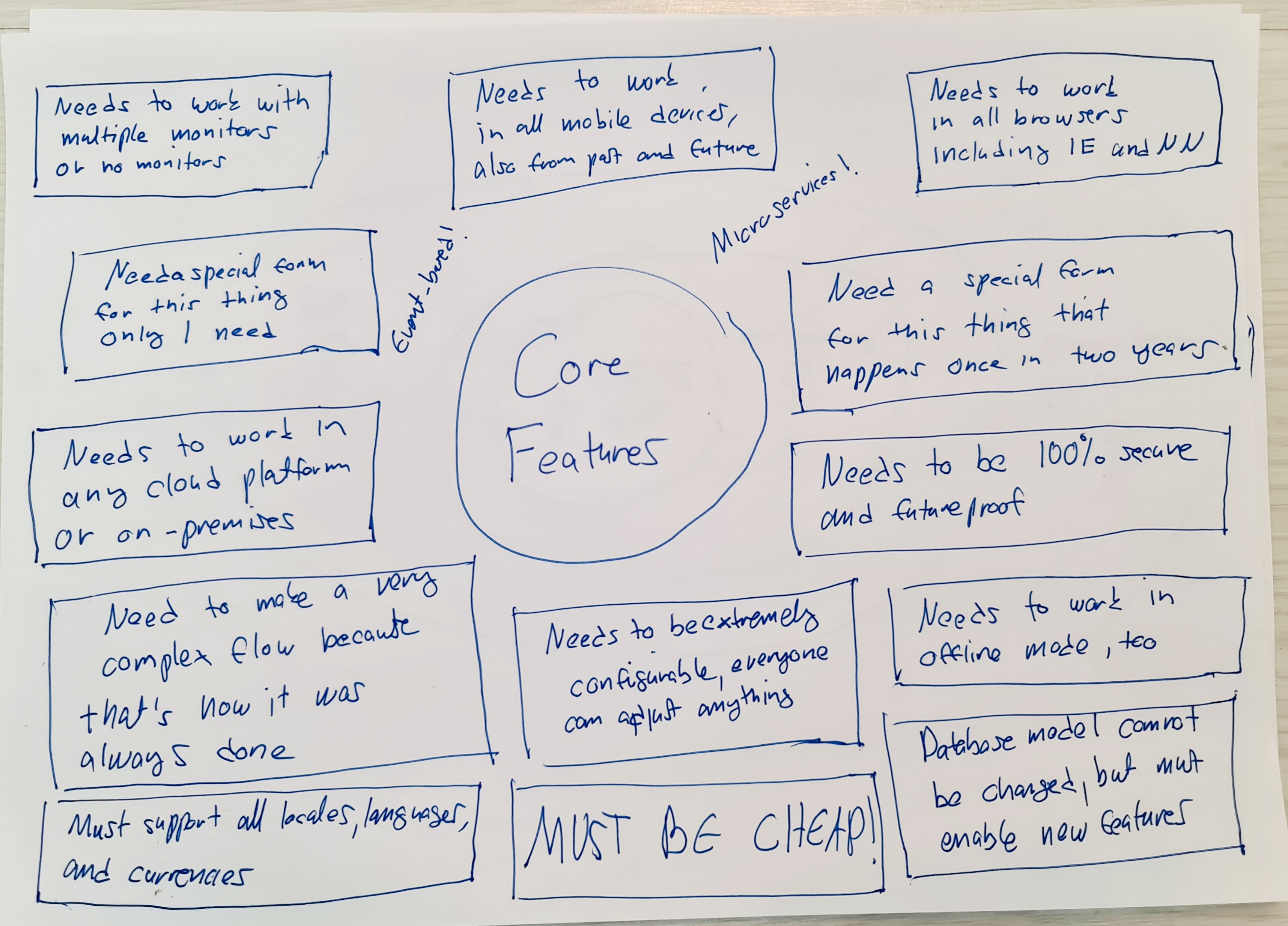

Try to cut hard any features that might be nice but not necessary. There are often things that are only used by a tiny minority, or brought along for legacy reasons. Or requirements that sound nice but come with a hefty cost. Cross-cutting requirements like which devices will be supported increase cost for every feature that you will build, so their cost sneaks up on you. If they are essential, then let’s do them, but be aware of the cost. Sometimes software development projects take place too late, only when there’s an absolute need to do something. This might cause the feature list to include multiple decades worth of wishes. In that case, it might be a good thing to instead of trying to do them all and perhaps fail badly, to pick a suitable set of essentials, do something about them, and try to return to the others another time. If you manage to resolve 10 important problems with a software project, it’s more valuable than trying to resolve 100 and eventually failing to improve anything.

Don’t cut corners, instead try to increase the value

While working towards that vision, don’t try to cut corners unless you absolutely need to. Cutting corners tends to get much more expensive in the long run. Either you are not getting the value you were seeking, or quality is so bad that you will pay more for years to come. Good cheap is either about getting a good bargain, an excellent discount, without losing quality. Or it can be about increasing the value you get for the money that you spend. Former is very difficult to do, especially for anything custom made. Latter can be done by thinking hard where the value comes from, then prioritizing things so you start with the things that bring the most value, and leaving the diminishing returns until later. Accept that you might not get all the things done with low priority and value, but you’ll get the most important things done well, and they will serve you for a long time.

Make sure that what you are building is done with an acceptable quality considering the lifecycle of the software solution.

Set the realistic expectation for quality

There exists an endless amount of things that could always be done better in a software project. If you try to take every quality dimension to 100%, you would probably not get anything done. So it’s essential to choose wisely what is your acceptable quality level. If it’s a small, simple project, which you expect to run only for a few years, or a one-shot marketing app, then you can cut corners more. If it’s a complex application, with lots of expensive risks, and you are envisioning a long lifecycle for running it, with constant smaller improvements along the way, then perhaps emphasize the build quality more. That being said, I think for almost all projects, the definition of done should contain things like IAC, constant refactoring, test automation, threat analysis, continuous deployment, and pair reviews, mainly to keep the development and deployment process stress-free.

Measure regularly, and check the direction

And of course, with the agile methodologies, we like to stop often, demonstrate what we have, and check the direction. It’s often possible that something that seemed important suddenly seems less important. Or something that was not thought at all rises to be essential. Or we might find a way to do an elegant shortcut that costs less and provides more or equal value to what was originally though. While we are doing the project and seeing the results evolve, our wisdom increases every week. It’s at the peak near the end of the project. If we did the prioritization well, that should be the point where all essentials were done, and we are working on tinier things that will bring some good and can still be done.

Cut that waste

And speaking of methodology, try to be lean with it as well. Avoid creating ceremonies that include everyone often but involve only a few of them. Endless meetings where only one person speaks are not a great way to use money, typically. Autonomy and empowerment tend to bring efficiency. You hire or rent excellent talents that are good at what they do, then you clearly set and communicate the value and priority, and let them loose. Demo days are great checkpoints. It’s easier to iterate and polish something tangible that you have seen than something imaginary based on a chain of imaginary steps, which can be seen differently by everyone.

So it can be done. I’ve seen it happen now dozens of times. I’ve even seen two projects where features are not set before the project, they are designed at the beginning of the project, based on a larger vision. Hopefully, we will also one day read about those in this blog. That sounds like a great way to find the value. Hopefully, reading this blog you were entertained, and perhaps got some new ideas as well, or may have different experiences. I would be happy to hear about them, you can find me in most social media channels and of course, my company email address works as well, any feedback is always much welcome.