For the Solita Code Tasting 2012 programming competition I implemented the rpi-challenger platform, which bombards the participants’ machines with challenges and checks that the answers are correct. The participants had to implement an HTTP server and deploy it on their production environment: a Raspberry Pi. The challenges were sent in the body of a POST request as newline-separated plain text. The answers were plain text as well.

For example, one of the challenges was:

+

23

94

and if the participant’s server responded with 117, the challenger accepted the answer and started sending more difficult challenges. All the challenges’ arguments were randomized to prevent hard-coding. The scoring system was designed to encourage good development practices, such as writing tests, releasing early and having high availability.

In this article I’ll first describe how the competition was devised to reach these goals. Afterward I’ll tell about my experiences of writing rpi-challenger in Clojure.

Punishing for Bad Practices

Due to the challenges being the way they were, there was barely any need for good design – a long if-else chain that switched based on the challenge’s keyword was enough. But the way of scoring the challenges was brutal against bad software development practices.

The participants in Solita Code Tasting were university students, and apparently they don’t teach good software development practices in universities – SNAFU. Most of the participants had a developmestruction environment – they were developing and testing in the production environment. In the first Code Tasting there was only one team who wrote tests for their software and deployed it only after the code was working. Thanks to the challenger’s scoring function, they won with twice as many points as the team placing second.

Developmestruction vs. The Scoring Function

The challenger’s scoring function was as follows:

The tournament consists of multiple rounds, each one minute long, and the points for each round are based on the challenge responses during that round. Challenges are sent to each participant every 10 ms and if even one request fails due to a network problem (e.g. the participant’s HTTP server is down), that’s automatically zero points for that round.

The participants’ answers to a round of challenges do not directly determine their score for the round. Instead, their answers determine the maximum score towards which their actual score slowly increases. In other words,

Points[RoundN] = min(MaximumPoints[RoundN], Points[RoundN-1] + 1)

or as it is implemented:

(def acceleration 1)

(defn points-based-on-acceleration [previous-round round]

(let [max-points (:points round)

previous-points (:points previous-round 0)]

(assoc round

:max-points max-points

:points (min max-points (+ acceleration previous-points)))))

(defn apply-point-acceleration [rounds]

(rest (reductions points-based-on-acceleration nil rounds)))

We had about ten challenges, each worth 1-35 points. If the responses to all the challenges worth n or less points are correct, then the maximum score for the round is n points. For example, if a server passes challenges worth 1, 2, 3, 5 and 6 points, but fails a challenge worth 4 points, the maximum score for the round is 3 points.

The point of this scoring function is to encourage the participants to avoid regressions and service outages. As each outage resets the current score to zero, and it takes time until the rounds’ scores recover back to the maximum, it’s imperative that the teams keep their servers functional at all times. This should drive the participants to write tests for the software, avoid doing any testing and development in the production environment, and to make suitable technology choices or use load balancing to let them upgrade their software without interrupting the service.

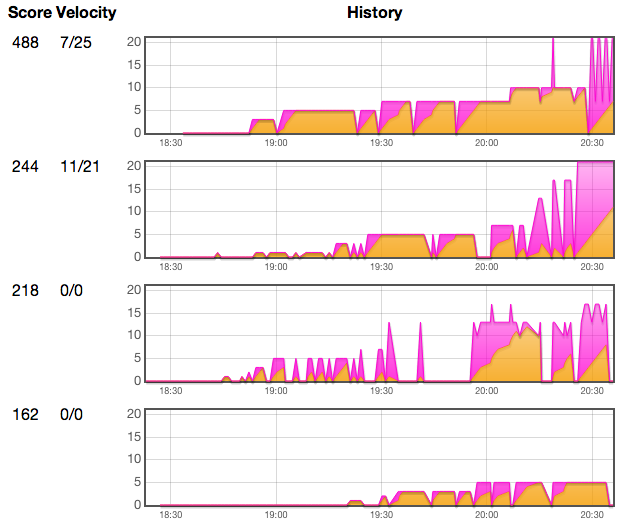

From the results it’s obvious who had a developmestruction environment and who didn’t:

The purple area in the diagrams signifies the maximum points and the orange area signifies the actual points per round. For the latest round it’s shown numerically in the velocity column.

