Working with a large and long running project can be devastating. More so, if it is in production and you’re striving to maintain a good service level, while at the same time continuously shipping new features. As a side effect, you see technologies aging and you may start to worry about your professional competence in the wild.

This is a five cent guide for surviving such a situation. Do feel free to share your experiences (as a developer). My target values are:

- reliability of the shipped product, and

- mental stability of the shipper/maintainer/developer.

Image by Boogeyman13

Image by Boogeyman13

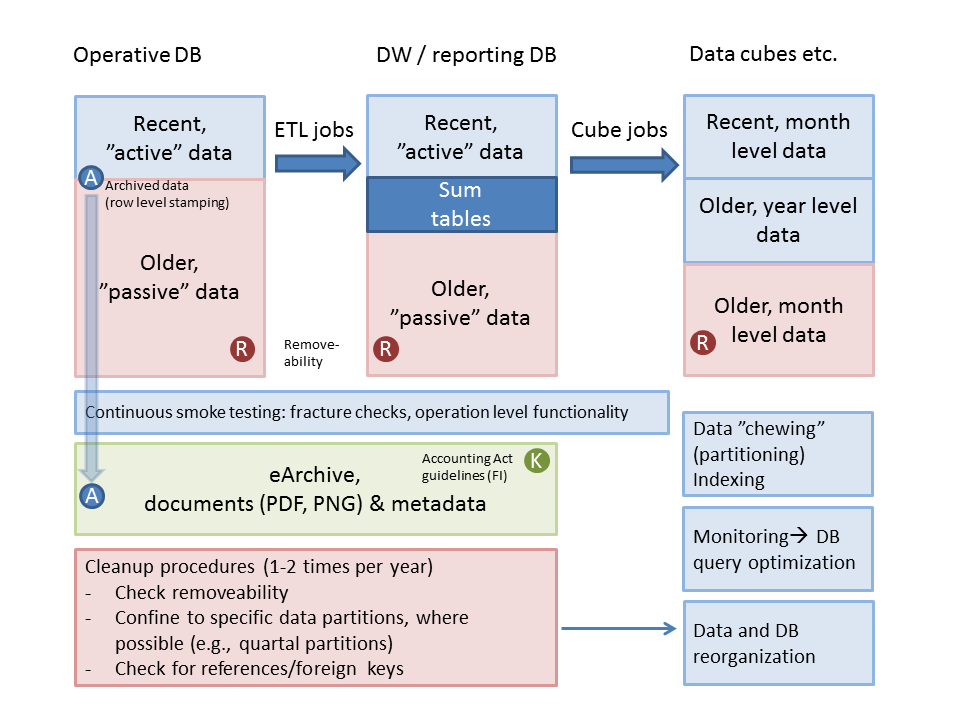

My musings base on two years with a large ERP system, now four years in production, harboring something like the following.

> 500,000 LOC (Java)

over 800 database tables within the domain model

> 700G data in the operational DB

> 1500 maintenance JIRA tickets updated (2014)

> 600 development JIRA tickets updated (2014)

over 50 timed batch jobs

some 200 integrations

14 user groups

over 4000 users

These figures indicate quite a moderate complexity of the software target. Now one interesting feature is a burden that a large system places on its developer. I have only a limited time at my disposal, and the more complex the domain gets, the greater a share of my time that goes to domain details, versus technical and technical–professional matters.

This is not a simple black/white good/bad question where domain would be icky and technology good. Business insight and data is often more valuable than code, although their realisations are limited from a developer perspective.

Here’s a recent chart drawn from our project’s data maintenance by a colleague and translated into English by me (thanks, Minna).

This is from a data maintenance perspective, on a relatively abstract level. Code, which is our main deliverable, is excluded. Yet already the number of interactions between components may seem daunting here.

##Lesson 1: How to feel bad and ask stupid questions (sometimes twice)

A big and an extensively modularised codebase can be hard to understand, and a complex ecosystem of professionals can be in some ways hard to relate to. These are normal feelings and no good grounds for suicidal thoughts…

A dev on a large system needs some cold blood, but a disciplined aproach to work helps too, to counteract complexity related anxiety. Search strategies play a central role in this puzzle.

