Programmers often reuse designs without questioning their applicability to the task at hand. A program whose design poorly matches its purpose is hard to understand, hard to test, and hard to change. Test-first development guides the design process towards better solutions by keeping it focused on the program’s purpose and highlighting design flaws that lead to poorly defined components and rigid programs.

Cargo cult programming

Cargo cult programming is a common metaphor in software development. Eric Lippert defines the concept and its origin like this:

During the Second World War, the Americans set up airstrips on various tiny islands in the Pacific. After the war was over and the Americans went home, the natives did a perfectly sensible thing – they dressed themselves up as ground traffic controllers and waved those sticks around. They mistook cause and effect – they assumed that the guys waving the sticks were the ones making the planes full of supplies appear, and that if only they could get it right, they could pull the same trick. From our perspective, we know that it’s the other way around – the guys with the sticks are there because the planes need them to land. No planes, no guys.

The cargo cultists had the unimportant surface elements right, but did not see enough of the whole picture to succeed. They understood the form but not the content. There are lots of cargo cult programmers – programmers who understand what the code does, but not how it does it. Therefore, they cannot make meaningful changes to the program. They tend to proceed by making random changes, testing, and changing again until they manage to come up with something that works.

This habit of writing code without understanding why it does what it does is a typical trait of beginning programmers. The more experience programmers have with the language and libraries used, as well as programming in general, the less likely they are to resort to cargo cult programming at the level of individual lines of source code, but that doesn’t mean they’re safe from the cargo cult mentality. They may understand what each line of code does but not be able to explain the reasoning behind their class and interface designs.

Cargo cult design

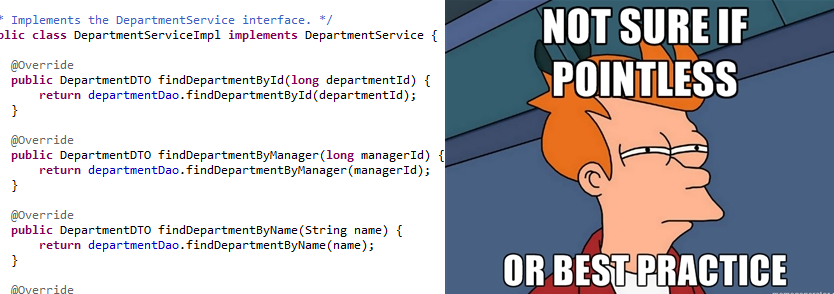

Whereas cargo cult programming is easy to spot and universally frowned upon, cargo cult design is more insidious. No-one would promote particular lines of code as the way to program something, yet designs are often elevated to the status of “best practice” and indiscriminately applied without any thought to the context or the alternatives. What’s worse, these “best practice” designs often become so ingrained in a programmer culture that any deviations from them are automatically considered bad programming. Whenever you see programmers debating whether a design is real MVC or real three-tiered architecture, you’re witnessing cargo cult mentality in action.

Programming is the art of telling another human being what one wants the computer to do. –Donald Knuth

A well-designed program makes it obvious how it fulfills its current requirements and is easy to modify when requirements change. Thus the quality of a design can only be evaluated in the context of the program’s current and future requirements. It only makes sense to write programs whose requirements differ from others’ in non-trivial ways (otherwise we’d just use or adapt an existing program), so each program’s design needs to be evaluated by unique criteria. Cargo cult design means deciding on an answer before hearing the question and holding on to that answer when the question changes. To make our programs clear, we need to start the design process from the requirements and see where they lead us.

Growing software guided by tests

There are many ways to move from the requirements to a design. Some only need a hammock. My preferred approach is usually called Test-driven or Behavior-driven development, but its spirit is best captured by the metaphor Nat Pryce and Steve Freeman coined in their book: Growing Object-Oriented Software, Guided by Tests. Growing implies a working software system that evolves incrementally instead of something that only becomes operational once built to a plan. Guided implies that tests are only a form of feedback, and coming up with a good design still requires experience, intuition, and knowledge of design principles and patterns.

