This essay is a developer’s opinion to a topic that has been beaten to death already: how to make public calls for tenders of IT services, or software development. There certainly is no lack of writings about how you can conduct a procurement, what to do and especially what not to do. Here’s my teaser: it’s hopeless. However well you prepare, whatever you will set as the criteria, there’s always the possibility that your chosen IT supplier will not get the job done. Then you only have bad options.

It is no guarantee of quality if the supplier is expensive. It only tells that they are preparing for a lot of extra work, or big profit margins. It’s almost on the contrary, but a cheap supplier might just have totally misunderstood the scope of what you’re buying, or is otherwise delirious about their own abilities. It might help that you stick with a supplier that has a good track record, but then there is the risk that you’re actually sticking with a total douchebag supplier out of fear of change. It’s hard to assess the ability of your supplier when it’s about IT.

The fundamental problem

Why is it so hard to procure IT stuff with public tenderings? Because programs and digital services are very different from most other things you buy. First of all, at the time of procuring, it is often ill-defined what the expected “product” is. When you buy socks, it’s easy to switch to a new product, because they are drop-in replacements for each other. The closest equivalent you have in IT, is programs that implement exactly the same (probably standardised) interface, such as different LDAP servers. But for most of those standardised interfaces, open source products already exist, so most of the time it makes no sense to use money when you can get a better implementation for free.

But it doesn’t end there. For most stuff you buy, you can readily assess their worth by using them. The defects and problems of IT products become apparent very slowly and only through extensive use of the software/service. Unless your IT supplier is making deliberate effort to ensure that they are building something that actually helps you, they will be long gone by the time you have gathered enough experience to know what you should be asking for.

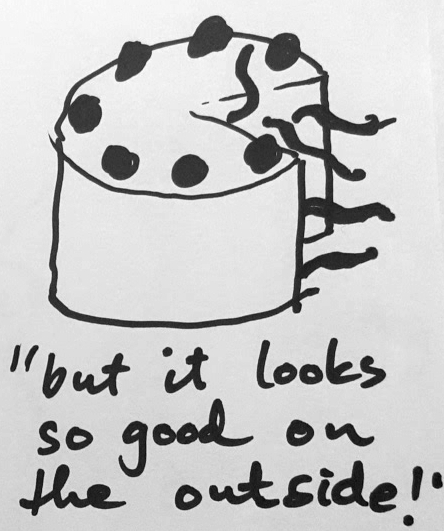

Combine this with the fact that in addition to an “outer” quality (what it looks like and whether it is easy to use), IT products also have an “inner” quality. It’s about things like, how often it will crash, do you ever lose data, how difficult the product is to update, how much resources it consumes, how difficult further development or maintenance will be, and how hard it is to integrate with other systems. Still combine this with the fact that these are systems that often hold data that is critical to the business or organisation. It is far from trivial to transfer this data to other systems. And as if that wasn’t enough, these are also systems tied to the very working of your internal processes. Your employees will specialise in the particular systems they have to use, however bad and counterproductive they might be.

Put together, all this means that you have no way of ensuring that you will get something useful for your money, but you will still be tied to that system for quite a while. As I said, it is hopeless. What will then happen, if it is hopeless? With your call for tenders, you will get what you will get. You can’t really ensure that it will be something useful, but there are some ways to ensure that it will be useless.

The partial solutions to the fundamental problem

What to avoid

There’s no lack of examples as to what will make a software project produce useless results. For instance, if the feedback cycle is too long, you will get something that doesn’t really help you. Long feedback cycles are caused by too much planning and too little trying things out. A policy that prevents automation is also very bad for productivity and software quality - for instance, hand-written installation instructions to server administrators. One pitfall is trying to procure before you have a clear understanding of what the system will at least do. Even if you have a great IT supplier and they’re doing their best, they have almost no way of succeeding in these situations.

One thing that kind of works, but is still very bad for productivity, is to make them hurt as much as you do. In practice, it means that for every defect, missed milestone, and reduction of scope, you impose a heavy penalty on your supplier. Then you will get quite precisely what you agreed on. Whether that is good, depends on how precise the understanding of your needs was at the time of contract, and whether you got that understanding into the contract properly. One downside of this approach is that, when they give offers to a tendering with heavy penalties, they will account for their risks in the price. The penalties also only work well as a threat. When things really start going awry, it is usually of little consolation to you that your supplier is in even deeper trouble than you are. In any case, a contract like this will bring about a very hostile environment, where that focus is on sticking to the contract as verbatim as possible.

What to try out

One approach is to avoid buying IT “solutions”. Instead buy brilliant people that will build those solutions and find what you actually need solutions for. Employing these people was the traditional way, but consultants will also do, as long as they are really committed to the long-term success of your organisation. However, if you are buying these people to do your IT for you, you probably don’t have much idea whether they are doing it well. That’s because it takes good IT skills to assess the IT skills of others.

Another approach is just to absolutely trust whichever IT supplier you choose, and give them as much information as possible so that they can help you. Then, if they are smart and benevolent, they will probably be able to help you. I know that my colleagues try their best, but I still can’t promise they will always succeed. We also try to tell our customers if they’re asking for impossible or insensible things, and sadly, neither can I promise that we’ll always succeed in that. But we will try!