My life is full of surprise boxes (haha)!

On an ordinary workday, one might be solving a problem like this: can I trust a source of information, or should I look for some other source to be sure? In the end, it could boil down to asking somebody’s opinion, or if one remains the prima professional, reading or debugging some code, searching for documentation or incident reports, and querying a database. Documentation is nice, but you don’t generally speaking trust it unless somebody affirms that it is trustful and up to date. Code itself can get outdated in a large system, since how a thing was implemented is neither the absolute truth nor should it be a ground de facto for business insight.

Or: what this business concept *y* would mean, and (exhaustively) what does it relate to? Now a big part of the game goes in asking, and you can tell a pro by the way they ask questions. Maintaining a good communication channel to other parties is an art in itself. Basically, feeling stupid is a good, constructive sign of personal human potential (unless you burnout, of course).

So I have this motto in progress that if one feels stupid to ask a question, it should be asked. A project group on a large system should aim to reduce communication costs, and to decrease work related anxiety.

I list here some things that seem to work in different situations. But one note first! The optimal level of communication depends on communication channel and its properties (for further details on this one, consult some classic texts on the field of communication theory 1 2).

- We prioritise and require the same from our customer

- We sit in the same space

- We use a group chat

- We have an occassional face-to-face discussion

- or meeting

- We even send group emails

- But we try to maintain office and email etiquettes

- We use several dashboards to get different views

- We create documentation with technical details as we go

- And we try to create a happy work-friendly atmosphere

- We try to remain fact centered

- We take responsibility of units of work

- We try not too talk too easily, since concentration breaks hard

- If everything else fails, one can take a break

- At our company, anyone can kick up or attend to a relevant educational session on work time

Image by Joe Haupt

Image by Joe Haupt

##Lesson 2: Track the ultimate (noise) source

In a large operative database, there may be many levels of data with respect to its originality.

When a malfunction occurs (as it sometimes will), data trackability is a key issue.

To give a complicated example, data flows from table **X** –> **Y** –> **Z**. Whereas **X** is user-maintained and transfers from **X** to **Y** could be user-initialised, transfers from **Y** to **Z** are run by a daemon relying on tables **W** and **V** for control information.

These kinds of complex transfer chains are a nightmare, in a way, but they enable time-based operations and planning-ahead of time critical business actions. (Such rules and transfer chains could be visualised on a UI to make their management easier!)

In our case, we have business critical data tables stamped with create and update times and creator and updater id’s. In this way, in theory, any recent change can be tracked and analysed. There are cases where relevant information has already been wiped out, but they are surprisingly rare. It is partly due to an architectural solution of favouring insert over update, and due to putting validity periods in control data.

Now knowing the ultimate source of a data item can help to get a kind of shortcut insight at what is going on. Data can serve as a starting point for inquiries and establish a solid background context for a logic related search task.

Here are some little starter tips.

- Communication helps

- Asking good questions from business professionals helps

- Asking what they did from end users helps

- Reading the code may help if you have sufficient background information (if your starting point is good)

-

Knowing how to search exhaustively helps a lot

(develop your search strategies!)

- Taking breaks helps

- Sleeping well is a real must

##Break 1: Take breaks and break habits

When stress starts to build up, people tend to start making stupid decisions. Stress and anxiety contribute to a weakened quality of sleep and regeneration, which will shortly build up a vicious cycle of failure.

This is why I try to speckle my “heavier” work with something unrelated, like writing a blog post – in order to give my too-hard working brain some periods of rest.

It is also a widely marked phenomenon that ideas will appear for a fresh brain; when momentarily letting go, and also in connection to regenerational activities like dreaming 3.

##Break 2: When everything else fails, draw

Many of us were told at school to tackle a problem by drawing it down in a clear manner.

(This last one is a little reminder for myself: I’m all too lazy at seizing a piece of paper, me dumbass!)

It is not costly, even when you work alone, to draw, and it will pay off both in terms of an improved clarity of thinking, and more distinct memories.

Concrete action makes for a concrete memory. Even in IT.