This past winter we worked together with the Finnish Transport Agency (FTA) to release railway traffic data into the wild. The resulting open data API can be found here. I feel the project was a substantial success for all parties involved, so I thought I’d share some thoughts.

Background

The rail traffic data is based on the data in LIIKE-system (link in Finnish), which is developed and maintained by Solita. LIIKE is mainly used by FTA, Finrail and operators like VR for planning rail capacity usage, controlling rail traffic etc. Briefly: it has all the train data that we could dream of. This project was part of a larger initiative in Finnish governmental organizations to release more open data.

Keep your API simple, stupid

The train data is served through a RESTful JSON API (well, it’s not REALLY RESTful, it’s just kinda RESTful). Let’s take a look at the API design.

First of all, RESTful URIs are about resources and nouns, as opposed to verbs in RPC. In our API, trains were a no-brainer for resources. So you can get the train number 1 for today’s departure from http://rata.digitraffic.fi/api/v1/live-trains/1. We have four end-points:

- /live-trains for live data

- /schedules for schedule data without live updates

- /history for schedules and actual times

- /compositions for train compositions, configuration and vehicle information.

These end-points are also resources, so you can query them without the train number. That would give you a list of trains. There is also a 5th end-point for metadata, e.g. for retrieving a list of all the stations.

All the endpoints support some kind of date query parameters, usually these are departure dates for trains. In Finland, a train number is unique for each departure date. Live-trains and schedules also support querying by train station, e.g. trains arriving/departing to/from a station or trains connecting two stations. Now, shouldn’t a train station also be a resource? The answer is: it’s debatable. In our case, since all of our endpoints essentially return a list of trains, the station is just a filter applied to this list. Filters are better suited as query parameters as opposed to resources/locators.

In general we tried to be stingy about adding extra query parameters just for filtering purposes. In short, the train of thought (no pun intended) was this: less API parameters => less code to maintain => ??? => Profit. Keeping things simple. I think the main function of an open data API is to give public the access to the data at a minimal cost for the data owner.

However, the resulting JSON responses from our API are quite big. Right now /live-trains is giving me 0,5MB compressed (which is over 8MB uncompressed) JSON goodness. That’s a lot of data to transfer and deserialize, especially on mobile devices. At the moment we have decided not to cater to mobile needs directly. Instead we are focusing on offering a simple, reliable and performant API. This does mean less parameters for filtering, leading to larger JSON-files on average. So for now developers who want to minimize data usage in their mobile apps have to add their own proxy. Sorry guys.

Another dilemma is how to serve train updates to users. Polling the full /live-trains end-point every 10 seconds isn’t viable. I also don’t like the idea of having separate streams for updates (this is how they did it in UK). We opted to go with something along the lines of “give me all the trains that have had updates since last query”. Each train in /live-trains has a version number. If you query the end-point with the version number, you get all the trains that have been updated since that version (i.e. their version number is bigger). This works nice and easy. We even get the version number directly from the Oracle database in the LIIKE-system using ORA_ROWSCN for no extra cost. Sweet!

Typically when thinking about versioning in a REST API, the first thing that comes to mind is to put the version in the URI (as in /api/v1/resource). All the cool kids say that’s just wrong and that you should use content negotiation and put the version in the accept-header. I agree with this in principle, but we still chose to go with versioned URIs. Why? Well, mostly because almost no one actually uses the accept-header style. Also because we again wanted to keep things simple. Having the version explicitly in the URI is neat and simple and it makes debugging easier (rather than having to use plug-ins in browser to insert the accept header). Concerning backwards-compatibility, our plan is to keep supporting old versions as long as they work with the newest database schema. Maybe we dug our own grave with versioned URIs, but YOLO.