The first team wrote tests and deployed (by restarting the server) when a feature was ready. This can be seen from the low number of service outages. The second team did all their development in the production environment and restarted their server often to see how it would respond to challenger’s requests. Even though towards the end they managed to implement more challenges than anyone else, it was too late because their service had had so little uptime.

Abandon Buggy Technologies

There was one more difference between the top 2 teams. Both of them started with the Bottle web framework for Python, and both of them were able to crash the challenger so that it would not send requests anymore to their server – it was necessary to restart challenger, but it would happen again soon. Probably there was some incompatibility between Bottle’s HTTP server and the HTTP client used by the challenger (http.async.client, which is based on Async Http Client). The problem did not occur with the other teams, who were using different HTTP servers.

The winning team quickly decided to drop Bottle and switch to some other HTTP server. The team placing second persistently kept on using Bottle, even though they had to ask the organizers many times to restart the challenger so they would start receiving points again.

This reminds me of many projects where Oracle DB, Liferay or some other technology is used (typically because the customers demanded it) even though it produces more problems than it solves…

Challenges with a Catch

There were a couple of challenges which were designed to produce regressions. This was to see who wrote tests for their software. To reveal any regressions, the challenger also keeps sending challenges that the team has already passed.

For example one of the first challenges had to do with summing two integers. Then, much later, we introduced another challenge requiring summing 0 to N integers. Since the operator (the first line of the challenge) was the same for both, there was a good chance that somebody without tests would break their old implementation.

Another sadistic challenge was calculating the Fibonacci numbers. Normally it would ask for one of the first 30 Fibonacci numbers, but there is a less than 1% probability that it will ask for a Fibonacci number that is over 9000 – that’s a big number. So that challenge required an efficient solution and also the use of big integers, or else there would be an occasional regression.

High Availability

The abovementioned scoring function punished severely for service outages. The idea was to encourage creating services which can be updated without taking the service down. Nobody appeared to have implemented such a thing, but if somebody had, they would probably have won the competition easily.

One easy solution would have been to use a technology that supports reloading the code without restarting the server (a one-liner in Clojure), but nobody appeared to have a setup like that. The participants used Python or Node.js – I don’t know about their code reloading capabilities.

Another solution, which will work with any technology and is more reliable and flexible, is to have a proxy server that routes the challenges to backend servers. That could even enable running multiple versions of backend servers simultaneously. Implementing that would have been only a dozen lines of code. Even a generic load balancer might have fared well.

Building the Challenger

Before this project I had barely used Clojure – just done some small exercises and implemented Conway’s Game of Life – so I was quite clueless as to Clojure’s idioms and how to structure the code. Getting started required learning a bunch of technologies for creating web applications (Leiningen, Ring, Compojure, Moustache, Enlive etc.) which took about one or two hours per technology of reading tutorials and documentation. When implementing the challenger, I had much more trial and error than if I had used a familiar platform. Here are some things that I learned.

Code Reloading

Clojure has rather good metaprogramming facilities. I wrote only one macro, so let’s not go there, but the reflection and code loading capabilities are worth mentioning.

The challenges that the challenger uses are stored in a separate source code repository to keep the challenges secret. I used find-clojure-sources-in-dir (from clojure.tools.namespace) and load-file to load all challenges dynamically from an external directory. The challenger reloads the challenges every minute, so it detects added or updated challenges without having to be restarted. AFAIK, that doesn’t remove functions that were removed from source code, but clojure.tools.namespace should also have some tools for doing that without having to restart the JVM.