I’ll demonstrate the TDD/BDD approach to software design with a minimal example. The specification is to write a browser-based “hello world” program with a twist. The program takes a person’s name as input and prints a greeting. The greetings start out cold, but become friendlier as the program keeps “meeting” the person. The friendliness level is determined per person, so the program may be friendly towards “John” but still be rude towards anyone it hasn’t met before. For the example I’ll use Java, the Spring IoC container, the Spring MVC web framework, and the Mockito mocking framework, but the approach is applicable to any language. The finished example can be found on Github.

A greeter for greeting

I start by setting up a walking skeleton: a Spring MVC controller that reads a person’s name and echoes it back. This means I have a working system with I/O capability, so I can start thinking about the application logic. The controller is an adapter whose responsibility is to connect the application to the web, so according to the single responsibility principle it’s someone else’s job to form the greeting. A natural name for that someone is a Greeter, and I’d like to call the Greeter from the controller like this:

public interface Greeter {

public String greet(String name);

}

@Controller

public class GreetingController {

@Autowired

private Greeter greeter;

@RequestMapping("/greeting/{name}")

@ResponseBody

public String greeting(@PathVariable String name) {

return greeter.greet(name);

}

}Now that I’ve specified the Greeter interface, I can forget all about its clients (in this case the controller) and focus on the implementation. Our small specification describes only one of the countless ways in which the Greeter interface could be implemented, so calling this implementation GreeterImpl is out of the question. The specified greeting strategy starts out rude but slowly becomes more cordial, so I’ll call it the SlowlyWarmingGreeter. I’ll implement this greeting strategy piece by piece, starting with the rudest greeting.

No class is an island

I decide to call the test specifying this piece of behavior shouldGreetPeopleRudelyTheFirstTime. The test’s name raises the question of how the Greeter will know how many times it has met a person. The Greeter can’t keep count of the calls to the greet method, because that would violate command/query separation. Besides, the Greeter has enough to do with the greetings, it doesn’t need another job keeping count of the people that have used the system. I don’t want to add a new parameter or method to the Greeter interface either, because the clients don’t want or need to specify the meeting counts – they just want a greeting and the rest is an implementation detail.

This leaves me with only one option: the Greeter needs a collaborator who knows how many times a person has been met. The obvious name would be a MeetingCounter, but I think of calling it a MeetingLog just in case I’ll want to store more information about the meetings than just a total count per person. I ponder this name for a while, but decide against it because the word “log” makes it sound like a write-only text file, so I finally settle on MeetingHistory, finish the first test, and watch it fail.

public interface MeetingHistory {

int timesMet(String name);

}

public class SlowlyWarmingGreeterTest {

@Mock

private MeetingHistory meetingHistory;

@InjectMocks

private SlowlyWarmingGreeter greeter;

@Test

public void shouldGreetPeopleRudelyTheFirstTime() {

// Given

given(meetingHistory.timesMet("John")).willReturn(0);

// When

String greeting = greeter.greet("John");

// Then

assertEquals("What do you want? Beat it!", greeting);

}

}He’s not that bad once you get to know him

I change SlowlyWarmingGreeter.greet to return a string literal and the first test passes. I then add a similar test for the next type of greeting and watch it fail. This time I need to add a bit of logic to the greet method to make the test pass.

public class SlowlyWarmingGreeterTest { // ...

@Test

public void shouldGreetPeopleNeutrallyAfterTheFirstTime() {

// Given

given(meetingHistory.timesMet("John")).willReturn(1);

// When

String greeting = greeter.greet("John");

// Then

assertEquals("Hello, John!", greeting);

}

}

public class SlowlyWarmingGreeter implements Greeter {

@Autowired

private MeetingHistory meetingHistory;

@Override

public String greet(String name) {

if (meetingHistory.timesMet(name) == 0) {

return "What do you want? Beat it!";

} else {

return String.format("Hello, %s!", name);

}

}

}Keeping count

Once I add a third type of greeting, SlowlyWarmingGreeter is complete and I can move on to implementing the MeetingHistory. Again, there are many valid ways in which the interface can be implemented, so naming the implementation MeetingHistoryImpl would be dishonest. To keep this example simple, I decide against using a database and will keep the MeetingHistory in memory, so I’ll call my implementation InMemoryMeetingHistory. A database-backed implementation would have to be tested with integrated tests using a real database, but InMemoryMeetingHistory is self-contained and regular unit tests will do.