Layer cake

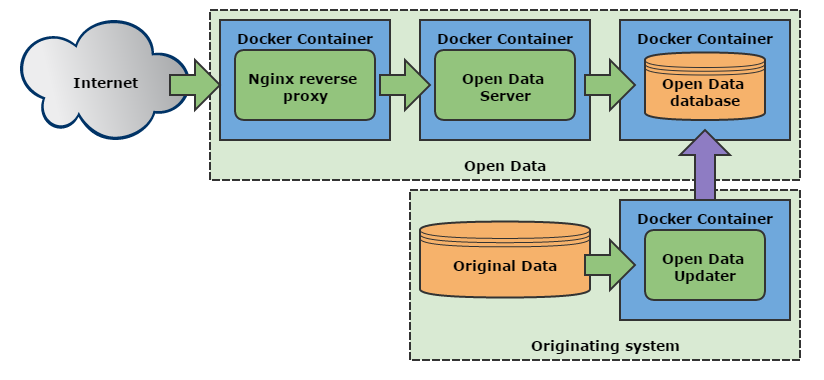

We used Docker to contain our services, because it’s the future. Docker allowed us to contain and separate all of components in a kind-of-microservices-way. On the outside we have Nginx in its own container functioning as a reverse proxy. Nginx directs all requests to Open Data Server, which is a Spring application with Jetty serving the actual API. Open Data Server gets the data from the Open Data database (MySQL). On the originating system side (LIIKE), we have the Open Data Updater which keeps reading all the updates from the actual LIIKE-database and pushing them to the Open Data database.

I think this is all very neat! The public API is separated from our originating system through several layers. The only component with write-access is the Open Data Updater. Everything else only needs a read-only access to one port in another service. From a DevOps perspective, it’s super easy to update, since we can shut down any service without affecting others and update it independently (as long as the Database schema stays the same). This was my first time running containerization in a production environment and I’m impressed how convenient everything has been. Nice and simple.

And since we are aiming for simplicity, all the data is immutable. Once a train has been updated in any way in the original database, the Open Data Updater replaces this train in the Open Data database. And with Java 8 streams, (almost) everything is immutable in the code as well.

Early on during the project I was playing around with the idea of storing the final JSON file for each train in a document database and serving the files directly from there. However, this doesn’t really make any sense since our schema is fixed and fits a relational model perfectly. Another idea was to use PostgreSQL’s JSONB datatype, but since we don’t really need to search by JSON fields there’s no real benefit. Serializing/deserializing JSON is such a marginal cost anyway. So in the end we opted to use a plain old relational database (MySQL), although we did denormalize the data some. Now each train has its own rows in each table, so replacing trains is a breeze.

Immutability on database level also makes migrations super easy. If we update the schema, we can just drop the whole database and let Open Data Updater populate it again.

Your data is bad and you should feel bad

Obviously, when moving to open data, you are coming from a closed environment (well, duh!). Our data was coming from the LIIKE-system, which is used by railway professionals for planning and operating the railway capacity. Previously closed data becoming open all of sudden is bound run into some issues.

First there will be bureaucracy. As there are several parties involved (Finnish Transport Agency, Finrail, VR etc.), the question of ‘who owns the data?’ is not clear. This results in some bureaucracy. Overall I think FTA has been doing a very good job with this. After informing all the parties in advance, FTA’s policy has been to release everything that has not been explicitly declared secret.

Even then, at the time of writing this article, we have not been able to release the positional data of the trains (other than arrivals/departures at stations). This is a bummer, since positional data is obviously of utmost interest for most users. We also can’t release composition and vehicle data for cargo trains. However, we are working actively to get more data like the positional data and train/car identification ids released. I’m sure developers will find these data points interesting.

Another issue with opening previously closed professional data, is that the needs of professionals and consumers are quite different. This became particularly clear after the first mobile apps were released and one passenger almost missed the train due to bogus forecasting data. Now, the automatic forecasting in LIIKE-system is usually a bit pessimistic, which is the opposite of what you want as a passenger. Imagine your mobile app saying the train will be departing 10 minutes late. However, often passenger trains can catch up between stations. So instead of departing 10 minutes late like your mobile app says, the train departed only 5 minutes late when you were still buying a drink at the convenience store. Not cool. Obviously we seek to improve the forecasting algorithms, but mobile app developers also need to make sure their users understand the limits of the data.

These are small problems, however. One the absolutely positive results from this project has been that we were actually able to improve our data thanks to active users. After releasing the data, train enthusiasts have pointed out several erroneous data points which would have been hard to catch otherwise. I believe these kind of results can be seen in any open data projects where closed data, previously available to a small group of people, is suddenly exposed to thousands of keen eyes.

Over the course of the project we have gotten awesome help from the users. It has been an absolute blast working with technologically adept end-users who actively give constructive feedback and point out bugs. Thanks y’all!

Cool apps for everyone!

I saved the best part for last. The whole point of the open data project was enabling developers to utilize the data in all kinds of cool applications. So far we’ve gotten apps for iOS and Android. Solita has also released an Android app. There are also several cool websites using our data. My favorite is the visual timetable at liikenne.hylly.org and my colleague likes checking the junat.dy.fi for timetables when debugging.

Hopefully we’ll see many more apps in the future! If you are looking to get started with our API, you can check out my React Train app example at GitHub.