The challenger itself also supports upgrading on-the-fly through Ring’s wrap-reload. When we had our first internal coding dojo, where we were beta testing rpi-challenger and this whole Code Tasting concept, I implemented continuous deployment with the following command line one-liner:

while true; do git fetch origin; git reset --hard origin/master; sleep 60; done

That upgraded the application on every commit without restarting the server. Also the challenges, which were in a separate Git repository, were upgraded on-the-fly using a similar command. That made it possible for some people to create more challenges (and make bug fixes to the challenger) while others were playing the role of participants trying to make those challenges pass.

Dynamic Bindings Won’t Scale

Coming from an object-oriented background, I used test doubles to test some components in isolation. I’m not familiar with all the seams enabled by the Clojure language, so I went ahead with dynamic vars and the binding function. That approach proved to be unsustainable.

I had up to 4 rebindings in some tests, so that I could write tests for higher level components without having to care about lower level details. For example, in this test I simplified the low-level “strike” rules, so that I can easier write tests for the “round” layer above it:

; dummy strikes

(defn- hit [price] {:hit true, :error false, :price price})

(defn- miss [price] {:hit false, :error false, :price price})

(defn- error [price] {:hit false, :error true, :price price})

(deftest round-test

(binding [strike/hit? :hit

strike/error? :error

strike/price :price]

...))

The problem here is that from the external interface of the system under test (the round namespace) it’s not obvious that what its dependencies are. Instead you must know its implementation and that it calls those methods in the strike namespace, and that strike/miss? is implemented as (defn miss? [strike] (not (hit? strike))) so rebinding strike/hit? is enough, and that nothing else needs to be rebound – and if the implementation changes in the future, whoever does that change will remember to update these tests and all other places which depend on that implementation.

That’s quite many assumptions for a test. It has almost all the negative sides of the service locator pattern. In future Clojure projects I’ll try to avoid binding. Instead I’ll make the dependencies explicit with dependency injection and try making the interfaces explicit using protocols (as suggested in SOLID Clojure). I will also need to look more into how to best do mocking in Clojure, in order to support GOOS-style TDD/OO.

Beware of Global Variables

You might think that since Clojure is a functional programming language, it would save you from global variables. Not automatically. Quite on the contrary, Clojure’s web frameworks seem to encourage global variables. I used Compojure and its defroutes macro relies on global state (Noir’s defpage appears the have the same problem). Any useful application has some mutable state, but since defroutes takes no user-specified parameters, it relies on that mutable state being accessible globally – for example as a (def app (ref {})), or a global database connection or configuration.

Though there are workarounds, the tutorials of those frameworks don’t teach any good practices for managing state. The only place where I found good practices being encouraged was the documentation of clojure.tools.namespace, where there is a section called No Global State, which tells you to avoid this anti-pattern (though it only glances over how to avoid it). The solution is to use dependency injection, for example like this:

(defn make-routes [app]

(routes

(GET "/" [] (the-handler-for-index-page app))

...))

This is almost the same as what the defroutes macro would produce, except that instead of the route being a global, we define it as a factory function that takes the application state as a parameter and adapts it into a web application. Now we can unit test the routing by creating a new instance of the application (possibly a test double) for each test.

Future Plans

We will probably run some internal coding dojos with rpi-challenger and do some incremental improvements to it. First of all we’ll need to improve the reliability, so that a buggy HTTP server can’t make challenger’s HTTP client fail, and solve some performance problems when saving the application state with clojure.pprint (it takes tens of seconds to write a file under 500 KB). Holding the application state in a database might also be a good idea.

In the long run, a new kind of programming competition may be desirable. Maybe something that would require more design from the competitors, for example an AI programming game (one of my first programs was a robot for the MikroBotti programming game back in 2000). A multiplayer AI remake of Battle City or Bomberman might be fun, though it remains to be seen how hard it will be to implement an AI for such a complex game in one evening.