The First test, InMemoryMeetingHistoryTest.shouldContainZeroMeetingsWithUnknownPeople, is easily passed by returning 0 from the timesMet method. I name the next test shouldIncreaseMeetingCountWhenPersonMet, but before I can write it, I need to decide how InMemoryMeetingHistory is notified of a person being met. A Greeter can’t notify the MeetingHistory from its greet method (it’s a query and not a command), so that leaves it up to the GreetingController.

Ignorance is bliss

The most straightforward way to proceed would be to add a notification method to the MeetingHistory interface, and add a MeetingHistory reference to the GreetingController, but I feel uneasy about it for two reasons. First, adding a command method to the MeetingHistory interface would mean that anyone with a MeetingHistory reference could change its state and thus affect the operation of every component that uses the history, which would make the system harder to reason about. Second, the GreetingController does not need the MeetingHistory to fulfill its task and I want the code to communicate this fact. I decide to add a separate MeetingListener interface that the controller can use to notify anyone who wants to know when a meeting takes place. In this case there’s only one MeetingListener, but the controller shouldn’t even know how many there are, so I’ll make it notify a collection of listeners.

public interface MeetingListener {

void personMet(String name);

}

@Controller

public class GreetingController { // ...

@Autowired(required = false)

private Collection<MeetingListener> meetingListeners = Collections.emptyList();

// ...

public String greeting(@PathVariable String name) {

String greeting = greeter.greet(name);

for (MeetingListener listener : meetingListeners) {

listener.personMet(name);

}

return greeting;

}

}Back to writing history

Now I can finish writing the test, and once I’ve seen it fail, I implement the InMemoryMeetingHistory using a HashMap.

public class InMemoryMeetingHistoryTest { // ...

@Test

public void shouldIncreaseMeetingCountWhenPersonMet() {

// When

inMemoryMeetingHistory.personMet("Bob");

// Then

assertEquals(1, inMemoryMeetingHistory.timesMet("Bob"));

}

}

@Component

public class InMemoryMeetingHistory implements MeetingHistory, MeetingListener {

private HashMap<String, Integer> meetingCount = new HashMap<String, Integer>();

@Override

public synchronized int timesMet(String name) {

Integer count = meetingCount.get(name);

return (count == null) ? 0 : count;

}

@Override

public synchronized void personMet(String name) {

Integer oldCount = meetingCount.get(name);

Integer newCount = (oldCount == null) ? 0 : oldCount + 1;

meetingCount.put(name, newCount);

}

}I run the tests, and to my surprise they fail. I’ve made an off-by-one error in the counter initialization.

Integer newCount = (oldCount == null) ? 1 : oldCount + 1;With the fix in place all the tests pass and we’re done!

Was it worth it?

The point of this exercise was to demonstrate an approach to the design process and not any particular design decision. Still, it makes sense to ask what we gained by going through all this trouble. The design I arrived at is by no means the solution to this problem – like in any creative endeavor, there’s no right answer – but it has several nice properties:

-

New greeting strategies, history storage options, and actions to be performed on a meeting can be added without modifying any existing code.

-

The classes have high cohesion and low coupling, so we can modify each aspect of the system in isolation without risk of breaking the others.

-

The tests provide us with a safety net that makes sure we don’t introduce regressions into the code we modify. They also serve as a form of documentation by providing examples of how the classes behave in different situations.

-

The classes are shielded from their collaborators’ internal complexity (I’m using that word very loosely) by simple interfaces, which only expose the aspects relevant to the client. This means we can read and understand each class without having to think about who its collaborators are and how they are implemented.

-

The system’s components are completely independent instead of being tangled up into one big operation, so we’re free to reuse them as we wish.

I hope to have convinced you that good design is highly contextual. At every step of the design process there are many questions to be asked and even more ways of answering them. This is what makes software design challenging, but it’s also what makes it creative and rewarding. Using a cookie-cutter design not only means leaving the system’s quality up to blind luck, it also means ignoring one of the most enjoyable aspects of programming.