One approach that I haven’t seen used, but which should prove interesting: implement the same system (i.e. the same user stories) in maybe two or three unrelated projects. That way, it’s easier to see the strengths and shortcomings of these different implementations. It might sound expensive, but not necessarily. Because this multiplicity works as one kind of quality control, you can let go of supplier quality criteria, such as years in business etc. This should drive the price down a lot, because your supplier market will be much more competitive when you don’t constrain your options.

One approach that mitigates the risk of software projects is to start with a working (and preferably, open sourced) software product and build up from there. This way, you should be able to have a working product in every development iteration - say, every two weeks - so progress is easier to assess. There is also a kind of plan B if you need to terminate the project early: using the software as-is. Remember, however, that the inner quality of your developed software might be really bad even if it seems good from the outside. So this is no silver bullet that will solve everything.

When the harm has already been done

What to do then, if you are already in the situation that your chosen IT supplier cannot deliver what they were supposed to, or what you would actually need? As I said, there are only bad options then, but some are worse than others. My experience is that organisations almost always underestimate the costs of finishing a bad software product or service. Like a destructive, hostile employee, a counterproductive, unautomated and unintuitive IT system can do enormous damage. It will be hard to get rid of, complicate your processes, make everybody demotivated and still get so intertwined with your business that it is very hard to eliminate. Not to mention that in forthcoming procurements, you have to take this old system into account, and prepare for extra work in the migration.

The most important “solution” here that I know of, is to fail as early as possible. It’s hard, because the organisation has already been preparing to get some kind of new service, but it’s still usually the least worst option. It doesn’t really matter very much whether you try to stay on good terms with the terminated supplier, put fines on them, or whatever aftermath there might be. Usually the greatest harm is still that you have to find a plan B to continue your processes without the new service or program you were waiting for. The earlier you fail, the smaller the consequences, but it’s never too late to cancel a project if it hasn’t been put into production.

You can try to find a new supplier to pick it up from the situation where the former supplier left things, but don’t expect wonders. If it hasn’t been working very well with the former supplier, most likely the inner quality of the software/service will be even worse than the outer quality. Even if you get a good supplier this time, they will have hard time improving the sluggish work they’re left with. There’s a limit to how much defects a given piece of software can have before all development time goes to just deal with those defects. A badly written piece of software will be enormously slower to develop new features for. You should prepare for a phase where the development is purely focused on improving the inner quality and progress is not very visible in terms of user experience or functionality.

Sometimes it really makes sense just to throw away the old work. Then the first project can be seen as a kind of prototype, or experimentation, that hopefully improved your understanding of what you are trying to get. This might prove really valuable if you decide to engage again in a similar project.

How to prepare for public tenderings

If there’s no way to ensure things will work out, what should you do in the first place? You might already guess the answer - always have a plan B that you can take even if the project fails to produce useful results. Ensure you can go back as long as you have any reason to doubt whether the new software/service can achieve what it was meant for. Ensure that you can always terminate your contract, and for whatever reason, such as bad vibes. And, if you have some pushing reason to get a new IT system, such as the old one is breaking down or reaching the end of its support cycle, try to fix that pushing reason first with minimal changes. Do not push all kinds of feature and improvement requests into an upgrade project with a hard deadline, because you will be in an enormously unpleasant situation if it fails.

It also helps a lot if your organisation has at least some people with the skills to evaluate the quality of your IT supplier and the solution they are building. That way you can fail earlier, and with less of a hassle.

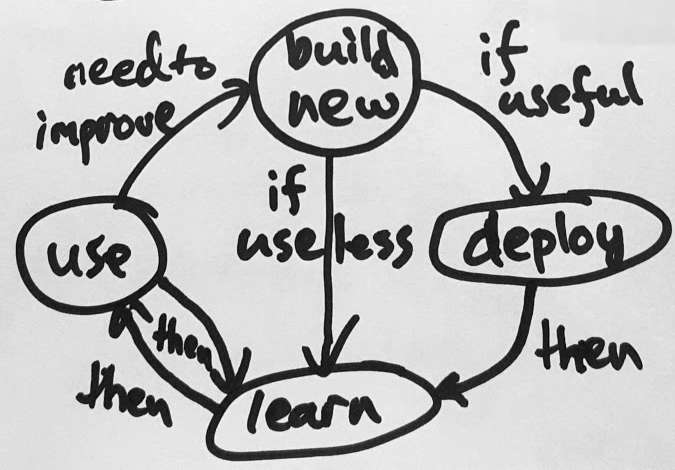

No need to be pessimistic, though! My point is that procurements should be seen as kinds of experimentation, not life-savers. They can and will fail sometimes, and when they do, they still provide valuable experience. The important thing is to get a maximum amount of experience. Treat procured software/services as a process of experimentation and do not depend on them before they have proved themselves. This way, you get a different mindframe where you only have good options: continue your business as it has been done, or get an improved way of working by deploying the new ideas in your new IT service.

Ensure you can go back. Trust your supplier. Try to get something usable as early on as possible. Try to build as much experience as possible. Sometimes you will waste money, as with most investments, but sometimes you may win big. The better you understand what you need, the better your odds at winning.